ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism, No. 62, September 1973, pp. 6–7.

Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg, with thanks to Paul Blackledge.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

CERTAINLY the struggles themselves are inevitable at some point, if living standards are to be protected. For, the government’s own options as it approaches Phase Three are very limited.

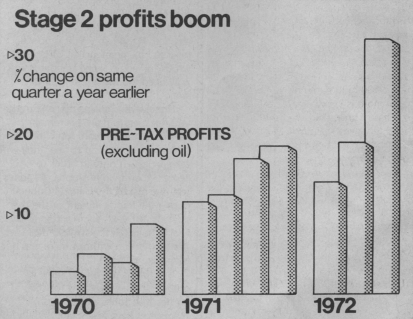

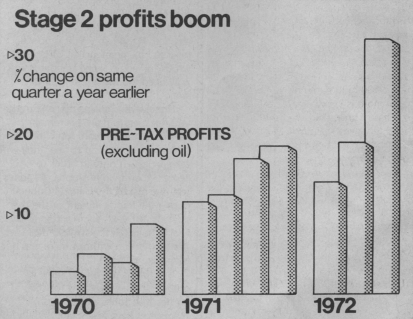

Superficially, things have gone very well for big business in the last six months. It has had its boom, with production rising by about six per cent over the last year. The policy of wage restraint has worked and profits have soared. They have risen 40 per cent in the first six months of this year, after a rise of around 17 per cent last year, and the stock exchange firm of Phillips and Drew has been able to talk of ‘an unprecedented profits boom’.

But in many industrial and financial circles the feeling is not one of elation but of pessimism. There is talk of crisis and impending doom.

In part this is because of fear that the unions may not be allowed by their rank and file to acquiesce in the freeze much longer, in the face of soaring food prices, rents and mortgage repayments. But it also reflects fear that the boom cannot be sustained, that a return to the economic Stagnation that has plagued the British economy since the mid-1960s is inevitable.

The trouble is that in-built into the boom are a number of negative factors.

The boom itself looks less impressive when seen in the context of the international economy. OECD has noted that ‘the real Gross National Products of the seven major OECD countries probably rose by 7–8 per cent during the year ending mid-1973 ... exceeding the rate achieved in any similar period since the early 1950s. For the first time since the war, in fact, the upturns in the economies of the major economies have coincided with one another.’ This is part of the explanation for the upsurge in prices internationally, as the demand for goods and raw materials has shot up everywhere.

There is considerable fear among some economists that the attempts of governments in the US, Britain, Japan and most of the Common Market to cut back on the upward pressure on prices will lead to a drop in economic growth rates in each country simultaneously, with some economists even talking of a world recession to follow the world boom.

In any case, British big business has not been doing nearly as well out of the boom as it might have hoped. The stagnation of the British economy in past years and the low level of investment in manufacturing industry is taking its toll now. Many firms just cannot fulfil the orders that are open to them. Other firms are forced to import machinery if they are to expand production. The result is that the boom has also led to a large balance of payments deficit. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) has shown that the volume of Britain’s exports is lower in comparison with the volume of its imports than in 1969. For the first time ever, car imports into Britain are greater than car exports.

|

One of the aims of the Tories when they pushed through the wages freeze last November was to hold price rises in Britain below those of its major competitors. They did succeed, for the first time in many years, in cutting the cost to employees of wages and salaries in each unit of output. But this has not held back prices.

Under the present conditions of international monetary instability, one day on the money markets can undo the work of nine months of wage freeze. The holding down of wages has increased profits. But its effect on prices has been more than compensated for by the increase in the cost of imports caused by the decline in the international value of the pound.

The Financial Times has been able to point out that rates of inflation in Britain are well above those of the US, Germany and France, although below those of Japan and Italy. Increases in the cost of basic materials for industry in July alone of more than four per cent ensure that further large price increases are on their way. The NIESR has said that inflation could reach double figures next year.

So despite the boom in sales and profits, there is doubt and uncertainty in board rooms.

Big business is still very cautious in its investment plans. It fears that the rise in profits in Phase One and Two may only be temporary, and that further increases in its costs and interest rates on borrowed money can make new large investments unprofitable. ICI and Shell, for instance, have postponed a final decision on a new £100 million ethylene cracker until more is known about the shape of Phase Three. And even the much heralded investment programme of British Leyland will still leave its spending on new machinery behind that of its major rivals such as Toyota, Nissen, Fiat, Renault and Volkswagen. The Financial Times has noted that, in the British car industry, ‘only Ford seems to be investing enough to retain its place in European markets.’

But if the government is to begin to deal with any of the long term problems of British capitalism, it has somehow to stimulate investment. And that means ensuring that profit levels in Phase Three are at least as high as those achieved in Phases One and Two.

There is considerable disagreement among the ruling class’s own economic advisors as to how serious the present situation is. Some believe that the government must bring the boom to an end now if prices are not to shoot through the ceiling. Others believe tax increases or cuts in public expenditure can keep the economy expanding without prices getting out of hand. And a few believe that everything is going all right as it is.

But one thread of unanimity does run through their divergent positions: the easiest way for the government to begin to deal with its problems is to hit workers’ living standards in the next 12 months as hard as it has in the last nine.

The London and Cambridge Economic Bulletin has asserted that ‘it is inevitable that the growth in consumption should slow down compared with the past two years ... We are bound to go through a period in which it grows much slower than the national income ... The sooner that is explained to the public the better.’

The House of Commons expenditure committee has come to similar conclusions – that it is likely that ‘real personal disposable income would show no growth before the second quarter of next year.’

The most optimistic prognosis, from the government’s point of view, has come from the NIESR. But it too urges the government to be harsher in Phase Three than in Phase Two. ‘There is,’ it says, ‘a strong case for having as low a money rise as possible built into Phase Three’ and suggests a norm of seven per cent – less than the Phase Two figure which totalled about eight per cent. At a time when prices are, according to official calculations, up 9.5 per cent on last year, it is talking about cuts in real wages for most workers.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 1 March 2015