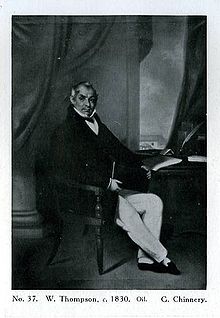

Portrait of William Thompson by George Chinnery, ca. 1830

IMR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From Irish Marxists Review, Vol. 1 No. 4, November 2012, pp. 74–80.

Copyright © Irish Marxist Review.

A PDF of this article is available here.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Portrait of William Thompson by George Chinnery, ca. 1830 |

This article is a celebration of the extraordinary life and ideas of the Cork man William Thompson.

It sets out to give a flavour of this wonderfully inspirational and original thinker who, though little known today, was a well known and influential figure in his day, especially in Britain and Europe. It will also explain why it was that when James Connolly sat down to write his most famous work, Labour and Irish history, he devoted a whole chapter to this man, who he acknowledged as being the first Irish socialist. A brief examination of Thompson’s life and achievements will leave us in no doubt as to why he earned such praise and respect from Ireland’s outstanding Marxist.

William Thompson was born in Cork in 1875. His family, from Anglo-Irish ascendancy, were one of the wealthiest in Cork and his father was Mayor of the city. His inheritance was a massive 1,400 acre estate in Rosscarbery. However, Thompson was not your run of the mill landlord. In fact throughout his whole life he protested against the wealth and power of his own class, accepting that his own life of privilege was based on the work and exploitation of other people. He was stridently anti capitalist, declaring almost 50 years before Marx that a workers have a right to the full produce of their labour. He was a vocal proponent of women’s liberation and contraception, and opposed the institutions of marriage and religion. He was an advocate of Catholic emancipation, free education, and, above all he was a resolute champion of the need for the working class to create – by its own action – a different form of society, a world where humanity would work cooperatively to enjoy the fruits of its labour, and shape its own destiny.

How can we explain this amazing story of a fabulously rich young Cork man, who, with the world at his feet, turned his back on his own social class, and became a passionate and sworn enemy of the economic system that underpinned inequality, poverty and oppression?

To begin with it is necessary to give consideration to the dynamic world that William Thompson lived in. When he was 14 years old, a political earthquake shook the social fabric of Europe to its core. The French masses succeeded in bringing about a popular revolution, ending centuries of monarch rule. This event would arouse the excitement and imagination of millions of people around the world fighting injustice. In Ireland it would inspire revolutionary upheaval, with the United Irishmen of 1798 and the Robert Emmet led rebellion in 1803. The removal of the old feudal order paved the way for a wave of enlightenment and democratic ideals. It also saw the birth of modern capitalism, which in theory held out the promise of greater freedoms and a better way of life. In particular, it ushered in an open debate around questions of Economics, democracy and philosophy. Thompson studied these topics avidly. He travelled widely as young man, his time in France earning him a reputation of a red republican (a term of abuse from his family and fellow Anglo Irish ascendancy in his native city!).

While staying with his mentor, the Utilitarian philosopher John Bentham in London, Thompson began a lifelong friendship Anna Doyle Wheeler. Wheeler was married at 15, before quickly ending her relationship with her drunken abusive husband. She worked tirelessly throughout her life for the feminist cause, and her collaboration with Thompson resulted in the most important and original analysis of women’s liberation of its time. [1] An Appeal of One Half of the Human Race, which they co-wrote 1825 in an angry response to a publication of a call from James Mill’s On Government, which called for the vote for men only.

This work immediately impresses as it describes, with great honesty, the day-to-day reality of Women’s oppression and particularly the hardships of working class women. They described what was expected of women in the following way:

An education of baby-clothes, and sounds, and postures, you are given, instead of real knowledge; the incidents are withheld from you, by which you could learn, as man does, the management of affairs and the prudential guidance of your own action

They also identified the materialist basis for this inequality in the form of competition which arises from the capitalist mode of production:

evils encompass you, inherent in the very system of labour by individual competition, even in its most free and perfect form. Men dread the competition of other men, of each other, in every line of industry. How much more will they dread your additional competition! ... How fearfully would such an influx of labour and talents into the market of competition bring down their remuneration!

They also explored the question as to whether these divisions will always arise in any society, and put forward the following hypothesis:

Not so under the system of Association, or of Labour by Mutual Co-Operation. This scheme of social arrangements is the only one which will complete and forever insure the perfect equality and entire reciprocity of happiness between women and men Large numbers of men and women cooperating together for mutual happiness, all their possessions and means of enjoyment being the equal property of all – individual property and competition for ever excluded.

They go on to identify the root of much of suffering caused to women as resting on the burden of the capitalist nuclear family structure, the removal of which could provide more freedoms:

Here no dread of being deserted by a husband with a helpless and pining family, could compel a woman to submit to the barbarities of an exclusive master. The whole Association educate and provide for the children of all: the children are independent of the exertions or the bounty of any individual parent: the whole wealth and beneficence of the community support woman against the enormous wrong of such causalities.

It is a mark of the originality and vision exhibited by Thompson and Wheeler to consider that it would take another 60 years before a more extended historical materialist account of womens oppression was published. Engels The origins of the family, private property and the state drew on anthropological research as well as Marx’s understanding of historical materialism. But Thompson and Wheelers account reaches remarkably similar conclusions.

Thompson was particularly taken with the ideas of Utilitarianism, with its motto ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ and as has been mentioned, worked closely with one of its key figures, John Bentham, and began a study of how the Economists, rationalists and moral philosophers like Bentham and Godwin might fuse together for the benefit of the human race.

An Inquiry into the Principles of the Distribution of Wealth Most Conducive to Human Happiness, Applied to the Newly Proposed System of Voluntary Equality of Wealth was published in 1825. Thompson accepts the earlier classical economic theory of Adam Smith and Ricardo, who developed the labour theory of value, which argued that the value of a commodity is related to the labour needed to produce or obtain that commodity. Smith and Ricardo, however, failed to carry this theory to its logical conclusion when it came to came analysing the usurping by the bosses of the resultant profit. Thompson, however, recognised the taking of surplus value of the capitalist as exploitation.

What, then, is the most accurate idea of capital? It is that portion of the product of labour which, whether of a permanent nature or not, is capable of being made the instrument of profit. Such seem to be the real circumstances, which mark out one portion of the products of labour as capital. On such distinctions, however, have been founded the insecurity and oppression of the productive labourer the real parent, under the guidance of knowledge, of all wealth and the enormous usurpation, over the productive forces and their fellow-creatures, of those who, under the name of capitalists, or landlords, acquired the possession of those accumulated products the yearly or permanent supply of the community.

Thompson’s views on economics were shaped by detailed study of the subject and by observing the actual evidence of the unequal distribution of wealth. He could see first hand in Cork the glaring wealth enjoyed by his own class and the deep poverty and squalor around the city. ‘Those who labour are overcome with toil, while the idle classes who live on the products of the labourer are almost equally wretched from lack of occupation.’ [2]

The implications of this were devastating for society. Instead of providing ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’, the internal dynamics of the system would ensure that

as long as the accumulated capital of society remains in one set of hands, and the productive power of creating wealth remains in another, the accumulated capital will, while the nature of man continues as at present, be made use of to counteract the natural laws of distribution, and to deprive the producers of the use of what their labour has produced.

The most galling thing for Thompson was that this arrangement was really holding society back. The increasing material advances made under capitalism made it possible to create a world where everybody could have access to food, education, health and housing. The economy could be planned democratically to meet human need. But instead of meeting these needs, the dynamics of this new system of capitalism meant that market forces were the new kings of society. This was a world, that put profit before people. He began to see that the fundamental problem of capitalism was that it separated the workers from the tools necessary to make their labour productive for human need. He states quite bluntly,

The paramount mischief of the capitalist system is that it throws into the hands of a few, the dwelling of the whole community, the raw materials on which they must labour, the machinery and tools they must use and the very soil on which they live and from which their rood must be extracted.

Thompson would devote his life to the creation of an alternative society which, for him, involved the promotion of cooperatives. He became an independent and influential theoretician within the movement developing across Europe in the 1820s – the Utopian Socialists.

One of the most famous utopian socialists was Robert Owen, a wealthy industrialist, who argued that the unrestricted competitive nature of capitalism had a severely negative impact, materially and mentally, on the human condition. He argued for co-operatives and small ‘villages of co-operation’, one of which he established in Lanarkshire in Scotland. These could create a more sustainable and harmonious environment for people to live in, through which people could improve their lives. For Owen, the co-operative movement could grow by appealing to the rich and powerful that it was in their interests to take a lower profit for the sake of social peace. The educated professionals would manage these communities. He dismissed the notion that the workers themselves could build co-operatives, and rejected the idea that class struggle could bring about improvements for workers. Owens politics, as James Connolly observed, led to some strange conclusions.

Since the new order was to be introduced by the governing class, it followed that the stronger that class became the easier would be the transition, and consequently, everything which would tend to weaken the social bond by accentuating class distinction, or impairing the feelings of reverence held by the labourer for his masters, would be a hindrance to progress. [3]

Owen was invited to speaking tours in Ireland during the famine, just when organised acts of rural violence against Landlords were becoming commonplace. Paradoxically, Owen was warmly welcomed by sections of the rich. Owen struck the right note when he suggested that ’the first step to a permanent improvement was the forbearance of all parties’. [4]

Thompson’s view of socialism was different. He rejected Owens appeal to the ruling class. He described Owens schemes of Industrial reforms as little more an ‘improved system of pauper management’, ‘He believed that a new co-operative system which would re-structure society would only be brought about by the working classes themselves.’ [5]

Thompson explicitly excluded the need for violence or forcible expropriation to take over the means of production. In his 1827 book, Labour Rewarded, he argued for the replacement of capitalism by a co-operative socialism. To bring this about he looked to the organisations of the working class as being the key to transforming society, and he identified the trade union movement as ‘by far the most important movement’ [6] of his time. He argued that the trade union movement should expand its role beyond wage negotiations and should play a leading role in setting up the co-operative movement. He was critical of those trade unions that excluded unskilled workers. Many of the Chartist leaders in Britain – Lovett, Watson, Carpenter and Bronterre O’Brien – were disciples of Thompson. [7] His book Practical Directions set out a vision of how such a co-operative might be organised. Elected committees would run the community. Management was just like any form of labour, with no special privileges.

On a personal level, Thompson was very demanding of himself. He gave up alcohol, tobacco and became a vegetarian so that he could better concentrate on his work. He reduced rents on his estate to a nominal amount and demonstrated the value of new agricultural techniques like crop rotation, to the local tenants. He devised a plan for a deep sea fishing port in Cork, and understood the need to build sustainable industries around the cooperatives. He attempted, in 1833, to turn his entire estate into a co-operative but died before his plan could be completed. His will would be contested by his relatives in a legal battle that would run for 25 years the cost of which practically wiped out the value of the estate.

How can we define Thompson’s politics? As has been mentioned, Thompson never called for revolutionary change in society. James Connolly however, provided an interesting contribution to this question, with the following insight from Labour in Irish History. Connolly recognised Thomson as a revolutionary socialist

for all the deductions from his teachings lead irresistibly to the revolutionary action of the working class. As, according to the Socialist philosophy, the political demands of the working-class movement must at all times depend upon the degree of development of the age and country in which it finds itself, it is apparent that Thompson’s theories of action were the highest possible expression of the revolutionary thought of his age. [8]

Indeed when you look at Thompson’s writings, it is difficult not to come to the same conclusion. Another passage from his book on distribution recognizes the way in which capitalists will always use the state to maintain its power:

As long as a class of mere capitalists exists, society must remain in a diseased state. Whatever plunder is saved from the hand of political power will be levied in another way, under the name of profit, by capitalists who, while capitalists, must be always lawmakers.

With regard to the merits and achievements of Thompson from a marxist perspective, Connolly argued that

the relative position of this Irish genius and of Marx are best comparable to the historical relations of the pre-Darwinian evolutionists to Darwin; as Darwin systematised all the theories of his predecessors and gave a lifetime to the accumulation of the facts required to establish his and their position, so Marx found the true line of economic thought already indicated, and brought his genius and encyclopaedic knowledge and research to place it upon an unshakable foundation. [9]

Thompson’s work was mainly ignored in Ireland until James Connolly referred to him. However, he carried some influence in Britain and in Europe in the nineteenth century and his work was read and admired by Karl Marx. In his native Cork, in the early noughties, a group of academics in Cork called ‘Praxis’ organised the interesting and varied William Thompson Weekend School which gave some overdue recognition to the county’s most original and inspiring rebel. I would also give credit to the late Cork Socialist, Jim Blake, who gave an inspired talk about the man, at the first Socialist meeting I ever attended, many years ago.

The final word on his legacy I will leave with Connolly, with his beautifully worded tribute to Ireland’s first Socialist from Labour in Irish History:

Fervent Celtic enthusiasts are fond of claiming, and the researches of our days seem to bear out the claim, that Irish missionaries were the first to rekindle the lamp of learning in Europe, and dispel the intellectual darkness following the downfall of the Roman Empire; may we not also take pride in the fact that an Irishman was the first to pierce the worse than Egyptian darkness of capitalist barbarism, and to point out to the toilers the conditions of their enslavement, and the essential pre-requisites of their emancipation?

1. Richard Pankhurst, William Thompson (1775–1833), Pioneer Socialist, London 1954, p. 5.

2. [There is no text or reference for note 2 in the printed version of the article. – Note by ETOL]

3. James Connolly, Labor in Irish History (1910), Bookmarks, p. 97

4. Fintan Lane, The Origins of Modern Irish Socialism 1881–1896, Cork University Press, 1997, p. 10.

5. Vincent Tucker and Mary Linehan, Workers’ Co-operatives – Potential and Problems, UCC Bank of Ireland Centre for Co-operative studies, 1983, p. 31.

6. Richard Pankhurst, William Thompson (1775–1833), Pioneer Socialist, London 1954, p. 118.

7. Vincent Tucker and Mary Linehan, Workers’ co-operatives – Potential and Problems, UCC Bank of Ireland Centre for Co-operative studies, 1983, p. 33.

8. James Connolly, Labor in Irish History, Bookmarks, p. 101.

9. ibid., p. 108.

IMR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 18 July 2019