John Hampton (Red Wedge Graphics)

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism (1st series), No.97, April 1977, pp.16-18.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

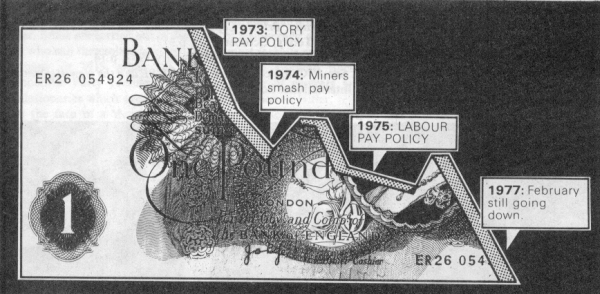

THE fact that real pay has been cut by the Social Contract is now common knowledge. Neither managements nor union leaders would disagree. How much it has fallen depends on which groups of workers you consider, but even the highly misleading ‘average’ figures produced by the Department of Employment show that over the last two years earnings have risen 20.2%, prices 25.7%, so that real earnings have dropped 5.5%. (See Misleading Figures).

|

|

John Hampton (Red Wedge Graphics) |

The fall in take home pay is far greater, as tax eats further and further into pay packets.

The Treasury reckons that real net disposable income i.e. what is left after paying tax and rent or mortgage payments – has declined by 12 to 21% since 1975. As a rule of thumb, it isfair to say that real pay for the average manual worker has fallen by about £10 a week since the beginning of the Social Contract.

The most disastrous effects have been felt by those with the lowest wages – farm workers, hospital workers and shopworkers. Inflation is more severe for families on low incomes because they spend a higher than average portion of their income on food, fuel and fares – all items whose prices are going up faster than the average. According to the National Consumer Council, the difference in inflation rates has become increasingly marked since 1970, and the Retail Price Index is now completely inadequate as a measure of inflation for families with children on low wages. But even white collar workers like teachers and civil servants whose annual increments have continued outside the £6 and 5% limits, have seen their net pay aftertax decline.

|

|

Financial Times, 17 March 1977 |

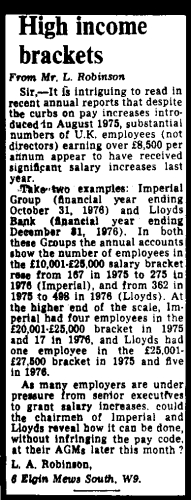

The very highly paid have of course devised ingenious ways of excluding themselves from the pay policy – by creating loopholes, by a massive extension of fringe benefits and perks and by imaginative tax avoidance. In 1976 Sir Humphrey Browne of the British Transport Docks Board, a part-time employee, had his nominal hours of work increased by a third – which boosted his pay from £10,748 to £14,135. Managers of the Trustee Savings Bank had their pay increased by 20% while the rest of us were stuck with 5%, thanks to ‘restructuring’. National Westminster Bank managers, on the other hand, suddenly needed an ‘inconvenience allowance’ of £1.66 a day if they couldn’t get out for lunch. And BOC (the British Oxygen Company) has a complex scheme for its senior managers including low interest loans for house mortgages, furniture and fittings, worth up to £50 a week, with fees from overseas directorships adding up to another £2,500 a year.

Besides dividends, share issues, extra directorships and increases in unearned income there are perks – expense accounts, free cars, school fees, pensions, medical insurance, low interest home loans. HAY-MSL, a group of international management consultants giving evidence to the Royal Commission on Income and Wealth reckoned that for those on £10,000 a year perks were worth 25 to 30% as much again. In 1973/4, the total value of perks declared for tax was £1,908 million between 378,000 individuals – an average of £5,048 each. Another 34,000 people were getting perks worth more than £10,000 a year each! That excludes many non-declared benefits, and two large groups – the self-employed, and the directors of ‘closed’ companies – who control the company expense accounts.

Besides this privileged elite, there has also been a fair bit of successful evasion of the pay limits. A few examples: the computer ‘broke down’ last year in a Midlands engineering firm, when it was ‘repaired’ skilled workers – toolmakers, patternmakers – had an extra £5 in the wage packet; in several Warrington factories, during the £6 policy, skilled groups put in extra claims after the rest of the shop floor had settled and won £10 rises; in a Bradford textile mill a new machine was started and the rate for the whole line was increased.

‘Regrading’ jobs in white collar areas has won many a £10 pay rise.

Other groups of workers have won pay rises outside the limits through legal loopholes, such as the Equal Pay Act. The 1946 Fair Wages Resolution, which allows pay in firms with government contracts to be brought up to the ‘general level’ in a district has been widely used, giving some groups pay rises of 50 to 100%; the Equal Pay Act has been used to give increases to men as well as women. Although this ‘seepage’ is important in undermining the pay policy, it is not where the crunch is coming. Where are the major areas of future conflict?

What has happened to tax?

Tax and National Insurance as a Percentage of EarningsThis graph shows that for workers on average earnings, income tax and Nl deductions have increased to six times their 1950 level – from 4% of earnings to 26% in 1976. But people on three times average earnings (over £11,000 a year in 1976) have only seen their taxes double in the same time – from 17.3% to 33%. Much of the increase has been due to ‘fiscal drag’ – tax allowances are not adjusted upwards as prices and pay (in money terms) rise, so people who previously would pay no tax, or very little, now have to pay large amounts. In 1972, when average male earnings were £35.30, a man with a wife and two children could earn up to £20.12 before having to pay income tax. By 1976, average earnings had risen to £69.20 – but income tax for the same man would start when his earnings were only £27.68. During this time the value of the pound had halved, so not only were gross incomes lower in real terms, but there was a huge reduction in real net pay. (Interestingly, though average male take home pay was £51.90, average consumer expenditure per household was £73.50 – revealing the importance of women’s income). Just to restore personal tax allowances to their 1973 levels (let alone their 1960 levels) would require the following increase: single and wife’s earned income ....... £1,114 The total cost of restoring the value of these tax thresholds would be £3,200 million – or, to look at it another way, since 1973 the Treasury has gained an extra £3,200 million from our pay packets, just by not adjusting income tax allowances. |

Neither the £6 nor the 5% is counted as part of basic pay for the vast majority of manual workers, so that, for example, overtime rates do not include it. For some groups, such as railwayman or Post Office workers, the consolidation of these ‘supplements’ into the basic rate is going to be the number one item on the agenda: it could add £4 to £5 to the wage packet immediately. This could be a very hot issue – some unions are going to be split down the middle when they come to consider the relative value of overtime and shiftwork for different sections of the membership.

The Leyland toolmakers, even though not fighting for an actual pay increase, have brought the question of differentials right to the centre of the stage. The degree of support from other sections of workers, both skilled and unskilled, in and outside Leyland, seems to show besides a general opposition to the Social Contract as such, an awareness of the possibilities of parity and ‘leapfrogging’ claims in the near future. Groups of workers claiming parity with other groups, or claims settled at different times of year ‘leapfrogging’ over each other, are important ways of raising the general level of wages. In the engineering industry particularly, where the national agreement is ever less relevant (the skilled rate is now worth £16.73 at 1973 prices), the importance of local bargaining over such issues as overtime premiums should not be underestimated.

A third major detonator for a pay explosion will be that traditional management frightener: anomalies. In the massive pay explosion that followed Tory pay policy in 1974, the first to move were those who had suffered because of the timing of the policy or because one section of the group had got out of line with another. Workers whose agreements are negotiated in July and August, who were trapped by the pay policy before getting their annual rise, such as Swan Hunter shipyard workers, the seamen, Leyland busworkers are queueing up to have their grievances dealt with. Both consolidation of the pay-policy rises and differentials are important here. If production workers start getting more money for overtime because of consolidation – supervisory staff are going to want their differentials restored.

Where do all these factors – dominated by the massive overall pay cut of the last eighteen months – leave the TUC and government strategists?

The government – whether Labour or Tory – faces a massive build-up of pressure on wages. From the right comes the argument that it is far less costly economically and politically to chop hospitals, school meals, state investment etc. and allow unemployment to soar, than to go through the continual cycle of wage restraint and wage explosion every two years or so.

One strategy which appears to have the blessing of the TUC and the CBI is the need for tax concessions – the demands vary between £1.5 billion and £2.6 billion. Certainly from the CBI and the British Institute of Management much of the emphasis is on reducing taxation for those on higher incomes, paying higher rates of tax. While it is true that people earning over £8,500 a year pay 50% tax on additional income, it is not until incomes of over £22,500 a year are reached that average tax is 50%. At the other end of the scale, tax on additional income (the marginal rate) ranges from 50% to 110% for all incomes between £22 and £55 a week. As we have shown, the increased burden of taxation has fallen most heavily on lower income groups – as have the real effects of the pay policy. Tax cuts should not be seen as concessions – even if Healey announces cuts of £3.2 billion, he is only giving back the extra revenue he took through fiscal drag in 1975/6.

A likely alternative seems to be some tax ‘cuts’ on the one hand, and on the other a low ‘voluntary norm’ with a high margin for productivity increases, incentive payments and so on. At the same time the public sector workforce would be hammered through cash control and natural wastage, with no productivity aIIowances on pay.

The stumbling block is, of course, workers’ organisation, in particular shop stewards organisation in manufacturing industry. Despite the depression of activity of the last eighteen months stewards’ organisation has shown itself incredibly resilient. During the recent mini strike-wave the old links have shown up again and some new ones have been forged. Just a few examples are the links between David Brown factories in the North, the Edgar Allen strikes in Sheffield, the common front adopted by Schweppes maintenance men in the South East, and the number of meetings of stewards and convenors around the Leyland toolroom dispute. While great efforts will be made by the trade union bureaucracy to avoid national confrontation – for example by continuing the undermining of the national engineering agreement – and to limit the extension of the steward’s role outside the workplace, real combine organisation and liaison between stewards committees will be decisive in the coming battles over pay, whatever the particular form they take.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 1.3.2008