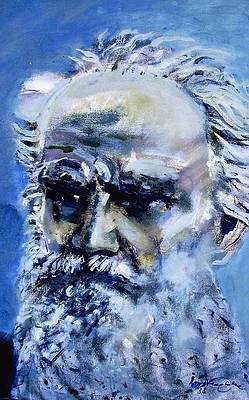

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1890

Source: From RevoltLib.com; Translated by Nathan Haskell Dole

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

In this only is the reason for the spread of all kinds of stupefying things, and among others of tobacco, perhaps the widest spread and most dangerous of them all.

It is taken for granted that tobacco enlivens and clears the mind, that, like every other habit, it allures to itself, in no case producing that effect of deadening conscience such as is caused by wine. But all it requires is to look more carefully at the conditions in which special temptation to smoke appears, in order to be convinced that the stupefaction caused by tobacco, just the same as that caused by wine, affects the conscience, and that men consciously have recourse to this form of stupefaction, especially when they need it for this object.

If tobacco merely cleared the mind and made men cheerful, then there would not be any of that terrible necessity of using it and especially in certain definite circumstances, and men would not say that they had rather give up bread than their tobacco, and they would not in reality often prefer smoking to eating.

That cook who murdered his baruinya said that, when he went into her bedroom and cut her throat, and she fell back with the death rattle, and the blood spurted out in a torrent, a panic seized him.

"I could not finish the job," he said; "I went from the bedroom into the drawing-room, sat down there, and smoked a cigarette."

Only when he had stupefied himself with tobacco, did he feel sufficiently fortified to return to the bedroom, and finish dispatching the old lady, and examine her things.

Evidently the need of smoking at that minute was induced in him, not by the desire to clear or cheer his mind, but by the necessity of drowning something which prevented him from accomplishing the deed he had planned.

Such a definite necessity of stupefying oneself by tobacco in certain very difficult moments will occur to every smoker. I remember that in the days when I smoked I used to feel the special need of tobacco. It was always at moments when I wanted not to remember what I remembered, wanted to forget, wanted not to think.

I am sitting alone, I am doing nothing, I know that I ought to begin my work, and I do not feel like it. I smoke and continue sitting idle.

I promised some one to be at his house at five o'clock and I have stayed too long. I remember that I am late but I do not want to remember it, and I smoke. I am annoyed, and I say something disagreeable to a man, and I know that I am doing wrong, and I see that I ought to stop doing so, but I feel an inclination to my bad temper—I smoke, and I continue to be angry.

I am playing cards, and I am losing more than I wanted to hazard—I smoke.

I have placed myself in an awkward position, I have done something wrong, I have made a mistake, and I must recognize my position in order to escape from it, but I do not want to do so—I blame others and smoke! I am writing and am not quite satisfied with what I am writing. I ought to throw it away, but I want to finish writing what I had in mind, and I smoke. I am discussing, and I see that my opponent and I do not understand and cannot understand each other; but I want to express my thoughts to the end, and I go on speaking, and I smoke.

The peculiarity of tobacco, distinguishing it from other stupefying things, besides the faculty which it offers for stupefying and its apparent harmlessness, includes also its portability, so to speak, the possibility of applying it to various minor occasions. To say nothing of the fact that the use of opium, wine, hashish, is coupled with certain accessories which cannot always be had, while one can always take tobacco and paper with one, and that the smoker of opium, the alcohol user, arouses horror, while the man that smokes tobacco presents nothing repulsive; the advantage of tobacco over other intoxicants is that, whereas the intoxication of opium, hashish, or wine is spread over all impressions and acts, received or produced during a sufficiently protracted period of time, the intoxication of tobacco may be directed to every separate occasion.

If you want to do what you ought not to do, you will smoke a cigarette, you will stupefy yourself just as much as is necessary in order to do what ought not to be done, and again you are fresh and can think and speak clearly; for if you feel that you have been doing what you ought not to have done, again comes the cigarette, and the disagreeable consciousness of the wrong or awkward action is done away with, and you can occupy yourself with other things and forget.

But to say nothing of the frequent occasions when every smoker betakes himself to smoking, not for a gratification of habit and a pastime, but as a means of deadening conscience for actions which have to be performed, or are already performed,—is not the strenuous definite interdependence between men's ways of life and their passion for smoking evident?

When do boys begin to smoke?

Almost always when they lose their childish innocence.

Why do smokers cease to smoke as soon as they come into more moral conditions of life, and begin to smoke as soon as they come into perverted environment. Why do gamblers almost all smoke? Why is it that the women that lead a moral life smoke least of all? Why do prostitutes and madmen all smoke?

Habit is habit, but evidently smoking is directly dependent on the need of deadening conscience, and it attains its end. How far smoking deadens the voice of conscience may be observed in the case of almost any smoker. Every smoker, yielding to his passion, either forgets or despises the very first demands of society, such as he claims from others and observes in all other circumstances, as long as his conscience is not smothered by tobacco. Every man of our average education recognizes that it is not proper, polite, or humane for one's own pleasure to disturb the comfort and happiness and still more the health of others. No one permits himself to wet a room where people are sitting, or to make a disturbance or shout, or admit a cold, hot, or fetid atmosphere, or perform actions which disturb or injure others. But out of a thousand smokers not one hesitates to puff out volumes of smoke into a room where women or children that do not smoke are breathing the atmosphere. Even if smokers are accustomed to ask of those present, "Is it disagreeable to you?"—they all know that the usual reply is, "Oh, we like it!"—notwithstanding the fact that it cannot be pleasant for one not smoking to breathe the vitiated air, and to find stinking cigar-ends in glasses, cups, and plates, on candlesticks or even in ash-trays.

But even if grown-up nonsmokers endure tobacco, at least for children, of whom no one asks permission, it cannot possibly be agreeable or advantageous. But, meantime, respectable people, humane in all the other relations of life, smoke in the presence of children, at dinners, in little rooms, vitiating the atmosphere with tobacco smoke, and not feeling the slightest pricking of conscience because they do so.

It is generally said, and I used to say, that smoking conduces to intellectual labor. And undoubtedly this is so, if one considers only the amount of intellectual labor. It seems to a man who smokes, and therefore ceases to value and weigh his thought, it seems as if many thoughts suddenly occurred to him. But it is not at all that many thoughts have occurred, but only that he has lost control of his thoughts.

When a man is working he is always conscious of two beings in himself; the one working, the other estimating the work. The stricter the estimate the slower and the better the work, and vice versa. If the one that estimates finds himself under the influence of an intoxication, then there will be more of the work, but its quality will be worse. "If I do not smoke, I cannot write. If I do not drink, I begin, but I cannot go on."

This is commonly said, and I used to say so. What does it mean? Either that you have nothing to write, or else that what you wish to write is not yet sufficiently matured in your inner consciousness, but is only confusedly beginning to present itself to you, and the estimating critic dwelling in you, not being stupefied by tobacco, tells you so. If you did not smoke you would put aside what you had begun, and await the time when what you had in mind became clear to you, you would try to think out what had dimly presented itself to you, you would consider the objections that arose, and you would direct your whole attention to clarifying your thought.

But you smoke, and the critic who has his seat within you becomes stupefied, and the obstacle in your work is removed. What seemed to you insignificant when you were unintoxicated with tobacco again acquires importance; what seemed to you obscure, no longer seems so; the obstacles rising before you are concealed, and you continue to write, and you write much and rapidly.