ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism (1st series), No.93, March 1976, pp.3-6.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

THE CRUNCH IS NOW proclaimed the Daily Mirror (7.10.76) on a front page given over entirely to the speeches of Callaghan (’Britain is now at a watershed. We have lived too long on borrowed time and borrowed money’) and Heath (’We have come to the end of the present road’).

Allow for the usual exaggeration, the normal rhetoric of conference speeches. The fact remains that the Labour government’s strategy, plans, hopes and targets lie in ruins.

Inflation was to be brought down to single figures by September 1976, later extended to December 1976. It is now running at around 14 per cent, annually, after rising from 13 per cent in mid-summer, and is set to rise further. Manufactured food prices rose by 314 per cent in September and a new inflationary surge is in the pipeline, inevitable consequence of the sinking pound.

Unemployment, which was to be avoided altogether under the Social Contract Mark 1, hovers around 1½ million and is certain to rise further under the impact of the present deflationary measures, a 15 per cent minimum lending rate and more cuts (in jobs as well as services) to come.

As to the rising investment which was to follow the ‘export-led boom’ of Healey’s plans, it recedes over the horizon, some well-published plans (e.g., ICI’s new £40 million methanol-protein plant) notwithstanding.

’Fixed investment fell to a new low in April-June (down 3 per cent on January-March) despite a sharp rise in gross trading profits to 7.3 per cent of GNP.’ (Economist, 25.9.76)

And that was before the present record credit squeeze which, if maintained for any length of time, must choke back investment further.

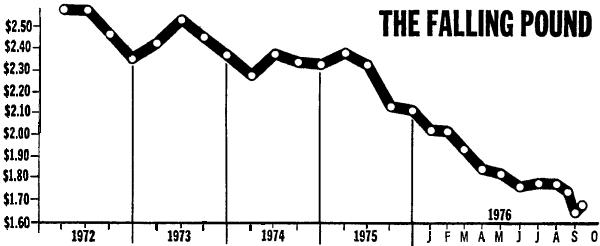

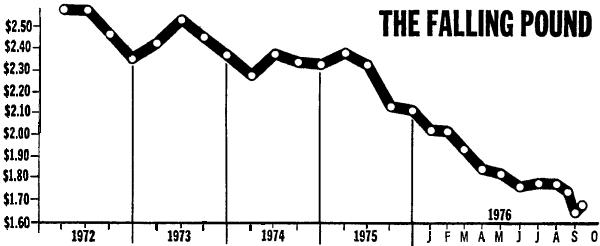

The floating pound was a device guaranteed to prevent sudden currency crises of the old type leading to ‘stop-go’ economic policies – so the experts testified. In fact, sterling slipped from around $2.00 in February to a record low of $1.63 in early October before the most recent (temporary?) pick-up to around $1.66, feeding in imported inflation and making nonsense of repeated government forecasts.

Moreover, the spectacular nosedive from $1.77 to $1.63 in the three weeks from 9 September was exactly the kind of panic surge which floating (exchange rates were supposed to make impossible. And it took place in spite of the still far from exhausted $5,000 million stand-by credit obtained in the summer.

|

Leave aside the question of causes – the run-down of the oil states’ sterling balances by at least £1,500 million causing the long-term slide and the deliberate decision by Callaghan and Healey to precipitate the September drop to blackmail the seamen’s union leaders – the facts that stand out are the extreme instability of the exchange rate and the inability of the Treasury to see beyond the end of its collective nose.

The government is now in the arms of the IMF and, whether as a result of direct IMF pressure or not, has committed itself to a deflationary course which must make nonsense of its industrial strategy and, in the longer term, aggravate all the problems of the economy.

But ‘the end of the present road’? Certainly not in terms of economic policy. After pontificating on the evils of living on borrowed money Callaghan has recourse to – a new large loan and the deflationary strings that go with it!

Basic policy is unchanged. The gamble that the increased profits obtained by pushing down real wages (and cutting social services) will actually be used to produce the long-promised ‘surge of investment’ remains at the heart of the government’s hopes. Yet by raising interest rates again it has made it decidedly more profitable to invest in government stock than in new plant. And the Treasury aims to sell £3,500 million worth of such stock by the end of the financial year in order to reduce the rate of growth of the money supply. The more successful this operation, the lower the rate of investment.

The inevitable failure of these measures – in terms of the government’s own objectives – will produce a new round of calls for ‘sacrifice’, ‘belt-tightening’ and so forth. It is in the political consequences that the talk of ‘a watershed’ has some real meaning.

THE government has had the most favourable political conditions conceivable over the last two years. The Economist (2.10.76), in calling for yet more savage deflation, praises ‘Mr Jim Callaghan, who is the best c-nnservative prime minister Britain could get.’

It is a question neither of commitment to capitalism – that can be taken for granted with Labour’s right wing – nor even of personal qualities. Callaghan is ‘the best conservative prime minister’ available because, in spite of having torn up the key promises of the Social Contract on the government side, he, and the government generally, has been able to pull the TUC into even closer cooperation with the policy of wage-cutting.

’The recalcitrant National Union of Seamen was dealt with by the General Council of the TUC playing to all intents and purposes the role of the employer’ noted Peter Patterson (Evening Standard, 12.10.76). ‘Once the TUC had finalised the bargain with the union, the Shipping Federation was brought in to rubber-stamp the deal.’

When the Social Contract was first announced (September 1974) the TUC’s official sheet, Labour, declared

’... the present priority in pay negotiations should be to win something extra for the low paid, and hold and protect the purchasing power of the rest of us.’

This was duly embodied in the formal eight point agreement; ‘a central negotiating objective in the coming period will-therefore be to ensure that real incomes are maintained’ (Point 1).

Since then real (working class) incomes have fallen by three to five per cent. And the TUC bullies and blackmails the NUS into abandoning its modest claim – in the name of the Social Contract!

Then, in 1975, the government, with full TUC backing introduced the £6 limit. The emphasis of the argument shifted to pay control as the alternative to mass unemployment.

’To try to cure inflation by deliberately creating mass unemployment would cause widespread misery, industrial strife and a total degeneration of our productive capacity. The only sensible course is to exercise pay restraint and reduce our domestic inflation without sacrificing our long-term economic goals.’ (White Paper Cmnd. 6151)

The £6 limit was observed. Unemployment soared to a level unknown since the 1930s. Inflation continued. The ‘long-term economic goals’ have been sacrificed. Still the TUC exerted all its efforts to prevent working class resistance.

This year, when the 4½ per cent pay rise limit was introduced, the General Council persuaded Special Congress to endorse it by an 18:1 majority. And at the time of writing (13.10.76) the TUC is assuring the government that its support of pay policy will not be affected by the credit squeeze.

No openly Tory government, least of all one with the Thatcher-Joseph emphasis, could have hoped to secure such victories for British capitalism – or can hope to in the future.

The collaboration is beginning to fray at the edges. In particular, some of the public sector union leaders are moving towards countenancing token actions against the cuts – which will cut their membership. And the seamen’s ballot in favour of industrial action (by a hairsbreadth) is an ominous omen for the TUC bosses.

In the main, however, there is still near unanimity on the general line of support for the government. This, in turn, would have been impossible without the collapse of the ‘lefts’. It is hardly necessary, at this point in time, to discuss the role of yesterday’s heros of the ‘broad left’: Scanlon, Jones, Daly, McGarvey and the rest.

What is relevant here is the extent to which the actual motor of the ‘broad left’, the Communist Party itself, has accommodated to the rightward drift of its former and present allies.

A small but significant incident will serve to illustrate the point. Confronting a crowd of Right to Work demonstrators outside the Brighton TUC, a CP Congress delegate poured cold water on the significance of the demonstration and boasted that ‘we have more than a hundred party delegates in Congress’. Probably true. But what did they do there? They made no attempt even to mount a demonstrative intervention inside Congress – that was left to an IS delegate – nor any attempt to mount their own demonstration outside. Even seven years ago this would have been inconceivable. Then, through the LCDTU, mass demonstrations were mounted against the Wilson-Castle anti-union bill and later against the Heath-Carr bill. Now, with 1.5 million unemployed they mutter about ‘ultra-left adventurism’!

The cosy relationship it has built up with sections of the trade union bureaucracy has made the CP unwilling – and probably increasingly unable – to mobilise against policies which the Morning Star daily proclaims to be disastrous. As John Deason shows in his article in the present issue, the CP is now concerned to weaken the initiatives taken by the Right to Work campaign – and not mainly by the obvious method of employing their, on paper, much superior forces to mount their own operations but by blocking with the right to [do so.]

In 1969-74 the CP played a "dual role. It always sought to limit action, to channel it in party approved directions with one eye always on the ‘left’ leaders. But it was also prepared, within limits, to organise actions. Now its role, as an organisation, is almost wholly negative.

Nor have the ‘left MPs’, upon whom some people placed large hopes, been able to bring themselves to mount any consistent and determined attack on Callaghan’s Tory policies. True, the Labour Party Conference did pass some critical resolutions, including condemnation of the cuts, but it also endorsed the Callaghan-Healey policy!

Whatever may be the case in the longer term, it is clear that there can be no realistic expectation of any fight from this quarter in the immediate future.

The Tribunite lefts and the CP, and for that matter the TUC General Council and the Bennite section of the Cabinet, do indeed have an alternative policy. It centres around import controls, phasing out of sterling as a reserve currency, state directed investment in industry and so on.

It is not inconceivable that some or even all of these measures may be taken in conditions of severe crisis – although, on past experience, more likely by a strong Tory government than a weak Labour one – for there is, of course, nothing inherently ‘socialist’ in them. They involve sacrificing certain capitalist interests in the interests of British capitalism as a whole.

But more to the immediate point, they are by their very nature measures that cannot be achieved by direct working class action. They are not issues around which effective action can be mobilised. On the contrary, they are a diversion, an excuse for not mobilising action – quite apart from their reactionary, nationalistic content.

THE ‘established’ left has failed to provide a channel for discontent to express itself through; still less has it sought to mobilise discontent to resist the government.

But the discontent is there and it is growing. It is finding other, more reactionary channels – racism, fascism and a swing to the increasingly racist appeal of the Tory Party. The slump of the Labour vote in both Rotherham and Thurrock and the increase in both the Tory and the fascist vote is significant and ominous. It may well be the case, as Martin Shaw argues in a discussion article in this issue, that the chronic economic crisis is producing a sea-change in the long static British political superstructure.

In any case it is certain that the growth of fascist support is a direct consequence of both the government’s reactionary policies and the essentially nationalist and bureaucratic response of the ‘established’ left. Their line is not only an expression of impotence with respect to Callaghan. It is a guaranteed method of strengthening the right, including the growing fascist right, notwithstanding the quite contrary intentions of its sponsors.

In these circumstances it is essential that the revolutionary socialist alternative is presented wherever the fascists (and the Tories) present their alternative, and that must mean in general political terms.

Of course it is true that there can be no serious and significant revolutionary socialist force that is not rooted in the workplaces and, at one remove, in the unions.

Taking this for granted, the question is what is the next step, how, concretely, do we move towards this goal in the specific circumstances of today?

We have always been critical, rightly critical, of self-proclaimed ‘leaderships’, of chest-beating and rhetoric, of confusing wishes with real possibilities. Taking this too for granted, it is clear that a ‘more of the same’ orientation would be an abdication of responsibility in this situation of growing crisis. It is necessary for revolutionaries to make a turn, to respond to the opportunities – and dangers – of a new situation.

These questions have been under debate in the International Socialist organisation and have led to specific conclusions. The next section of these Notes reproduces the substance of some of these conclusions, agreed at the September IS Council. We print this previously internal statement for information and discussion among all those seriously concerned with the need to create the revolutionary socialist alternative to Callaghan, Thatcher and Webster as a matter for immediate action.

’THE whole situation forces us to act as a party while our forces are still slender.’ (Political Perspectives for Conference 1976, in March IS Bulletin)

The political situation, as outlined in Conference documents, can be summarised briefly as follows. The Labour government moved rapidly to the right after the victory of the right wing in the Common Market referendum, as we predicted it would. From a government concealing the realities of pro-capitalist policies with a screen of reformist rhetoric it has become openly conservative. It is a government whose only solution to the economic crisis is to increase profits, to cut real pay, to cut the social services and to maintain a massive level of unemployment as a means of enforcing these policies.

In the face of this gallop to the right the TUC has collaborated all along the line; even verbal opposition has been largely confined to a few public sector union chiefs who stand to suffer significant membership losses as a result of the cuts.

As the TUC has moved rightwards the CP dominated ‘broad lefts’ have been dragged along at one remove, protesting but unwilling or unable to put up any real fight. The CP’s lack of fight and, in many cases, its obstruction of those trying to fight have prevented it from becoming a pole of attraction to disgruntled workers.

The ‘left MPs’ are waiting for the TUC. or at any rate some important union leaders, to oppose the government and no significant left wing movement has developed in the Labour Party membership organisation.

Meanwhile discontent is finding other and reactionary channels – racism, fascism – as yet on a fairly small scale but the ominous symptoms are clear enough.

A month after Conference the Central Committee issued a directive (dated 24 June) which stated:

’... the twin themes of fighting racialism and fighting for the right to work now dominate our immediate perspective for the next few months.’

The vigour and enthusiasm with which members have thrown themselves into this work, together with events themselves (the racist murders, community reaction, the fascist election successes, the continued rise in unemployment) have changed to some extent the political situation of our organisation.

This shows itself, firstly, in a real pick-up in membership after a long period of stagnation. Secondly, in a marked increase in the morale and self-confidence of members. Thirdly, in a significant improvement in the standing of our organisation amongst uncommitted left-wingers and militants.

It is important not to exaggerate these gains. We must always maintain a sober and realistic appreciation of our true strength and weaknesses. But it is even more important to grasp our opportunities; to understand the need for bold initiatives in appropriate circumstances.

The whole experience of 1976 demonstrates this. The Right to Work Campaign was started at the beginning of this year after prolonged and sometimes bitter dispute within our own ranks as to whether it was either possible or desirable.

There cannot now be the slightest doubt that this initiative was right and has had a marked effect in improving our industrial and trade union work as well as starting serious work amongst the unemployed for the first time. In a modest way it has also had an impact on broader sections of the working class movement. More systematic interventions in union elections has played a valuable role in the process.

All this, it is important to note, has taken place against a background of a very low level of industrial struggle and the collapse of the trade union lefts into the arms of the right wing. We seized on those initiatives that were open to us, in a generally not too favourable situation, and this has taught us several things.

We have been and still are the only people attempting an organised fight against unemployment, however modest our slender resources have made our efforts.

The contrast with the lack of activity by the, on paper, greatly superior forces of the Communist Party could not have been more marked. As to the grouplets and splinters of the ‘revolutionary left’, they have (as organisations) been irrelevant; either obstructionist or parasitic on our efforts.

In the fight against racism and fascism, it is the same story. Our organisation (together with a good number of individuals outside our ranks) put itself in the forefront of the struggle, so far as ‘native’ political forces are concerned. The intervention of our comrades against fascist parliamentary candidates, the anti-Relf campaign, the mass postering and leafletting and the demonstrations have been very largely IS initiatives (apart, of course, from the important activities of immigrant organisations).

More than anything else, this anti-racist work has brought us members (including black members) and increased our standing and support. We have to carry this fight forward and intensify it, carry it into new fields. If we do not do it, it will not, effectively, be done. Again, the contrast between our efforts and those of the Communist Party (and of the Labour Party!) is sharp and clear.

These activities, in their turn, have presented us with new problems and shown us new opportunities. One of the spin-offs of the Right to Work Campaign has been the grouping around us of some small but significant groups of young workers. The need for a youth organisation, with all the possibilities and difficulties it involves, is now clearly on the agenda.

The anti-racist work, and especially the need to combat the electoral activity of the fascists, has made the question of our own electoral intervention an immediate issue.

Of course the matter has been discussed before. Of course we have always been in favour in principle of utilising elections for revolutionary purposes; and that means an anti-Labour Party intervention as well as an anti-fascist intervention. Electoral intervention is to put across our politics as a whole, to denounce Labour’s sell outs, to recruit and to gain supporters.

The Central Committee directive on Walsall (20 July) spoke of intervening in every suitable parliamentary bye-election. Any odd splinter group can contest the odd election. If we go into electoral activity at all, and we have decided to do so in the case of Walsall and Stechford (and now Newcastle), we must do it seriously. We must present ourselves as serious people fighting for a serious alternative, a socialist alternative, an anti-racist, internationalist alternative. And that means, not a one-off or a two-off contest, but a systematic intervention in predominantly working class constituencies, whenever the opportunity offers itself.

This has vast implications. You cannot systematically contest bye-elections and disappear in a general election without appearing less than serious. And you cannot seriously contest a general election unless you put up at least the minimum number of candidates required to get television time. That means, under present rulings, 50 to 60 candidates.

But once you speak in these terms you are speaking of a party, albeit a small party, no longer of a ‘group’ or ‘organisation’. You are speaking of a decisive break with small group politics (in which, for quite a long time, we have been by far the biggest group). You are speaking of outdoing the Communist Party on its own chosen ground as the ‘recognised’ far left party. You are speaking of beating the ‘parliamentary readers’ at their own game, without, of course, making the slightest concession to parliamentary roadism. You are speaking of the Socialist Workers Party.

Is this a realistic perspective for the immediate future, for the next year or so? Timing is of the essence in politics. Is this the time? It is very obvious that the difficulties are enormous. It is very obvious that the resources needed; men and women, money, expertise, flair and drive, are greater than we now have.

It is a question of winning these resources by bold initiatives, by uniting around a militant socialist force all those that we can reach in the working class movement, and the youth who otherwise might be attracted to the fascists, who are ready to fight in general political terms, not just industrial ones. It is a question of establishing the revolutionary party which, as the resolution on perspectives passed at conference said, stands for an overall alternative to the CP ‘broad lefts’ and the Labour government as well as to the Tories and fascists. And that means an aggressive, confident drive for more members, more Socialist Worker supporters, more people involved in all our activities, including electoral activities. It means, too, unleashing the tremendous reservoir of talent, capacity and ideas that exists amongst our present members and supporters. To do this, we must make the decision to found the Socialist Workers Party at a suitable date in the near future. We must not, of course, imagine that changing our name will in and of itself achieve anything at all. It is part of a drive to build, to recruit, to turn outwards politically in a more systematic way.

In all this, we are basing ourselves on the general correctness of the political perspectives and political judgements adopted at Conference. They will not be argued again here, since they are readily available to members, but, of course, they are the essential background to the discussion. The question now is how, in a situation that has changed to a certain degree in favour of revolutionary intervention, we display that flexibility’ in seizing the chances of which they spoke; of how we can ‘seize the time’, and prove in practice that we are the revolutionary socialist movement in Britain and that, in truth, there is no other real alternative on the left.

’WITHOUT in any way altering our basic orientation on building rank and file movements, on rooting the organisation in the workplaces and developing the real left opposition in the unions, we must now ‘present overall ideological alternatives – against racism, over the need for socialist planning etc’ (Resolution on Political Perspectives, Conference 1976)

This involves, among other things, electoral interventions to present our politics ‘across the board’.

Such intervention must be systematic and must lead to a large scale intervention in the next general election.

Such interventions must be based on a perspective of winning active supporters for the rank and file movements in the workplaces, for the fight against racism and fascism, for the Right to Work Campaign, for the fight against the cuts and of winning members and regular Socialist Worker readers and supporters. We do not estimate our relative success or failure primarily by votes cast for SW candidates but rather by the members, supporters and contacts won. We aim to recruit members in Walsall etc, to establish an expanded regular SW readership and to widen our industrial contacts. If this is achieved, or even partly achieved, the campaigns will have been a success irrespective of the votes cast for our candidates.

This activity is, essentially, one of the activities of a revolutionary party. We must draw the necessary conclusion and prepare over, say, the next six months or so to establish the Socialist Workers Party. This will involve a determined membership drive, rallies and other actions and a founding event of some kind. Its precise timing and nature will depend on the course of events and must be flexibly determined.

It does, however, mean, immediately, a challenge to the Communist Party with the perspective of destroying its pretensions to ‘lead the left’ and a distancing of ourselves from the sectlets. It means an outgoing and uninhibited political stance, unsectarian but aggressive, based on the confidence that we are now building the revolutionary party in Britain.

At the same time members, supporters and all those who meet our comrades or read our press must be given a realistic assessment of the difficulties and struggles ahead. We are not, and will not be in the immediately forseeable future, an effective alternative to the Labour Party. We speak of the socialist alternative in propaganda terms, in terms of specific and limited interventions and in terms of laying the basis for the mass alternative to Labour. In the short term we have to replace the Communist Party and mount a serious challenge to the trade union bureaucracy (which involves a long hard struggle to displace the ‘broad lefts’ as the opposition). The members and supporters we recruit must become actively involved in rank and file movements.

The time is now ripe for this turn. To some extent we have to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps, but we do it in a situation in which numbers of workers are turning away from Labour and in which we are the only serious left alternative. Without exaggerating our own strength and influence, we have to understand this and act accordingly.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 3.2.2008