ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism, No.83, November 1975, pp.19-22.

Transcribed & marked up by by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

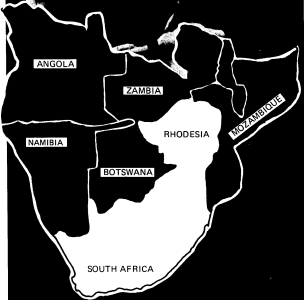

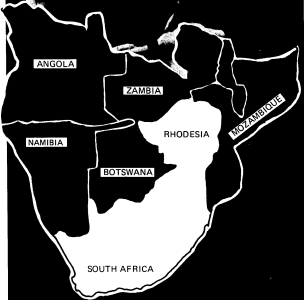

A GREAT deal has happened in Southern Africa over the past six years but it is to 1969 that we must turn in order to begin to understand the developments of the past year. For in that year many of the major interests and parties in the subcontinent were involved in critical moves.

|

The Lusaka Manifesto was signed in 1969 in which the states of black Africa agreed that they would deal and negotiate with the white minority ruled south provided that changes in the structures of minority rule were being seriously discussed. 1969 also saw the beginnings of South Africa’s official ‘outward-looking’ policy, the policy of ‘Dialogue’ with whatever African leader they could find, with a view to extending the penetration of South African capital and influence in Africa. The Cabora Bassa hydro-electric plant in northern Mozambique was begun that year, Partly as a result of this, the Frelimo guerillas opened up a new front in Tete province and this was to prove the decisive breakthrough which led to their victory and the collapse of Portuguese rule last-year.

It was also in that year that the Nixon/Kissinger administration in America produced a report on Southern Africa which marked a turning point in US policy. This secret report, just published in UK (by Spokesman Books, called The Kissinger Study on Southern Africa) outlines five policy options ranging from total support to the white minority regimes to support for liberation movements or total disassociation from the area. Kissinger opted clearly

‘to encourage moderation in the white states, to enlist co-operation of the black states on reducing tensions and the likelihood of increasing cross-border violence and to encourage improved relations among state: in the area’.

From 1969 then, there have been clear moves on the part of South Africa and the imperialist powers to create a new stability for capitalism in the area under the hegemony of the existing white ruling-class in South Africa. This involves co-opting the rest of the area firmly in the neo-colonial gripp. Whe past year has seen the time scale of such operations compressed by the dramatic events in Mozambique and Angola.

Against these forces have been ranged the two thrusts of black resistance. One, the guerilla struggles, reached a high point with Frelimo forcing Portuguese capitulation in Mozambique. The other force is the black working class, primarily in South Africa, which over the same six year period has produced a new wave of the fight against the racist system in South Africa. This began with the black student movement (SASO), advocating ‘black consciousness’, which has been severely attacked by the state but over the past three years has also meant the growing strength of organised black workers in the struggle against capitalism as well as racism.

The only settled issue in the turmoil of events is Mozambique independence. The détente moves initiated by the South African-Zambian alliance (see Notes of the Month, IS Journal, June 1975) are still the keystone. A resolution of the Rhodesian ‘problem’ which causes no disruption to the exploitation and profit-making, and the prevention of a popular movement gaining control of Angola are the main objectives of imperialism at the moment.

Other developments are a reminder of the importance of the area to western capitalism. NATO has recently been exposed as having secret dealings with South Africa and although Britain is formally ending the Simonstown agreement this will make little difference to the military collaboration with South Africa. The ailing British Steel Corporation is proposing massive investment in South Africa’s forced labour system and is being defended by the official ‘left’ in Britain. And the US government has produced another report highlighting the importance of Southern Africa as a source of strategic minerals.

Rhodesia and Namibia are first and second respectively on the detente agenda. The two situations have much in common: an internationally outlawed white minority regime: huge mineral resources and potential; long histories of black resistance to white rule, which now combines exile-organised guerilla actions near the border and urban-based political movements. In both situations, South Africa holds considerable sway and is hoping to bring about solutions which smash the revolutionaries, accommodate the ‘reasonable, moderate’ blacks, get the whites to accept some reduction in their monopolistic hold on political power without reducing their economic privilege, and, above all, secure South Africa and western capitalist interests in the area.

In Rhodesia, for more than a year now South Africa has been openly pressing the Smith regime to a settlement which will lead to an eventual black government, legality and stability. The British government’s role, though less than in the earlier fiascos of attempted deals with Smith, has nevertheless been to try to find ‘an honourable way out’ for Smith. Meanwhile, the liberation movements have been cobbled together through the directives of the African parties to the detente package, under the loose umbrella of the ANC (only to be used when it’s raining, as a ZANU representative commented!).

The likelihood of the neo-colonial settlements depends on two factors; the scope of Smith and his regime to wriggle off successive hooks; and the determination of the liberation movements and the mass of black people in Rhodesia to resist a sell-out and to continue the struggle.

It is unlikely that Smith can resist the pressures on him for much longer. Mozambique is cutting off access to the ports and the South Africans are pulling out their troops from Rhodesia. There are signs that the current round of talks in Pretoria have reached some sort of agreement. South Africa can bring irresistible pressures to bear to avoid a disruptive outcome. The whites in Rhodesia are operating on two fronts: the one which has just increased defence expenditure by 24 per cent and is calling up many more (including recent immigrants) into the army and still holding hundreds of black detainees; the other is preparing to adjust to the inevitable changes. The fascinating account of a visit by two white farmers (officials in the Rhodesian Farmers Union) to Zambia to meet white farmers there and talk with government officials including President Kaunda (reported in Socialist Worker, 28 June 1975) reveals the extent to which whites are prepared for and confident about a handover to black rule as well as the key role of Kaunda in ensuring no vested interests are damaged.

The resilience of the ANC and its component parts is far from certain. There are clearly some elements, most notably Joshua Nkomo, who are willing to do deals to secure their power in an independent Zimbabwe. He has powerful supporters, not least Kaunda, and it is obvious that Smith and Vorster see him as the man they want to settle with. There are others, however, from each of the movements, but probably more represented in ZANU, who see detente as a fraud, see South Africa and imperialism as the enemy and who talk about the need for a socialist revolution. Whilst the armed struggle, ‘Chimurenga’, must inevitably be the front line of that struggle it is only with the involvement of the masses in the towns and of the power of black workers that a socialist Zimbabwe can be built. The danger at the moment is that the ‘armed struggle’ is going to be used by the ANC leadership purely as a tactic of pressure on the Smith regime to hand over to a section of the black bourgeoisie.

In Namibia (which South Africa rules as a fifth province) they are trying a number of ploys. They have to offset, on the one hand, the toothless threat of the United Nations which can set deadlines but is paralysed (primarily by the veto powers of Britain, France and the USA) from taking any action; on the other hand, the sustained opposition from Namibia’s three-quarters of a million blacks. One plan, being implemented sporadically, is to create up to ten puppet Bantustans, leaving the 90,000 whites in control of the main parts of the country and the economy, as the Bantustan policy in South Africa does. Another plan occasionally floated is to partition the country by hiving off Ovamboland in the north, where nearly half of the blacks live and where the main guerilla activity is, leaving the rest to be incorporated into South Africa.

SWAPO (South West African People’s Organisation) maintains a certain threat potential through its guerillas and its diplomatic activity, whilst there are also strong political developments inside the country, now operating under a reformed National Convention. They stand firmly on the platform of a united independent Namibia. One can only assume that the spirit generated by the tremendous strike of migrant workers at the beginning of 1973 is being channelled into such a movement. Inevitably, events in Angola will be a great influence in Namibia. If an independent regime hostile to South Africa comes to power then South Africa’s room to manoeuvre and to stall for time will be severely limited. Hence she is prepared to intervene in one way or another to prevent an MPLA victory.

The histories of Mozambique and South Africa have been closely intertwined, especially since the gold bonanza of the past hundred years. The interdependency is most clearly seen in terms of labour supplies and trade routes. The Financial Mail, South Africa’s business weekly, is currently asking the question: ‘Can Socialism and capitalism live together?’, and their answer is ‘Yes, if tempered with pragmatism.’ South African businessmen, it reports, have found Frelimo officials ‘accommodating and realistic’. This is the crucial issue for the future of Frelimo’s revolution. Having waged a successful guerilla struggle (which helped to undermine the Caetano regime in Portugal) and having united the people behind them, Frelimo is now faced with the uncomfortable problems and dilemmas of office, in what is in reality a backward and dependent state.

It has a 90 per cent illiteracy rate, famine following the floods and refugees from the war to cope with. It has been estimated that 45 per cent of the GNP of Mozambique derives from services to South Africa and Rhodesia; and an estimated income of £100 million a year from the wages of migrant miners and the gold payments South Africa makes for them.

But the dependency is not one way. South Africa needs the labour desperately and the port outlet at Lourenço Marques, at least until its new port is ready. Beira and Lourenço Marques have been Rhodesia’s lifeline. Although Frelimo have been avoiding giving clear indications of all their moves it is fairly certain they will cut the sanctions-busting trade links with Rhodesia but maintain those with South Africa, aiming to run down the trade and the labour supplies. They will aim at creating more jobs to absorb the 100,000 or so migrants. Meanwhile they will exert pressures for better pay and conditions in the South African mines and this could have important spin-offs.

Internally, the new government intends to take most of the economy, including the banks and foreign companies, into state hands, and to introduce sweeping land reforms to create large-scale collective farms. They are replacing the colonial bureaucracy and ‘expertise’ and building up organs of grassroots participation within the Frelimo party structure, ‘Groupos dynamisadores‘ are being set up in factories, schools, communities, etc. to mobilise the masses.

These moves do not, however, alter the severe limitations placed on Mozambique by the prevailing conditions of Southern Africa. Capitalism in its most virulent, South African, form is in control and though the past year in Mozambique has dented it considerably, it can only be finally overthrown in its heartland.

So the extent to which Mozambique can aid the revolutionaries in Rhodesia and South Africa is crucial. They cannot fight the South African revolution but they can make a significant difference. At the very least they can hold firm against the detente moves which are aimed at producing a solution acceptable to South Africa (and if they succeed will be undermining the gains made in Mozambique). In the immediate future that will be the test of Frelimo’s anti-imperialism. In the longer run it will be seen in the extent to which the workers hold power and in how they can use that power in spreading the revolution to the rest of Southern Africa.

Angola is in a very different position to Mozambique. It has tremendous potential riches in oil and other minerals and is a major concern for Imperialism. It is dealt with in a separate article.

South Africa is an advanced capitalist country firmly integrated into the world system. It is the economic giant of Africa, an industrial giant which is the mainstay of capitalism in the area and within it is a massive working class. It is this industrial proletariat, an almost exclusively black, racially oppressed and super-exploited class, which represents the potentially revolutionary force capable of liberating the whole of Southern Africa and shattering imperialism’s hold on the continent. Over the past three years this giant has awoken and posed the South African system its biggest threat. Strikes, overtime bans, demonstrations, a generally militant approach to wages and conditions, and the formation of new independent trade unions now linking up in a federation, have affected the whole country.

This movement began in late 1972 with the dockers and the strike of migrant workers in Namibia, reached a high point in February 1973 in Natal when between 60 and 100,000 black workers came out on strike in the space of less than a month, more or less paralysing the city of Durban. Since then strikes and disputes have been a regular occurrence. During 1974 there were 374 recorded stoppages involving 58,000 workers spread throughout the country. The textile and engineering industry of Natal remained a focus of the struggle but the Witwatersrand was also severely hit and the smaller industrial area around East London was hit by strikes involving 10,000 workers including bus drivers, who thereby stopped the daily flow of migrant labour from the neighbouring Bantustan township to the city.

Workers and bosses and the state are learning from the struggles. Often employers have responded by sacking those on strike; police have intervened to make arrests and forcibly disperse strikers. But in a number of the multinationals wage rates were forced up by the strikes. Now their response is getting more sophisticated, involving new legislation to set up Works Committees (as a way of taking the steam out of the new black trade unions) and even allowing for the theoretical possibility of legal strike action under certain extremely stringent conditions. Bantustan leaders and other blacks who have positions within the apartheid structures have often been used in an attempt to divert and divide the workers.

But black workers themselves are also learning from the struggles. Probably the single most telling statistic is the 50,000 African workers who have joined the 20-odd new black trade unions which have been set up independently of, and often in the teeth of opposition from, the white unions, which vigorously protect the interests of the white labour aristocracy against blacks. Several of the struggles, including one at Leylands assembly plant in Durban in 1974, have been over recognition of the new unions. Given the nature of racial oppression of blacks and their central importance as productive workers in capitalism, the new organisation of black workers constitutes potentially the most revolutionary force in Southern Africa. Their position as blacks under a fascist state inevitably makes each of the struggles highly political.

There are some signs of an awareness of the need for a political party. As Sam Mhlongo, one of the most perceptive of black South African commentators said in his article in Race and Class (January 1975):

‘... because the African worker has no political rights, coupled with the repressive and brutal nature of the state, the very moment he goes on strike he is breaking the law. His only form of struggle against the capitalists assumes a political character and the questions of politics are part of the everyday struggle of the workers.’

Many of the struggles are taking place in subsidiaries of British-based multi-national companies: in Leylands, ICI, GEC, GKN, Metal Box, Courtaulds, Unilever, etc. More than 500 British companies have subsidiaries or associates there. Total investment runs to £2,000 million, 60 per cent of total foreign investment in South Africa. British capital has been crucial at each stage in the development of the economy from the financing of the gold boom to the modern computer industry.

This provides us in this country with two things: a built-in understanding of the links between British and South African capital and the importance to British companies of the super-profits to be made there; and secondly clear possibilities for intervention and solidarity action, not passively out of sympathy for the downtrodden blacks, but concrete support for the on-going struggles of black workers. The days of consumer boycotts, conscience-salving gestures or investment withdrawal campaigns (never of more than propaganda value) are over. We must now be building links between organisations of workers here and in South Africa with a view to blacking goods, campaigning against white emigration and organising strikes in solidarity with black workers in South Africa.

Another important feature of the ferment sweeping South Africa has been the events in the mines, the traditional backbone of the economy. There had been, until recently, relatively little militancy since the famous 1946 strike of black miners, mainly because of the high proportion (up to 80 per cent) of foreign migrants and the conditions in the compounds where migrants are penned in, split up on ethnic grounds and forcibly repressed.

The violent outbreaks in the mines have been a reflection of two things: the inhuman conditions which inevitably produce violent responses either against the authorities, often the black boss-boys or company police, or against fellow workers of different ethnic groups who are kept in separate pens; and secondly, the appalling wages. Many of the incidents, including that at the Western Deep Mine at Carltonville, near Johannesburg, in September 1973 when police killed thirteen black miners, were strikes for better pay and conditions.

There have been two major results from these incidents. Firstly, many miners have been leaving the mines and not returning. Two governments (Malawi permanently and Lesotho temporarily) banned recruiting by the mining companies in protest and under pressure from their citizens. Mozambique supplies 100,000 (25 per cent of the total) migrants to the mines and it is likely that will be reduced. Figures show that the mines are down to 70-80 per cent of their labour supply tnd they are getting worried. An interesting result from this has been that for the first time ever the mining companies have started recruiting in Rhodesia. It is symptomatic of the changing nature of South Africa’s relationship with Rhodesia that she is now beginning to see it performing the same function as the other client states on her periphery, that of a labour reserve. The 2,000 black Rhodesians recruited in May of this year were being offered R.1.50 per shift, much higher than the going rate in the Rhodesian mines. (R.l = 60p).

Secondly, there has been a general and significant raising of the wages of miners and concessionary noises on the issue of trade unions for blacks. Average wages of miners are now nearly R.50 per month, compared to R.34 in 1974 and R.21 in 1972. (They had remained unchanged since early in the century until then). In the same period white miners’ average wage increased from R.454 to R.521! The relative position of black workers has not changed at all, of course.

Black workers’ wages have increased for a number of reasons: the need to compete with other sectors for labour: adverse publicity: and the militancy of black miners.

The big mining companies are expressing worries about the disturbance of their previously peaceful labour relations and calling for the setting up of better channels of communication with their workers. Anglo-American are now advocating trade unions for black miners as a way of trying to stem the tide of unrest. The government has not agreed to this yet. A revealing comment by the . head of the white trade union federation, TUCSA (which has close links with our TUC) indicates ruling class thinking on the matter. He said:

‘The Minister of Labour must come out of his ideological ivory tower. He needs to recognise that there is increasing concern among industrialists and entrepreneurs in South Africa that the present system of industrial relations is not satisfactory and does not spell good business for them. He must stop being a threat to both our internal and external security.’ (Rand Daily Mail, 15 August 1974).

Wage increases and moves towards trade unions for blacks throughout the economy are manifestations of a general trend away from the rigidity which has characterised much of South African policy until recently. There have been other moves to attempt to satisfy certain limited aspirations of blacks within the limits of government policy and aimed tentatively at the consolidation of a black middle-class. There will certainly be more in this direction.

Africans are now to be able to lease houses for up to 30 years in the townships of ‘white’ South Africa and trading licences in those same areas will be easier to get. Some of the restrictions on Asians and Coloured people are being eased in an attempt to woo them to support the whites and the status quo. And the Bantustan leaders are constantly being promised their mythical ‘independence’ and being given a few more acres of land.

Is this, as some liberal commentators try to make out, a sign of the cracking of apartheid, the proof of the decency of the whites or of the validity of exerting pressure through capital investment and other contacts? It is, only if one sees the South African system in very narrow and naive terms – that is, of nasty white people holding down poor black people. What is happening is that South Africa is beginning to behave more like a ‘normal’ capitalist state. Those who have for long been arguing the logic of such action (the ‘English’ Establishment, representatives of international capitalism and more recently the burgeoning Afrikaaner industrial bourgeoisie) are now being heeded much more. One such advocate, The Star newspaper said in a recent editorial:

‘South Africa must become an enlightened capitalist state which offers equal opportunities and an effective say in government for all its people. It must convince its black and brown citizens that it offers them as much dignity, opportunity and prosperity as Mozambique offers its people.’

That, of course, can only be achieved by keeping Mozambique in a state of client poverty. Even then the convincing of the ‘Black and Brown citizens’ is going to be difficult since it is based on the fraudulent ‘Separate Development’ idea. Nevertheless this gives some indication of what South Africa claims it’s doing and also of the contradictions it is up against. More than ever, it means that South Africa must be analysed in terms of class rather than simply race. Far from being a unique racist ‘aberration’, South Africa represents capitalism in its most highly exploitative and repressive form.

South Africa is moving to contain the forces pitted against it both externally and internally. To analyse how it is trying to do this is not to assume it will or ever can succeed in the long run. As the liberation movements and those revolutionaries in Africa who see South Africa as the barrier against liberation and socialism fight on, so the black working class in the heart of South Africa’s power fights its battle. The latter has the power to break that system and combined effectively with the former will be an unstoppable force.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 22.2.2008