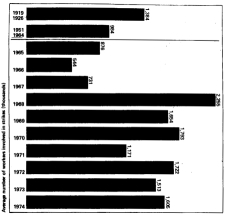

Average no.of workers involved

in strikes (000s)

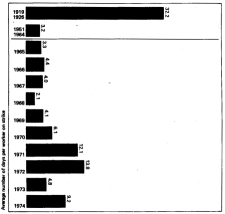

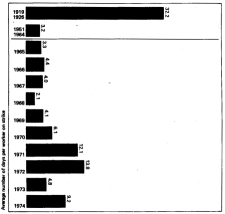

Average no. of days per worker on strike

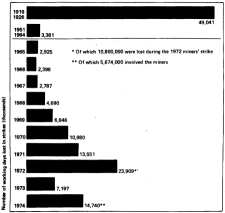

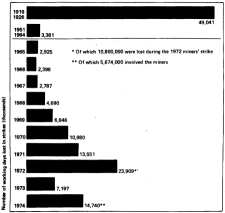

No. of working days lost in strikes (000s)

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism, No.76, March 1975, pp.7-15.

Transcribed & marked up by by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

FROM THE factory-by-factory, ‘do-it-yourself’ reformism of the 1950s and 1960s something new is emerging. Two main theories attempt to explain and guide it. One theory argues that the deepening crisis is strengthening the ‘left trend’ in the labour movement, and as this happens workers will turn more and more to the left leaders in the trade unions and in Parliament for socialist policies. The other, held principally by the International Socialists, suggests that as the crisis steadily worsens, the left reformist path will become an increasingly blind and occasionally bloody alley, and that workers must attempt to forge strong defensive rank-and-file organisations now. These organisations will challenge the reformist leaders for control of the trade unions while trying to keep the strength to act independently. These rank-and-file organisations linked together in a national movement will act primarily in defence of workers’ interests. But untrammelled by a reformist bureaucracy they will also be capable of challenging capitalism itself.

How do these two theories stand up in particular to the experience of the last five years?

AS LONG ago as 1881 Engels pointed to the contradictory character of the trade unions. On the one hand they certainly helped ‘the organisation of the working class as a class’ and by uniting workers they could win ‘at least the full value of the working power which they hire to their employer’ and even regulate ‘with the help of State laws, the hours of labour’. But on the other hand, he wrote, ‘It is well known that not only have they not done so, but that they have never tried’ to free ‘the working class from the bondage in which capital – the product of its own hands – holds it.’ The trade unions operated within the system, enforcing its laws, while in order to change the system a ‘political organisation of the working class as a whole’ was needed.

The temporary collapse of the possibility of building such a mass revolutionary party with the defeat of the 1926 General Strike, and the evolution of the Communist Party away from revolutionary politics, meant that the trade unions continued to develop under British capitalism for the last 50 years with the ‘naturally restricted horizons’ Rosa Luxemburg pointed to as an important source of bureaucratic, reformism:

‘The specialisation of professional activity as trade union leaders, as well as the naturally restricted horizon which is bound up with disconnected economic struggles in a peaceful period, leads only too easily, amongst trade union officials, to bureaucratism and a certain narrowness of outlook ...

‘There is first of all the overvaluation of the organisation, which from a means has gradually been changed into an end in itself, a previous thing, to which the interests of the struggles should be subordinated. From this also comes that openly admitted need for peace which shrinks from great risks and presumed dangers to the stability of the trade unions, and further, the over-valuation of the trade union method of struggle itself, its prospects and its successes ...

‘From the whole Social Democratic (Marxist – SJ) truth which, while emphasising the importance of the present work and its absolute necessity, attached the chief importance to the criticism and the limits to this work, the half trade union truth is taken which emphasises only the positive side of the daily struggle.

‘And finally, from the concealment of the objective limits drawn by the bourgeois social order to the trade union struggle, there arises a hostility to every theoretical criticism which refers to these limits in connection with the ultimate aims of the labour movement.’

Thus, as both Engels and Luxemburg saw, an understanding of the limits of trade union action and of the connection between different aspects of the class struggle is essential, not only if the limits are to be challenged, but also for the most effective struggle within capitalism to be waged as well.

IN 1972 and 1974 the left leadership of the AUEW, for example, defended its refusal to campaign for national strike action on the grounds that it could bankrupt the union. Instead it launched campaigns of ‘guerrilla’ strike action and overtime bans that were destined to failure from the start. Paradoxically, their commitment to the union as an end in itself meant that when the union’s funds were seized by the Industrial Relations Court in May 1974, they did call the action they had previously argued was out of the question and score a major victory.

As rank-and-file action has increased, the reaction by the left union leaders, far from encouraging and sustaining it, has been to limit it as much as possible and to put the interests of ‘their’ union first. Thus Hugh Scanlon and Jack Jones instructed their Chrysler Linwood members to work with blacklegs in September 1973. And in November 1974 the AUEW executive instructed AUEW members of the Head Office staff to scab on striking APEX clerical workers or face expulsion. The ready acceptance of the limits laid down by the Labour government explain other notable AUEW decisions of 1974: the EC instructions to their Dundee Timex members to return to work and accept a Phase 3 deal (March 1974) and to their Lanarkshire Hoover members to return to work and stop rocking the Social Contract (November 1974); Hugh Scanlon’s refusal to carry national policy and vote against the Social Contract at the September 1974 TUC and so on.

Other factors are, however, also at work shaping the trade union bureaucracy so that its first loyalty is to itself and the permanence of its relationship with the state and the employers rather than to the rank-and-file. As far back as 1920 the Fabians Beatrice and Sidney Webb commented that,

‘The paramount necessity of efficient administration has cooperated with this permanence (of their job) in producing a progressive differentiation of an official governing class, more and more marked off by character, training and duties from the bulk of the members.’

Today we can add ‘more and more marked off by wages, working conditions and aspirations as well. Only last November full-time officials’ wages in the AUEW, where tradition has kept them much closer to those of their members (and hence lower) than in other unions, were increased as follows: for the President and General Secretary from £3750 to £5250, for EC members to £4550 and for local officials to £3850. And in virtually every union full-time officials have access to cheap mortgages, generous expenses for the frequent overnight business away from home and a union car (in the AUEW a new Vauxhall every year) complete with mileage allowance.

Given wages and condkions so markedly better than those of the rank-and-file it’s only natural that full-time officials begin looking upon themselves as a cut above the rest. ‘Most full-time officials rate themselves among the holders of middle-class posts (and rate their general secretaries close to the top of a scale of social standing)’, a 1961 survey reported. The same study showed that the trade union bureaucracy hardly ever contemplates going back to the rank-and-file. Mark Young, EETPTU National Officer and former right-wing collaborator with Frank Chapple, at first announced his intention to ‘go back to the tools’ when Chapple sacked him. But at the very moment when some Communist Party EETPTU members began to argue that he had a better chance of defeating Chapple than a rank-and-file candidate, it became known that Young had accepted a rather higher-paid job – as General Secretary of BALPA.

Elections have become, however, an increasing rarity among British trade union officials. Most have some kind of elected lay executive that is formally in charge but in reality can in no way control the activities of the appointed officials. A few have an election – for life – for the General Secretary. The AUEW has regular elections every three or five years for all its officials, until the age of 56, that is, when if they get home again they’re in until retiring age.

Electoral accountability – real or imaginary – has been reduced through pressure from a variety of sources. Amalgamation has afforded the bureaucracies many opportunities in recent years to cut away the ‘wasteful’ and ‘unnecessary’ rights of the members. The post-war decline of the trade union branch meeting, particularly in the manual unions and where branches are not based on the place of work, has also played its part. The shop stewards, who are still normally regularly elected and recallable by their members, have been kept at a distance from the official union structure. The check-off system of paying union dues, a practice finally adopted even by the AUEW in 1970, has helped maintain this. And as the branches become increasingly distanced from the real life of the union then the argument that complete control should rest with the branches becomes harder to carry.

|

Britain’s Major Trade Unions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Members |

Full-time |

Seats on TUC |

Accountability |

|

AUEW |

1,150,000 |

200 |

3 |

3 or 5-yearly elections |

|

ASTMS |

130,000 |

32 |

1 |

Appointed by lay Executive |

|

EETPTU |

420,000 |

150 |

1 |

Appointed by full-time |

|

GMWU |

800,000 |

? |

2 |

All candidates for officials |

|

NALGO |

541,518 |

250 |

2 |

All officials appointed |

|

NUM |

284,153 |

? |

2 |

Elected for life |

|

NUPE |

491,000 |

111 |

1 |

Appointed by lay Executive |

|

NUR |

180,000 |

49 |

1 |

|

|

NUT |

|

1 |

Appointed by lay Executive |

|

|

TGWU |

1,818,000 |

? |

4 |

Appointed by lay EC except |

|

UCATT |

|

2 |

|

|

|

UPW |

198,000 |

? |

1 |

|

|

USDAW |

350,000 |

135 |

1 |

|

|

|

22* |

|||

|

* There are 40 seats on the TUC General Council |

||||

|

? The trade union concerned is not prepared to disclose this detail over the telephone. |

||||

The increasing strength of the left from the mid-1960s within many unions where appointments are formally controlled by a lay executive, as in the TGWU and TASS, has also contributed to an erosion of democracy. The strongest force in that left, the Communist’Party, has been attracted to the possibilities of changing the political complexion of a union through appointing left officials without having to campaign for their election within the rank-and-file. The vision of this seductive short-cut means that in several unions Communist Party members now openly oppose calls for regular elections of all full-time officials as ‘ultra-left’. In TASS last year, for example, General Secretary Ken Gill (an appointed position) the only Communist Party member on the General Council of the TUC, himself appointed a leading Communist Party member as TASS women’s organiser on the staff despite the fact that she had no experience of office in TASS and had previously been an ATTI lecturer.

ON EVERY side the pressure mounts. The limits of trade union reformism, and the blind refusal to recognise them; the distinct social conditions of full-time officials; the absence of any real accountability to the rank-and-file. All these operate to separate them as a caste from the workers. The trade union bureaucracy is not part of the working class, but nor can it be identified with the employers. In 1969 Tony Cliff described the perspectives for the period we have just been through as follows:

‘The vacillation of the trade union bureaucracy between the state, employers and the workers, with splits in the far-from-homogenous bureaucracy will continue and become more accentuated during the coming period. The union bureaucracy is both reformist and cowardly. Hence its ridiculously impotent and wretched position. It dreams of reforms but fears to settle accounts in real earnest with the state (which not only refuses to grant reforms, but even withdraws those already granted) and it also fears the rank-and-file struggle which alone can deliver reforms. The union bureaucrats are afraid of losing what popular support they still maintain but are more afraid of losing their own privileges vis-à-vis the rank and file. Their fear of the mass struggle is much greater than their abhorrence of state control of the unions. At all decisive moments the union bureaucracy is bound to side with the state, but in the meantime it vacillates.’

The Communist Party, among others, has disputed the suggestion that there is a trade union bureaucracy which can vacillate in this way. In an article last November called The myth of rank and filism in the Communist Party fortnightly review Comment, Jon Bloomfield wrote of the IS analysis of the non-working class character of the bureaucracy:

‘This sociological division is in sharp contrast to the Communist Party’s political analysis of the main trends within the Labour movement; that is between a right wing, reformist trend, anxious to avoid conflict and willing to collaborate with employers and government, and a left trend, containing within it reformist and revolutionary elements – but willing to fight for policies in workers’ interests and which challenge right wing domination of the labour movement.’

This glib critique will not, however, do. It doesn’t, naturally enough, even attempt a class analysis of its own of the bureaucracy, and the whole burden of its argument is the assertion that there exists ‘a left trend’ including left reformists ‘willing to fight for policies in workers’ interests’. As long as this is never put to the test then it retains credibility. But when the pull of the state machine on the bureaucracy gets bigger, with, for example, the return of a Labour government including Tribunite Michael Foot as Minister of Employment, then what Bert Ramelson’s pamphlet Social Contract: cure-all or con-trick? describes as ‘mistakes on left’ start to recur too often to be avoided. Ramelson laments:

‘With a few honourable exceptions, most of the left trade union leaders, who played a key role in convincing the TUC to reject unconditionally all forms of “incomes policy”, are amongst the foremost champions of the Social Contract.’

The Communist Party’s national industrial organiser goes on,

‘I do not question the sincerity and genuineness of these left leaders ... But it is not honest intentions that matter in politics; it’s the consequences of policies that determine the pattern of political developments.’

The only viable means of bringing the vacillating left bureaucrats back to outright rejection of all forms of wage restraint and keeping them there is by building strong rank-and-file organisations within their unions that would act independently and throw them out if they broke ranks. But what conclusion does Ramelson draw?

‘That is why it is so essential to develop the dialogue in an effort to convince them that they are mistaken.’

he writes. The Communist Party offers no explanations as to the source of the errors, no analysis of the nature of the bureaucracy, both left and right, and hence can only suggest their ‘mistakes’ come from muddle-headed thinking.

THE IMPORTANCE of the interaction of the rank and file with the vacillating trade union bureaucracy must not be underestimated. Precisely because the state places great store by the trade union leaders, millions of workers turn first for leadership to them. Further, the contradictory character of their position means that occasionally they can be pushed into supporting working class actions such as the 1 May 1973 Day of Action and the 14 January 1975 Lobby of Parliament that they would clearly prefer to have avoided. We should note very carefully the formulations of the relationship between rank and file and the bureaucracy that were made in that earlier decade of revolutionary potential and organisation from 1915.

The Clyde Workers’ Committee produced the classical definition,

‘We will support the officials just so long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them.’

With the return of mass unemployment after the 1914-18 war and the employers’ successful attack on shop organisation, the National Administrative Committee of the Shop Stewards’ and Workers’ Committee Movement that had been established called for ‘active propaganda inside the trade unions and ... fuller participation in the internal work of those organisations.’ Later in 1920 it recognised the significance of the newly-formed Communist Party and decided that

‘The SS and WCM and the Communist Party should devise some convenient arrangement to ensure the perfect harmony of the two organisations.’

Willie Gallagher, an EC member of the Communist Party and Secretary of the Red International of Labour Unions in Britain, was instructed from mid-1923 to prepare the ground for a national movement. A number of militant centres in different industries had already developed under the name of Minority Movements, and his job was to pull them together. This was done first among the Miners and later the idea was spread to the transport workers, to engineers, to builders and to vehicle builders. In each case programmes of demands on wages and conditions and for union democracy and workers’ control were adopted. The first major success came early in 1924 when A.J. Cook was elected on the Miners’ Minority Movement programme as Secretary of the Miners’ Federation. At the Sixth Congress of the Communist Party in May 1924, Harry Pollitt moved the resolution that called for the building of the National Minority Movement:

‘The Communist Party welcomes these Minority Movements as the sign dfthe awakening of the workers. The Communist Party will throw itself wholeheartedly into the struggle of the Minority Movements and will do all in its power to assist them in their struggles.

‘The Communist Party, however, declares unhesitatingly to all the workers that the various minority movements cannot realise their full power so long as they remain sectional, separate and limited in their scope and character. The many streams of the rising forces of the workers must be gathered together in one powerful mass movement ...’

Three months later the first NMM Conference was held with some 270 delegates attending. The largest group of delegates were miners, but there were also 48 AEU members (3 from District Committees), 14 from the Municipal Workers, 13 from the TGWU, 12 from the NUR and 33 from Trades Councils.

The Manifesto adopted at the Conference began by contrasting the growth of rank and file struggle shown in repeated unofficial strikes with ‘the increasing stagnation and decay of the old leadership’. It further made clear:

‘We are not out to disrupt the unions, or to encourage any new unions. Our sole object is to unite the workers in the factories by the formation of factory committees; to work for the formation of one union for each industry; to strengthen the local Trades Councils so that they shall be representative of every phase of the working-class movement, with its roots firmly embedded in the factories of each locality.

‘We stand for the formation of a real General Council that shall have the power to direct, unite and co-ordinate all struggles and activities of the trade unions, and so make it possible to end the present chaos and go forward in a united attack in order to secure, not only our immediate demands, but win complete workers’ control of industry.’

The two-day Conference ended with the election of an EC of 15 from the different sections present. A majority of these were Communist Party members, including three Central Committee members, Harry Pollitt, Arthur Homer and Wal Hannington. In turn the EC elected Pollitt as Secretary and Tom Mann, the former General Secretary of the AEU, was co-opted to the prestigious position of President.

This survey is not the place to retell the full history of the first shop stewards’ movement or the National Minority Movement, but some points must be made. Both became national movements during periods of close collaboration between the trade union bureaucracy and the state. The first during the First World War and the second during the first Labour government. They were based on several pockets of existing militancy and rank and file groups whose members wanted to co-ordinate centrally to cement existing links and expand into new areas. Both steered firmly away from calls for revolutionary breakaway unions and called for systematic work within the existing trade union machine while recognising that workshop organisation and factory committees held the key to the future. In both the organisational drive came from revolutionary socialist parties; in the case of the NMM entirely from the Communist Party whose militants openly fought for leading positions within it while simultaneously defending its institutional independence.

If the objective conditions are now ripe for the transition from rank and file activity to rank and file organisation and a national movement, then we can learn certain tactical lessons from this experience:

It is to the objective conditions that we now turn.

THE VACILLATIONS of the trade union bureaucracy and the development of the rank and file movement have always been important to socialists, but in this present period they have moved to occupy the centre of our political attention. In our period parliament has become less and less the directing centre of the British capitalist state and less and less the arena for the struggle for working class reforms.

Until the 1950s, parliament and first the Liberal Party (pre-First World War) and then the Labour Party were looked to as being the place and the organisations which could win real gains for the working class within the capitalist system. For example in the face of the 1901 Taff Vale court decision which threatened to make trade unipn funds liable for losses and damages incurred by firms during strikes, the labour movement concentrated on getting enough Labour representatives into parliament, and putting enough pressure on Liberal MPs, to change the law. The 1906 Trades Disputes Act which guaranteed trade union funds was a result of the election of 40 Labour MPs and the re-election of a Liberal government. Yet no-one believed from 1969-1974 that the answer to Labour’s In Place of Strife or the Tory Industrial Relations Act was 40 Communist MPs.

With the decline of British capitalism, parliamentary sovereignty counts for less and less. Richard Crossman’s diary records the way the decision was taken to postpone increases for old age pensioners in 1964 and shows the power of the giant multi-national companies and international finance. And with full employment in the 1950s and 1960s, a stronger shop floor trade union organisation and a more self-confident working class emerged. It was shop floor ‘do-it-yourself’ reformism that won concessions through collective bargaining and not parliamentary legislation. Company pensions, sick-pay, holiday pay, lay-off pay, bereavement absence pay, maternity rights, longer holidays and a shorter working week have all been negotiated. Whilst the ‘welfare state’ was being eroded by successive Tory and Labour governments from the 1950s on, employers were frequently forced to pay out, not only wages, but also many social welfare provisions directly to the workers without the intervention of parliament or a reformist political party.

In short, the struggle for ‘reforms’ shifted from parliament to the trade unions. The Labour Party reflected this shift by emerging just before the 1964 General Election as a parliamentary party committed not to ‘reforms’ but ‘rationalisation’. From 1964-70 it became openly a ‘progressive capitalist’ government with the object of weakening working class organisation in the interests of Capitalism and Investment. Within it there remained a handful of reformist socialists, anxious about the anti-trade union proposals, the doubling of unemployment, its incomes policies and the attacks on the welfare state. But for the vast mass of the Labour movement the answer was to turn from parliamentary action to political strikes. Work inside the constituency Labour Parties was rejected for direct action against the governments of the last five.years, as this list of political strikes shows:

|

1969-1974 POLITICAL STRIKES |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Approx. |

Major Areas |

Issue |

|

Feb. 27 1969 |

150,000 |

Scotland/Merseyside |

In Place of Strife |

|

May 1 1969 |

250,000 |

National |

In Place of Strife |

|

Dec. 8 1970 |

600,000 |

National; London, |

Industrial Relations Bill |

|

Jan. 1 1971 |

50,000 |

Midlands |

Industrial Relations Bill |

|

Jan. 12 1971 |

180,000 |

Merseyside, Scotland, |

Industrial Relations Bill |

|

Sunday 21 Feb. 1971 |

250,000 |

London Demonstration |

Industrial Relations Bill |

|

March 1 1971 |

1,500,000 |

National; AUEW |

Industrial Relations Bill |

|

March 12 1971 |

1,500,000 |

National; AUEW |

Industrial Relations Bill |

|

June 23 1971 |

100,000 |

Clydeside |

UCS & Unemployment |

|

Aug. 18 1971 |

150,000 |

Scotland |

UCS & Unemployment |

|

Nov. 24 1971 |

85,000 |

S & NW London |

Unemployment |

|

July 24/26 1972 |

250,000 |

National; dockers, Teesside, |

Free the Five vs. NIRC |

|

Sept. 1973 |

8,000 |

Scunthorpe |

Old Age Pensions |

|

Dec. 18 1972 |

55,000 |

London, Oxford, |

Against NIRC fine |

|

Dec. 20 1972 |

170,000 |

National, engineers |

Against NIRC fine |

|

May 1 1973 |

2,000,000 |

National; 250,000 |

Against Phase 2 & |

|

Nov. 5, 12, 19 |

|

National; engineering, |

Against Con-Mech fine |

|

Dec. 1973 |

2,000 |

Birmingham building |

Against trial of 5 |

|

Dec. 20/21 1973 |

2,000 |

National; building |

Jailing of Shrewsbury 3 |

|

Jan. 15 1974 |

10,000 |

National; building |

Jailing of Shrewsbury 3 |

|

May 8 1974 |

500,000 |

National; official |

Against NIRC seizure |

|

June/July 1974 |

10,000 |

National; stoppages by |

Support for nurses |

|

Average no.of workers involved |

|---|

|

|

Average no. of days per worker on strike |

|

|

No. of working days lost in strikes (000s) |

|

No socialist trade unionist today seriously argues for leaving it to the MPs to free the Shrewsbury pickets, prevent factory closures and short-time working or to stop inflation.

THIS SAME five year period has also seen a dramatic increase in all the main indices of strike action. The graphs opposite compares the militant years, 1919-1926, with the ‘never had it so good years’ from 1951-64 and the record of the last ten years.

The official statistics miss out strikes that last for less than a day and all the political strikes listed above, so they don’t give us the whole picture. But what we do know is that as strikes have got longer and as harassment from the Social Security has got worse, then so strikers’ tactics have got harder too. Factory occupations, the use of mass and flying pickets and the appeal for ‘blacking’ have become nearly commonplace. These tactics depend for their ultimate effectiveness much more heavily upon the response from other trade unionists than was the case in the 1950s and 1960s when the act of stopping production itself was the most effective weapon that workers had. Then, picket lines were often non-existent or completely passive. Now a new militancy has returned. This is also reflected in the increased attention being paid by strike committees to appeal sheets and factory collections. Whilst economic struggles were still largely fragmented in 1974 the workers involved increasingly raised their sights on what the rest of the movement could do for them.

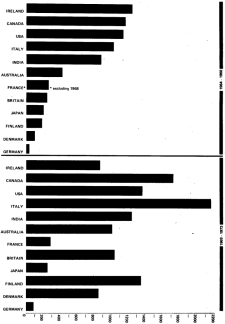

Further, this hardening of the class struggle is not confined to Britain. The international character of both the ruling class attack and the working class response during the last five years of deepening capitalist crisis is shown clearly in the graph below, which contrasts the British strike statistics with those of the other major capitalist countries.

Every important capitalist country except Ireland (where a major anti-imperialist struggle has been taking place) has shown a dramatic jump in strike activity.

|

Average no. of working days lost |

|---|

|

THIS SIGNIFICANT increase in rank and file activity has two other important features that mustn’t be overlooked. Firstly, not only has trade union membership continued to rise from 8,725,000 in 1968 to 10,001,000 in 1974, but shop and office organisation has developed even more dramatically. In 1968 the researchers for the Donovan Royal Commission on the Trade Unions estimated that there were some 175,000 shop stewards in British industry. But by mid-1974 the government’s Office of Manpower Economics put this figure at 300,000. Even after making enormous allowances for the ‘guesstimate’ nature of these figures we are still left with a reality of strengthening shop and office floor trade unionism. The impact of the successful miners’ strike and the defence of the jailed dockers in 1972 on the consciousness of wide sections of workers cannot be underestimated.

The pressure to strengthen rank and file organisation has been felt at a whole number of levels. After the sell-out of 1969, the domination of full-time officials on the Ford National Joint Negotiating Committee has now been nearly entirely reversed in favour of factory convenors. In 1971 it was the UCS shop stewards who led the national campaign to prevent wholesale sackings on the Upper Clyde. In 1972 the first tentative steps were taken to rebuild a Chrysler combine since Rootes smashed the earlier one ten years before. In 1973 attempts were made to establish combine organisations in GEC and among the UK operations of the giant multinational ITT. In September 1974 workers from 11 Lucas factories met in Birmingham to take the first steps to build a combine organisation within the Lucas electrical division. The Chairman’s opening remarks were reported in the official minute as follows:

‘The meeting had been organised by the BW3 Joint Shop Stewards Committee because it was felt that while it was possible to win sectional issues, individual factories in the Lucas group were in no position to put up any fight on main issues such as wage claims and redundancies. The last few years have seen a decline in living standards, and in the present period of high inflation there was the threat of an even larger fall in living standards and mass unemployment. Unless a proper organisation existed in the Electrical Combine, such as already existed in the Aerospace Combine, there was little chance of any fight back on these issues.’

The realisation of the difficulties of ‘going it alone’ and the observation of what other workers were doing provided the trigger for rank and file organisation.

The effect of the pressure to, strengthen rank and file organisation has spread far beyond these traditionally well-organised workers in the motor, engineering and ship-building industries. From the beginning of 1974 shop stewards from the various Shell sites around the country began meeting regularly, laying the groundwork for the militancy which led to their pioneering attack on the Social Contract in June. Ernie Twigg, the senior TGWU shop steward at Stanlow, said after the dispute ended in July:

‘We could have beaten the economic power of Shell with the support of the other locations. The role of the full-time officials made it impossible to get this support. This could have been a great victory. The reason it wasn’t isn’t lack of fight in the rank and file, but the antics of full-time officials at national level.’

Hamstrung as they were by the TGWU bureaucracy, the rank and file fought and won their second wage agreement in six months, and petro-chemical workers everywhere gained in confidence and militancy.

Unofficial, rank and file meetings of shop stewards also preceded the autumn 1974 strikes of Scottish lorry drivers, bus drivers and of BRS workers, and played a vital part in giving the stewards the confidence to lead their largely inexperienced workers into action. With the bakery workers an unofficial shop stewards’ meeting took place in December at the end of the official strike. Women and Asian workers are two other ‘newer’ sections that increasingly took the lesson of 1974 to heart: ‘Organise, take strike action and watch the trade union officials’. Early in 1975 textile and chemical workers at Courtaulds have taken their first steps towards building a rank and file combine.

The second feature of the rise in militancy that is of considerable significance is that in 1973 and especially in 1974, white collar workers moved into action on an unprecedented scale. One-day protest strikes were followed by lengthy sectional overtime bans in the CPSA, the main civil service union. NALGO launched its first all-out strikes and smaller guerrilla actions among London local authority workers. Even nurses moved into action forming Nurses’ Action Committees and actually taking strike action.

Half and one-day token strikes among London teachers were not new. But what was new was that most of them were unofficial, as was the development later in 1974 of mass unofficial action among Scottish teachers. The most encouraging sign was that not only did these white collar workers move into action, usually against the direct wishes of their trade union leaders, but they also realised the importance of on the job representation. NALGO sectional ‘shop stewards’ and school ‘delegates’ have been seen in action to be the best forms of rank and file organisation with which to challenge the employer and beat off the union bureaucracy.

THE EFFECTIVENESS of working class reformism depends on the balance of class forces at any one time. While ruling class confidence and the might of the multinationals and the state machine can be assumed to be relatively constant, our side of the balance isn’t. The trade union bureaucracy tends always to side with the state and the employers but under a Labour government it does so as a matter of course. This is because it accepts the definitions of the limits of its field of action much more readily from the progressive capitalist reformists of the Labour Party, with whom it has close institutional links, than from the Tory Party.

The following tables indicate the rapidity of the turnabout of the trade union bureaucracy’s attitude to the rank and file when Labour comes to power:

|

From Labour to Tory and Back Again |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of |

No. of strikes |

% of total strikes |

|

|

1965 |

1,496 |

97 |

4.1 |

|

1966 |

1,937 |

60 |

3.1 |

|

1967 |

2,116 |

108 |

5.1 |

|

1968 |

2,350 |

91 |

3.8 |

|

1969 |

3,116 |

98 |

3.1 |

|

1970 |

3,906 |

162 |

4.1 |

|

1971 |

2,228 |

161 |

7.2 |

|

1972 |

2,497 |

160 |

6.4 |

|

1973 |

2,873 |

132 |

4.6 |

|

1974 |

2,882 |

96* |

3.0* |

|

* = Provisional |

|||

|

|

% of strikers |

% of days lost |

|

1969 |

17.1 |

23.6 |

|

Jan.-June 1970 |

15.2 |

17.3 |

|

July-Dec. 1970 |

18.0 |

41.5 |

|

1971 |

32.1 |

74.2 |

|

1972 |

36.9 |

76.2 |

|

1973 |

26.2 |

27.9 |

|

Jan.-Feb. 1974 |

79.2 |

88.1 |

|

May-Dec. 1974 |

10.5* |

11.5* |

|

* = Provisional |

||

Active trade unionists didn’t need to hear Jack Jones warn his Scottish TGWU members in Motherwell last October that they should not demand too much from their employers. Nor did they need to read his appeal for ‘equality of sacrifice’ in the February 1975 issue of the TGWU Record. They know that the trade union bureaucracy, both left and right, is implementing its agreement with the Labour government not to use the official trade union machine to prevent falling living standards.

The last year of Labour government and deepening crisis has therefore seen the rising tide of rank and file action come increasingly into conflict with the vacillating King Canute of the trade union bureaucracy. The result has been a sharpening of political confrontation within the trade union movement, the partial strengthening of rank and file organisation, and the creation of good conditions for the development of a national rank and file movement.

THE FIRST National Rank and File Movement Delegate Conference took place on 30 March 1974. The initiative that brought the Organising Committee of delegates from various rank and file papers together was taken by members of IS. As with the calling of the first National Minority Movement Conference, the aim was to bring the various existing strands of rank and file militancy together rather than to provide a substitute for that militancy. Since 1969 IS members had played an increasingly active part in a wide range of industries and unions, and in several of these, principally in the white collar area, they had established fragile but meaningful rank and file organisation, usually grouping IS and other militants around a journal or paper. The debate had begun inside IS in 1972 as to whether these groupings were firmly-rooted enough to be welded into a national movement, but action was precipitated by the failure of the only possible alternative, the Communist Party front organisation, the Liaison Committee for the Defence of the Trade Unions. It indicated clearly at its 31 March Conference in 1973 that under no circumstances would it allow any democracy or calls for action that might embarrass the left trade union bureaucracy. IS then began to argue explicitly for the building of ‘a genuine, democratic rank and file organisation of militants’.

One year later, under the changed circumstances of a minority Labour government brought to power by the 1974 miners’ strike, the first NR&FM Conference took place. It was sponsored by the following rank and file papers: Collier, Carworker, GEC Rank ‘n’ File, London Transport Platform, Hospital Worker, Rank and File Teacher, Tech Teacher, NALGO Action, Redder Tape and Case Con. The Communist Party-controlled papers, Flashlight and Building Workers Charter, and the dockers’ rank and file paper Dockworker, were the only papers of any significance which did not sponsor the Conference. Some 500 delegates from 270 trade union bodies reflecting the main areas of recent rank and file activity attended, a considerable achievement in the face of sniping sectarian attacks from many individual Communist Party members and from the organised right wing.

They included some 51 AUEW bodies, two of which were District Committees, 37 TGWU bodies, 28 NALGO branches, 12 NUT bodies, 9 CPSA branches and 19 Trades Councils.

The first Conference amended and added to the draft resolution from the Organising Committee and outlined a general programme for the movement:

Eight months later the Second NR&FM Conference was held, at the peak of an unofficial strike wave taking place largely in Scotland, but also spreading to England. Organised this time through a direct appeal for delegates from the Organising Committee itself, it met a well-orchestrated smear campaign from the Communist Party and the right wing. They could no longer dismiss it as ‘ultra-left sectarianism’ or just ignore it. They had to prove its evil nature by revealing the not very startling truth that many IS trade union militants play leading roles in it. ‘Purple’ passages from my Industrial Report to the last IS Annual Conference were circulated anonymously and published in the Morning Star. Notwithstanding this onslaught the number of delegating bodies increased, as did the number of shop stewards’ committees represented, which went up to 49. Resolutions were carried on the fight against unemployment, wage restraint and the Social Contract, on the Shrewsbury pickets and on Ireland and the bombings. The three Organising Committee officers were re-elected and a series of on-going activities endorsed.

These continuing activities have won the NR&FM its present admittedly limited credibility in the labour movement. The small-scale initiatives like organising the adoption of Chilean trade unionists, opening the Shrewsbury. Dependents’ Fund, supporting victimised trade unionists, and running schools on safety, racialism and the shop floor struggle for equal pay remain the ones where it can be most effective. Some 150 delegating bodies attended both Conferences and the number of bodies which regularly respond to most of the Organising Committee initiatives is probably around the 100 mark. Thus it would be absurd to ignore the fact that the NR&FM still falls far short of what is needed.

THERE ARE two major problems facing the NR&FM. Firstly, how to strengthen the existing affiliated rank and file organisations in their penetration into their respective industries and unions. For unlike the bureaucracy it is attempting to challenge, a genuine rank and file movement cannot survive on paper members. An active base is vital. And secondly, the NR&FM still has to be embraced by the mainstream of rank and file activity that we’ve already shown is beginning to pick up speed. It has to fight to prove itself a vital addition to their armour. The strengthening of its apparatus by the election of a national organiser will certainly help on both counts. So too will the Organising Committee’s call for a joint NR&FM-LCDTU push to force the TUC to name May Day as the date for strike action in support of the Shrewsbury pickets.

The three main obstacles facing the NR&FM as it attempts to deal with these problems and pull together the various strands of rank and file militancy are

The first year of the NR&FM has seen some progress in challenging all three. Fortune itself is forcing the radicalisation of big parts of the motor and engineering industries as the workers begin to grapple with the most serious post-war capitalist crisis. Our strategy of getting the shop stewards’ movement in the different localities used to working together on temporary committees around a specific issue is the key here. The important thing is not the name the local committee adopts, but whether or not it is a genuinely democratic part of the local labour movement and serious about mobilising the rank and file. If it is then we have nothing to lose by waiting for the need for national connections to filter through to the constituent shop stewards’ committees, since we are convinced this is the way the movement is going anyway.

Our successes against the bureaucracy can perhaps be measured inversely by the evidence of its rising paranoia about us. 1974 saw the expulsion from two union national executives (ASTMS and the Dyers & Bleachers) of two elected supporters of rank and file action. And the February 1975 issue of the CPSA journal Red Tape carries a page-long diatribe by General Secretary Bill Kendall aimed at stirring up calls for disciplinary measures to be taken against IS and Redder Tape supporters. As their continued collaboration with the Labour government creates more rank and file resentment we can anticipate an ever-increasing sensitivity to criticism, as Luxemburg suggests in the passage quoted at the start of this survey, and we will come under repeated attack. Rank and file organisation will survive and be expanded to the extent we successfully orientate it both on the factory, office or schoolroom floor and on the union machine.

The organisation of an 800-strong NR&FM meeting in the Central Hall, Westminster, on 14 January, and the earlier march and rally from Euston were certainly the strongest challenge yet thrown at the Communist Party. Jim Hiles and Kevin Halpin, Secretary and Chairman respectively of the LCDTU, found themselves impotently trying to stop other Communist Party members from entering the hall. And the Morning Star’s front page smear attack on the ‘extremists’ alleged to be splitting the movement for having called for a mass demonstration from Euston first was totally ignored by 4000 demonstrators.

The Communist Party is in a highly uncomfortable situation. Its Trojan horse ‘left trends’ within the bureaucracy have moved to the right. Ken Gill, Communist Party General Council member, actually told the disbelieving 1974 TUC, ‘There is no division between left and right in the Congress’, and went ahead to prove it by pulling his punches against the Social Contract. The Communist Party cannot, however, disentangle itself from its own reformist illusions, even if it wanted to. 25 years of the British Road to Socialism‘s analysis that working class advance will come through Communist Party unity with the left reformists means that when the bureaucracy moves to the right the Communist Party ignores the signs and follows. Rather than mobilise the rank and file against these betrayals it prefers to pursue a ‘dialogue’ with them.

The Communist Party’s relationship with the rank and file has therefore shifted dramatically since its earlier revolutionary days in the 1920s. Bloomfield wrote last November:

‘Thus it is to strengthen the left trends at all levels of the trade union movement that -we support bodies like the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions. We see the LCDTU as a vehicle for boosting working class action and the left within the movement ...’

If rank and file action helps increase the strength of the left bureaucracy, then the Communist Party will support and indeed initiate it, as in 1969 and 1970. But if there is a conflict between the demands of the rank and file and the policies of the left, then the Communist Party will do nothing to aid the former.

It will oppose any attempt to democratise its proceedings by allowing resolutions from the delegating bodies at LCDTU national conferences, or by moving to set up genuine, rank and file committees in the localities, and it will side with the bureaucracy in opposing all moves by others to build a rank and file movement.

The embarrassment of the Communist Party hierarchy at the events of 14 January, however, and the clear evidence that the NR&FM was growing in the vacuum left by the retreat of the LCDTU since 1973 has now prompted its convening the first well publicised national LCDTU Conference since Labour was returned to government. While ready to go along with firmer action on the Shrewsbury pickets, the left bureaucracy will make it very clear to the Communist Party that conditions for continuing their ‘dialogue’ will be that the Conference takes no positive steps to seriously challenge their support for voluntary wage restraint. Paper admonitions will be allowed, but there won’t be a lot of room for sharp verbal criticisms and none at all for action. In this situation the NR&FM can only strengthen itself in the eyes of the labour movement as a whole by welcoming the potential offered by the Conference and by putting forward proposals for joint rank and file activity.

ONE AUEW delegate to the first NR&FM Conference explained how he won his credentials to Socialist Worker:

‘I said how in our union you have someone like Scanlon, who hides behind his “left” image, and then, when it comes to the crunch, he backs down. What we need is a strong rank and file movement that will put pressure on the union leadership but is ready to organise independently.’

Now, on top of the crunch of steadily worsening unemployment, the crunch of TUC-imposed wage ‘restraint’ is coming, following soon after no doubt by government wage controls. Whether we believe the ‘left trends’ in the union bureaucracy will defend us, or whether we say it is the strength of shop floor and rank and file organisation that is critical is therefore very important. A long period of piecemeal defeats, coupled with increasing state repression, could set back the possibilities for the emergence of a mass rank and file movement and a mass revolutionary socialist party several years.

The objective conditions are present, the lessons are available from the past, and the International Socialists over the years have provided the theoretical framework. But there is not all the time in the world and it will be far from plain sailing. Much will depend upon the conscious effort put into building rank and file organisations by present IS trade unionists and our supporters. Far from being ashamed that our puny organisation is alone seriously trying to build towards the socialist future with the living bricks of the contemporary labour movement, we must be proud of the fact.

Engels wrote 130 years ago that in strikes ‘is developed the peculiar courage of the English’; ‘as schools of war they are unexcelled’. Let’s make sure that the lessons are learnt and that this courage is not dissipated. Our main priority over the coming year must be to nourish the various fragile roots of rank and file organisation while erecting between and over them the patchwork umbrella of a national movement.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 30.1.2008