ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism, 2 : 14, Autumn 1981, pp. 44–74.

Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg, with thanks to the Lipman-Miliband Trust.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

Just over two years of Tory government have passed in a blur of events. As this article was being written British Airways declared it would make 9,000 workers redundant, and freeze pay for a year after already delaying previous increases by three months; Hoover announced a threat to cut pay by 10% in January 1982; the rail union leaders – from a position of strength – abandoned their strike plans and agreed to a potentially savage assault on jobs through productivity deals; and the 750 workers at Lawrence Scotts in Manchester were still trying to win one of the few fights for jobs in engineering, in the face of total treachery from the officials of their unions, left and right. On 15 September 1981 the new right-wing Tory cabinet took its toughest line on pay, announcing virtually a 4% limit in the public services.

These events are almost symbolic of how the struggle has gone since the Tories came to power. A reactionary government, aggressive employers, enfeebled shop-floor organisation and the most rapid onset of a slump since the early 1930s combined to produce a period of many defeats, many shoddy compromises and few victories. The questions this article tries to answer are: how far these defeats have gone; why have they occurred; how has working class organisation suffered; how confident are the employers; are there signs of a change and, if so, in which directions.

None of these questions have simple answers. The last two years have been unprecedented. This is not just the ‘worst recession since the 1930s’ as we are so often told; it has a unique combination of rapid growth of mass unemployment, continued high rates of inflation matched for a long period by increases in take-home pay, a huge erosion of the heartlands of British capitalism and a persistence of workers’ struggle on quite a large scale. If these are uncharted waters for the trade union movement and for revolutionaries, they are also so for the ruling class, which even after two to three years of consistent gain in terms of shop-floor control is deeply uncertain about what it has won. The period has also seen the emergence of new broad left currents in many unions, a turn to Labour politics by many activists – in sum ‘a political upturn in an economic downturn.’

This series of developments has been so rapid that, more than usually in an article of this sort, it is essential to go over the main events in the class struggle to see what trends and general lessons emerge. The first part of this article therefore summarises general developments. Secondly, there is a look at various sectors and unions. I then review some changes in the employers’ offensive. Finally, coming back to the general picture, I make some tentative pointers to the future.

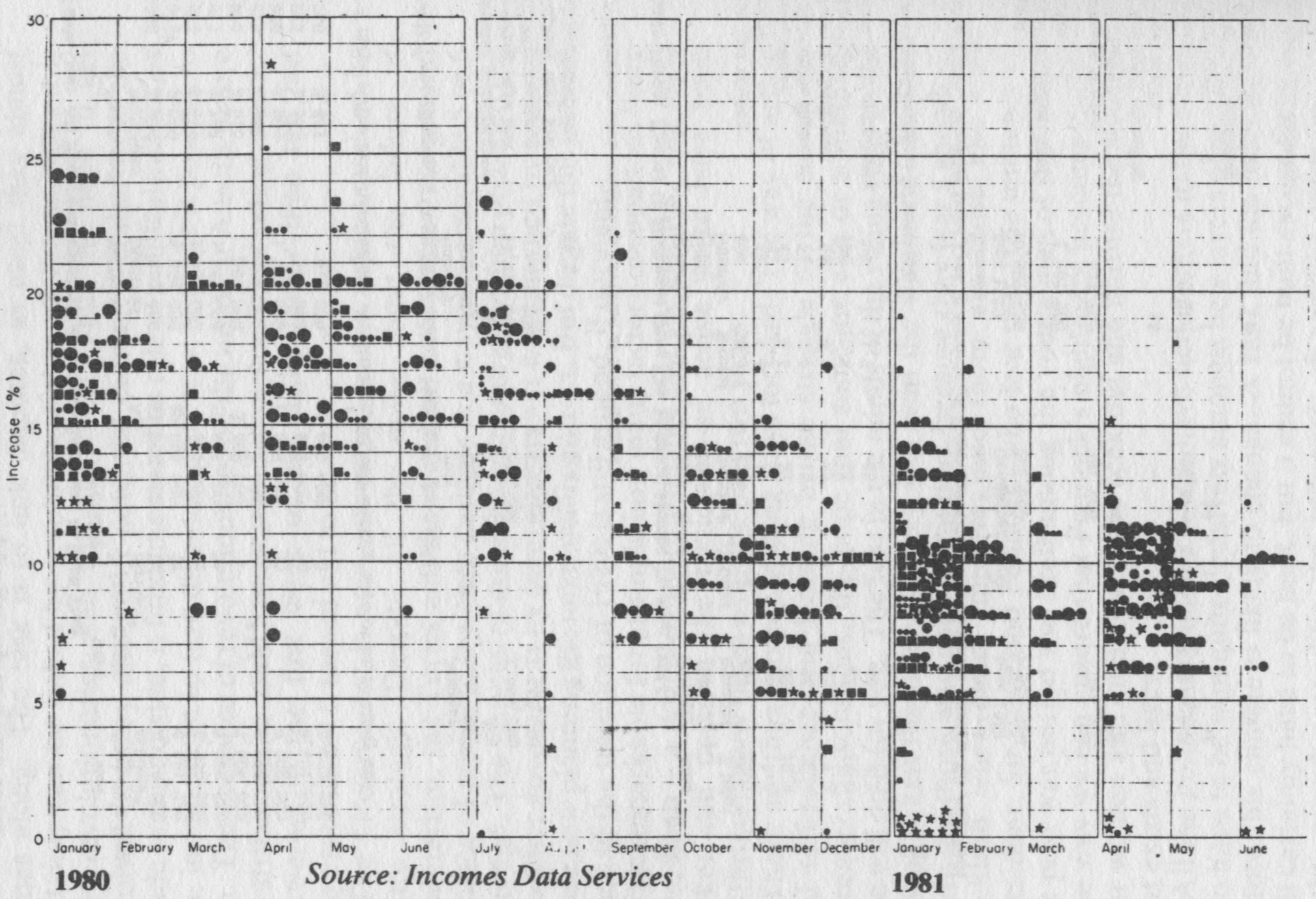

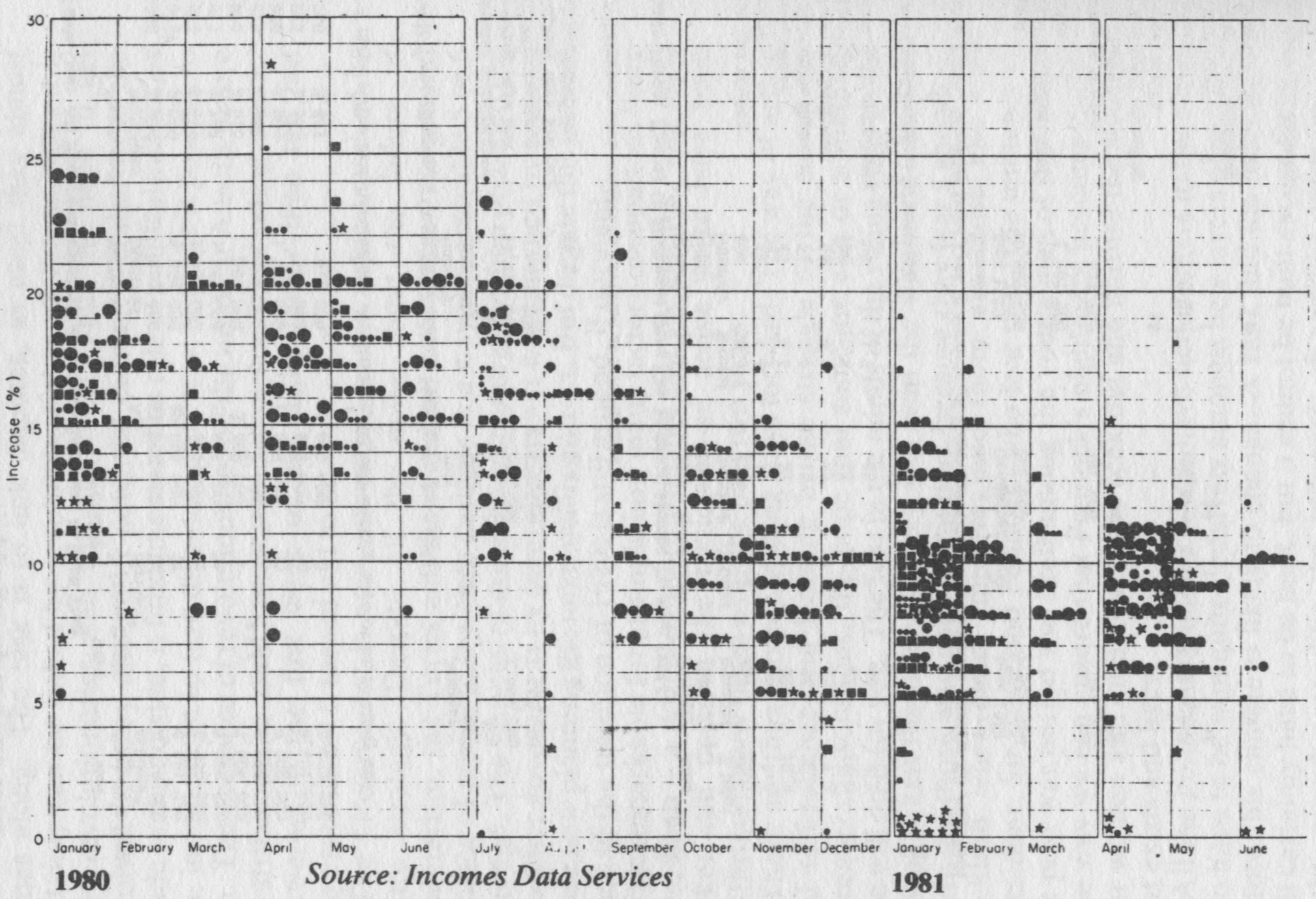

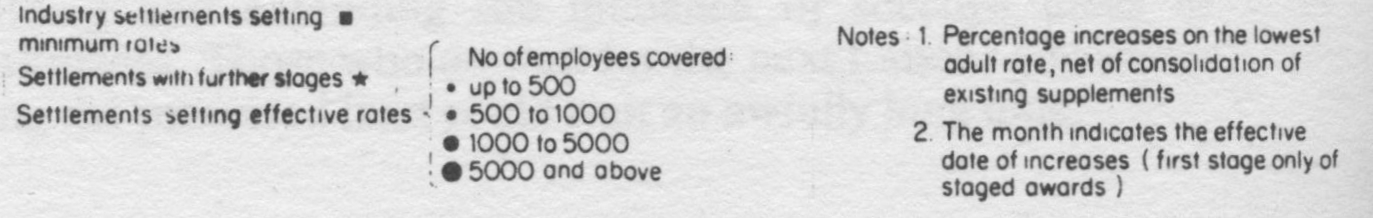

In a period dominated by the massive increase in unemployment, almost completely acquiesced to by the union leadership, there was a fantastic fragmentation of the struggle. A chart of pay increases on basic rates gives some idea of what happened, with workers on the whole keeping up with inflation in the early months of the Tory government but then increasingly finding it harder. This chart (see Appendix 2) makes several general points quite well:

As indicated above, it was the rate of increase in unemployment from the middle of 1980 – rather than the absolute numbers on the dole which was catastrophic. In percentage terms unemployment hovered around 5.5 or 6% throughout 1979. It first grew fairly slowly and then soared. The following table looks at selected industrial areas.

|

Unemployment % Rates: July 1979–June 1981 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

GB |

W. Mids |

S. East |

Scotland |

N. West |

North |

Wales |

|

July 1979 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

3.8 |

8.13 |

7.6 |

8.2 |

9.4 |

|

Jan 1980 |

6.0 |

5.7 |

3.9 |

9.0 |

7.6 |

9.1 |

8.4 |

|

Apr 1980 |

6.2 |

6.1 |

3.9 |

9.0 |

7.6 |

9.1 |

8.4 |

|

July 1980 |

7.7 |

8.5 |

4.7 |

10.5 |

9.9 |

11.6 |

10.8 |

|

Oct 1980 |

8.6 |

9.6 |

5.4 |

10.9 |

11.6 |

11.9 |

11.9 |

|

Jan 1981 |

9.8 |

11.4 |

6.4 |

12.7 |

12.1 |

13.8 |

13.4 |

|

Apr 1981 |

10.3 |

12.3 |

7.0 |

12.8 |

12.6 |

13.7 |

13.6 |

|

June 1981 |

10.9 |

13.2 |

7.3 |

13.5 |

13.5 |

14.9 |

13.9 |

|

Source: DE Gazette, August 1980/July 1981 |

|||||||

This table almost speaks for itself – but there are a number of very special developments which it hints at as well. One is that unemployment hit particularly hard in the Midlands (doubling in a year) and that the old areas of unemployment were no longer exceptional. This had major implications for the struggle on wages. Pay increases were in fact higher in the North East or Scotland, where the dole was not a ‘new’ threat, than in the West Midlands, where the number on the dole rose from 133,000 in January 1980 to 306,000 in June 1981. The pay struggle was largely determined by the speed and aggression with which the assault on jobs occurred. This ‘West Midlands factor’ has had an extraordinarily wide effect: it is tied in with the sacking of Derek Robinson, the emergence of Michael Edwardes as the bosses’ hero, and the propaganda campaigns on pay and jobs waged by the CBI, Engineering Employers’ Federation and government alike.

The second important point has been made before – the rapidity of the general rise in unemployment – and is merely re-emphasised by the table.

A third point, familiar to all readers of this journal, is that within these regional totals are some astronomic local unemployment figures. You no longer have to go to Northern Ireland to find 20% or 25% on the dole. The June 1981 unemployment rates showed: Corby 21.9%, Mexborough 20.6%; Consett 26.4%; Irvine 21.8%. There was nearly one in five on the dole in Oakengates, Birkenhead, Liverpool, Hartlepool, Teesside, Wearside, Bargoed, Ebbw Vale, Wrexham, Bathgate, Dunbarton, North Lanark.

In terms of trade union membership all this has had a drastic effect. One worker in six in manufacturing lost their job during this period. The AUEW’s membership, for example fell from 1,230,282 (the highest ever) at the end of 1979 to 1,182,408 12 months later and to 1,062,587 by mid-1981. The T&G’s membership fell from 2,086,281 at the end of 1979 to 1,886,971 at the end of 1980 (according to TUC statistical statements). In all the recorded membership of the TUC fell by 571,095 in one year, ‘the most significant decrease in our numbers since the 1920s’ as Len Murray put it on 6 September 1981.

The TUC figures are of course unreliable (the ISTC for example seems only to have lost 3,000 members in a period of huge steel cutbacks). They are also out of date. But nearly all unions lost members, and the AUEW figures, which are accurate and up to date, show a loss of 15.8% in 18 months. Only a few unions, for peculiar reasons, held their own or gained – NALGO and the NUJ are two contrasting examples. In the main, union membership has declined as those who have lost their jobs have left their union. The only serious example of people in employment leaving unions from choice is ASTMS, which lost members among foremen and supervisors in the West Midlands.

Loss of membership has had several effects on unions over the past two years. Several T&G regions have nearly been bankrupted for example. The National Graphical Association has had to levy members to pay unemployment benefit. All unions have been conducting cost-cutting exercises and have therefore looked askance at strikes and strike pay. At its most extreme, loss of membership and revenue has come out in the open with officials arguing against strikes, for example the notorious January 1981 letter from Brian Mathers, T&G Midlands Region secretary, to all regional officers, which called for ‘all possible alternatives to strike action to be considered’.

Before turning to a detailed look at what happened in different sectors and unions, the overall lack of generalisation of trade union struggles over the past two years needs to be stressed. This may seem a wrong notion – after all there have been several important disputes or near disputes since the Tories came to power – and indeed these have tended to be more successful than local struggles. But until the People’s March successfully detonated some small political stoppages, there was a tremendous vacuum of generalised struggle.

It need not have been so: the preparations for a Welsh general strike, at the beginning of 1980, when the steelworkers were out, had real support – until a combination of sabotage by the Wales TUC and bureaucratic assumptions of rank and file backing from the South Wales NUM saw the movement collapse. Similarly there was a widespread wave of solidarity with the South Wales miners when they finally did come out in February 1981 – not only in the NUM, but outside. But the climate of fear of action which was epitomised by the failed Day of Action on 14 May 1980 was much more typical.

The May 14 Day of Action, called by the TUC against government policy, merits separate consideration from other events over the past two years. It was the patchiness of the stoppages on May 14 that was above all typical. In Scotland there was a near general strike – in London hardly any big workplaces (except Fleet Street) closed, but a significant number of medium sized factories were out. There was a widespread backlash orchestrated by the press and television, but where the arguments were put firmly, for example at Gardners, the response was not too bad (50% came out). The major lesson to be drawn was that while the very traditional core areas of militancy did support the stoppage, there were a large number of ‘left’ led factories which did not even discuss the TUC call. On the whole few well-known workplaces were on strike (except in Scotland) – all sorts of smaller places came out. The public sector support for action was quite strong and the demonstrations were largely of public sector workers. This undoubtedly was partly because the tradition of one day stoppages between 1976 and 1979 was overwhelmingly public sector and there had been at least three mass demonstrations of public sector workers in the period. It was also the case that private employers put a lot of pressure on stewards and a lot of propaganda into their factories to get the action call disobeyed.

Apart from the climax of the People’s March and the May 14th events, the demonstrations on 9 March 1980 against the Employment Bill, and at the Tory Conference on 10 October 1980, were important. While the March 9th 1980 mobilisation was quite impressive – about 70,000 – it was far smaller and less militant than the great Industrial Relations Bill march in 1971 (the build up for the latter was of course entirely different, with one unofficial one day strike and two AUEW national stoppages against the Bill). October 10th 1980, apart from showing the pulling power of the Right to Work Campaign, also saw the degree to which the T&G, working on its own, could mobilise some impressive contingents. This was again seen in the demonstrations called by the Labour Party in Liverpool and Glasgow. These latter marches, in contrast to March 9th 1980, were far more determined in character, as was the mood of the crowd which greeted the People’s March. But a very obvious weakness of all these events was the size of contingents from single factories, pits, docks or other workplaces. It is hard to be accurate about these things, but in every case the maximum number mobilised from any single place seemed to be 10% or so. The demonstrations were of militant minorities, a crucial contrast with the early 1970s. On the Industrial Relations Act the AUEW above all was producing information for the shop floor at a tremendous rate. By contrast the last period has been notable for the reluctance of established militants to risk the arguments and knockbacks; this is why the failure of May 14th is so critical to an understanding of the state of the movement over the past two years.

Turning now to key industries, it is worth beginning with engineering and steel for a simple reason: both had major national stoppages; both were the biggest strikes ever (in terms of days on strike); both were ‘bad draws’ as far as the workers involved were concerned; and both have been followed by largely successful employers’ offensives on jobs and productivity.

First, engineering. The one and two day stoppages called by the Confed from August to October 1979 were much more widely supported than anyone – including the AUEW leadership -expected. Even now no one knows how many workers came out, or for how long: the DE figures say that there were 1.5 million workers involved and 16 million days ‘lost’ – which is simply an estimate. Equally, no one really understood at the time of the strike what it was really about. The Confed claim was centrally for an £80 rate for craftsmen, five weeks’ holiday and the 35-hour week. Eventually the settlement gave £73, the 39-hour week ... in 1981, 5 weeks’ holiday ... in 1983, and broke the link between factory wage negotiations and national increases. The latter move was the single greatest prize for the engineering employers – they had been trying to break this link for more than a decade. But the price the EEF paid was quite a heavy one, especially in retrospect; throughout the ensuing recession the employers have had to give away more than they wanted on conditions. They have not succeeded in extracting a high productivity price for the one hour cut in the working week, and in general the EEF has less authority now than it did in 1979. We shall examine these problems on the employers’ side in more detail when we come to consider the state of their organisation later in this article.

The national engineering stoppage was characterised first of all by passive support. There was very little scabbing on the one-day strikes, and in fact by the third week they had gained support. Nevertheless, there was little or no propaganda work done by the union – right or left – stewards were left with very little to go on, and to fend for themselves. For example, in the fourth week of the dispute the original leaflets backing the claim could be seen lining the corridors in the Manchester AUEW office! Meanwhile the employers pumped in a lot of propaganda on the strike, chiefly along the lines that there was no point in striking for a higher national minimum rate, because it didn’t apply to anyone. This was a view widely shared among militants, in the broad left and elsewhere. In fact, it was not true. Some were more concerned about conceding a big increase (especially on the semi-skilled rate) than about the cut in hours, which Duffy was to claim as the big breakthrough (it was – but for those who came after, rather than the engineers). The concern about the semi-skilled rate was that a high national minimum would erode productivity bonuses, especially in light engineering with large numbers of women employed on basic rates only a few pounds above the minimum. Even the poor deal the unions settled for had this effect: for example, the value of the increase on money at Ferranti was about 2.3% on average, before the factory wage negotiations started.

The one day strike calls were succeeded not with a real escalation but with a two-day strike call. This began to undermine the stoppage and allowed the Confed leadership to claim in retrospect that the members were not behind the strike. Though this was partly true, the real reason was that the two-day strikes kept the members in isolation for four successive days, between Friday and Wednesday. The result was increasing uncertainty about support: some BL plants went back, some other militant factories, like Trico in West London, petitioned to go back. There was a backlash which the press was able to use. But the employers attempt to put the pressure on with lock outs backfired. The lock outs were widespread. Rolls Royce was the most prominent firm, but in all there were 108 lock outs in the last week of the dispute (typically, the issue of whether these members should be paid for the two days stoppage that week, as well as the three days’ lock out was only settled by the 1980 AUEW Final Appeals Court. In January 1981, Sir John Boyd announced that the payment of this additional benefit would be made ‘early this year as and when the money is available’).

The problem with the final settlement of what was probably the most important dispute in the two years since Thatcher’s election is that it was a sell out on pay and on the 35-hour week, and gave very little to well-organised plants for two years – and at the same time it did give pay increases to the poorly organised plants and allowed Duffy to claim, incontrovertibly, that he was the first union leader to negotiate a national agreement giving 5 weeks’ holiday and less than 40 hours. The left in the AUEW was not able to make any criticisms stick and this was certainly one of the reasons for the dismal showing by Bob Wright in the presidential elections at the end of 1980. The result gave Duffy an unprecedented first round ballot victory, with 126,135 votes to 58,826 (the only other candidate with any significant backing being Roy Frazer, with 14,748 votes, presumably almost entirely from tool makers). The result showed the absence of any great support for Duffy, but the complete bankruptcy of the old left: in terms of the candidate, his campaign, and a rank-and-file critique of the union leadership. It was a crushing blow for the left, because it came after some appalling behaviour by the leadership. The sell out on the national claim was rapidly followed by the successful sacking of Derek Robinson, the Longbridge convenor, which could not have been carried through without the connivance of the AUEW executive in calling off the initial strikes which backed Robinson. About 57,000 BL workers came out after he was sacked (and two other senior stewards given final warnings) for the publication of a BL combine pamphlet opposing the Edwardes ‘rescue’ plan. BL is examined in detail in a later section on carworkers – the important thing as far as the AUEW involvement went was that the executive called an official inquiry into the affair and called off the initial solidarity strike. From that point on there was little or no chance of any action, and when the final issue was put to a mass meeting three months later, there was a virtual lynch mob atmosphere against Robinson, with only the stewards and a few militants supporting a strike. It would be hard to estimate the impact of the Robinson affair on AUEW stewards organisation. Already in a weak position, stewards knew they would be lucky to get official backing- and that when it came it might take the form of a disguised stab in the back. There were also a host of engineering employers who wanted to put the boot in in the wake of what they thought was an unnecessary compromise in the national dispute.

There was thus a drop in the number of engineering stoppages (which were in any case at a pretty low level already). Unofficial strikes were either very short or almost non-existent. There was a very uneasy climate, influenced heavily by the press coverage of BL and the fact that long strikes at Talbot and Vauxhall were both defeated.

A look at AUEW official strikes shows what happened after the national dispute:

|

AUEW Official Disputes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

4/79** |

1/80** |

2/80 |

3/80 |

4/80 |

1/81 |

2/87 |

|

Wage claims |

25 |

16 |

12 |

7 |

10 |

12 |

14 |

|

Redundancy |

3 |

2 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

8 |

10 |

|

Victimisation etc. |

3 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

|

Offensive* |

15 |

9 |

11 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

7 |

|

Defensive* |

12 |

9 |

20 |

10 |

20 |

15 |

14 |

|

TOTAL DISPUTES |

45 |

36 |

51 |

21 |

36 |

26 |

32 |

|

* where known |

|||||||

|

(Note: These columns do not add up because the ‘offensive’ and ‘defensive’ disputes include those in the three other categories. There is what the AUEW Journal discretely describes as ‘a time-lag’ between strikes occurring and payment being made for the strike [which is what the above figures represent]. There also some double counting in these figures. |

|||||||

The figures should not be interpreted too literally. A lot of the disputes listed involved very few people: sometimes one. In the first two quarters of 1981 for example the number of AUEW members getting strike benefit totalled 8,763 (of whom 2,333 were involved in a five-day strike at Automotive Products). But if the figures are taken to indicate the general trend in engineering they are useful. A greater and greater proportion of strikes have been defensive. Fewer and fewer engineering workers have been prepared to fight on wages. As we shall see later on when looking at the complete official strike statistics (Appendix 1), the number connected with pay fell to under half between July 1980 and June 1981.

Some other evidence on engineering, this time for 1979, was gathered from official statistics and published in the journal Incomes Data Report, It concerns what the DE calls ‘prominent’ stoppages – those that account for 5,000 or more working days on strike. Once again the data show the way in which the struggle became defensive, particularly in the car industry:

|

Causes of prominent industrial disputes in 1979 |

||||

|

|

Number of |

Workers Involved |

Working |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

directly |

indirectly |

|||

|

Pay claim/offer |

|

|||

|

Motor vehicles |

7 |

16,670 |

1,650 |

680,800 |

|

Mechanical eng. |

16 |

11,735 |

1,050 |

316,000 |

|

Electrical eng. |

15 |

18,275 |

3,610 |

677,500 |

|

Pay and conditions |

|

|||

|

Motor vehicles |

12 |

31,380 |

22,155 |

355,700 |

|

Mechanical eng. |

9 |

5,540 |

3,470 |

136,000 |

|

Electrical eng. |

6 |

4,575 |

3,785 |

10,100 |

|

Disciplinary/ |

|

|||

|

Motor vehicles |

12 |

63,545 |

16,885 |

369,200 |

|

Mechanical eng. |

1 |

430 |

– |

34,400 |

|

Electrical eng. |

5 |

4,230 |

555 |

32,700 |

|

Redundancies/ |

|

|||

|

Motor vehicles |

2 |

1,335 |

– |

45,500 |

|

Mechanical eng. |

4 |

2,185 |

– |

71,200 |

|

Electrical eng. |

1 |

5,000 |

– |

7,500 |

|

All disputes |

|

|||

|

Motor vehicles |

33 |

112,930 |

40,690 |

1,451,200 |

|

Mechanical eng. |

30 |

19,890 |

4,520 |

557,600 |

|

Electrical eng. |

27 |

32,080 |

7,950 |

727,800 |

|

Source: DE Gazette, August 1980 |

||||

Despite the aftermath of the national dispute, the enormous recession in the industry which saw one in six workers made redundant and the confirmation of the move to the right, there were some hopeful developments. The three big Manchester engineering strikes – Adamsons, Gardners and most recently Lawrence Scott – all pointed to the fact that there was still a bedrock of militancy, at least in the North West. The Gardners occupation most importantly had a galvanising effect: there were several more occupations in its wake and it seemed to prove that you could fight closures. Though, as Mike Brightman pointed out to Socialist Review at the time, unlike the Massey Ferguson occupation in Liverpool which collapsed in isolation in the summer of 1980, Gardners was not a closure – it was a ruthless attempt at rationalisation which came unstuck. One of the important things about the three Manchester disputes was that all three consciously related to each other, particularly as regards getting outside support. Part of the result of the low tide of militancy was to make the network of militants that does exist that much more apparent.

While Manchester preserved its reputation for resistance, the Sheffield disputes that occurred in early 1981 had real problems. Partly this was a result of the poor performance of the engineering broad left in the area, which had ducked its responsibilities in the steel strike a year earlier and was then faced with a series of disputes provoked by management at three tool plants: Snows, Plansee and Eclipse. The disputes happened to coincide with other cases of victimisation and suspension at Markham in Chesterfield and at Canning Town Glass (an AUEW maintenance strike). What characterised these South Yorkshire disputes was that as in Manchester they were part of a general employers’ offensive, as in Manchester they were winnable disputes, but in Sheffield the strikes were separated and isolated from one another. Though it was again the AUEW executive which smashed Plansee, which lasted much longer than the other strikes, the level of local support was far more sluggish, and there was less consciousness or desire to make the strikes a focus and take the issues outside the immediate factories involved. Again a case of fragmentation leading to defeat.

Manchester and Sheffield were not typical. Elsewhere such strikes as there have been were smashed with monotonous regularity. For example at Kearney Trecker Marwin, part of Vickers, in Brighton the management provoked a two-week strike over wages which culminated in sackings and victimisation. At Priestmans in Hull (like Adamsons part of the Acrow group) a long strike against a wage freeze was badly defeated, with the company winning on jobs as well as pay. At Birmetals in Birmingham, the unions left their members high and dry in a dispute that was a preview of the sell out at Ansells.

The steel strike and its aftermath is much more simple to relate than engineering, chiefly because steel industry management (ie BSC) has approached its task with the straightforward aim of slashing the workforce and dividing it. The steel strike began on 2 January 1980 and ended just 13 weeks later. The initial BSC offer of 2% (in fact not even that) was replaced by a 15.5% deal – with a major productivity element. This was the first ever national steel strike and, despite the intentions of steel union leaders, especially Bill Sirs of the ISTC, it involved solidarity from the private sector, support from other workers, mass pickets, a government crisis and the possibility for a time of a general strike in Wales.

Unlike the engineering stoppages, the steel strike was an active struggle. Independent pickets and strike committees were formed in the most militant area – South Yorkshire – and despite attempts by Sirs and other union leaders to agree to a capitulation early on in the strike, it took a committee of inquiry and a final stab in the back from the TGWU (which turned down calls for a national dock strike in support of the steelworkers) to settle the dispute on terms the Tories could live with. The full chronology of the strike was given in the April/May 1980 edition of Socialist Review, together with an analysis of the way in which potential solidarity with the steelworkers was frustrated until far too late by the TGWU officials, whose support could have won a crushing victory over the Government in six weeks.

The steel strike nearly broke the Tories. In his informative book Mrs Thatcher’s First Year, the editor of the Times Business News, Hugh Stephenson, describes how the Tories and employers were both split on how to handle the mass picketing of private steelworks – particularly in Sheffield, where the mass picket of Hadfields caused the plant to shut down on police advice in the first week in February. Despite the fact that Hadfields workers voted to go back they were picketed out again four days later. There was a public split between Prior, the employment secretary, who wanted the police to deal with pickets, and Howe, the Chancellor, who declared ‘It would be fatal to Britain’s chances if this government lost its nerve and neglected its clear duty to take in hand the necessary reform of the law.’ Prior had already stated on January 30th that there would be new rules on secondary strikes in the new Employment Act, and this was one reason why the union leadership made every effort to limit picketing and weaken solidarity.

For all the picketing and the government crisis there was a weakness in the strike that was only partly the result of bureaucratic sabotage. The dockers failed to respond to the very serious threat to their jobs represented by the import of scab steel through unregistered ports; in London, there was a considerable amount of steel coming in through riverside wharves. Eventually – on 23 March 1980 – Liverpool dockers came out 100% (together with other portworkers) against the threat to suspend 100 men for refusing to load steel onto a Russian ship. But this was a mere nine days before the strike ended. Similarly delegations from London and an eventual appeal from T&G national officer Ron Todd persuaded Ipswich dockers to black steel on March 27th – four days before the settlement.

The other weakness was in engineering, particularly of local left leadership. As we wrote in Socialist Review (April 1980) of the Sheffield broad left, which was in the storm centre of the strike,

‘From the outset there was no campaign – neither by the Sheffield Confed collectively, nor by any of the member unions, to carry through the (blacking) decision ... Some of the really well organised factories did implement the blacking (e.g. Shardlows, Keetons and Easterbrooks) ... Unfortunately these excellent examples were not the general picture in Sheffield. Many stewards went to mass meetings to argue for the blacking, but in the absence of any lead from the officials who had voted for the policy, they failed to win majority support.’

Despite this weakness, 14 Sheffield factories did shut down in the tenth week of the strike, when T&G members respected picket lines in line with a policy vote by a city-wide stewards meeting. This meeting had agreed to follow the belated T&G instruction for no crossing of picket lines – two months after the strike began. But this fine show of solidarity collapsed in the face of isolation.

Isolation was the third crucial weakness in the strike – evident at the time and more so in retrospect. It may seem odd to talk in these terms in view of the tremendous Sheffield experience and the one-day regional strike in South Wales on January 28th- not to mention the mass pickets, general strike possibilities etc. But the strike was remarkably passive in Wales, considering the enormous local support. There were very few Welsh flying pickets. In the Midlands, the crucial area for affecting engineering and hence achieving the decisive pressure on the Government there was always a lack of coordination, a major division between the Sheffield pickets and the local steelworkers, and, fundamentally, a lack of numbers to cover industry. There was fantastic solidarity shown by the T&G drivers’ branches at the Birmingham Container base and in Wolverhampton and West Bromwich, and some good support in one or two factories. The fact that we know of the cases unfortunately proves the argument about isolation. There was a great deal of verbal support and considerable financial support, but hardly any other groups of workers were prepared to take the necessary risks which were required to give effective practical backing to the strike. The abstention or obstruction of district or regional T&G officers was then decisive in weakening solidarity moves. What could have happened was shown when a Birmingham steel stockholder secured an injunction against British Rail to release 500 tons of steel. Regional official Brian Mathers (the hero of Ansells) issued an instruction enforcing blacking. NUR drivers moved it, but refused to cross a T&G picket line, and finally T&G members inside the stockholding company itself refused to handle it.

The aftermath of the strike has been extremely demoralising. Though the militants went back to work reluctantly and promptly blacked scab lorry firms in defiance of official union policy, BSC almost immediately began to embark on its plan of wholesale closure, employing very clever divide and rule tactics. In South Wales for example there has been massive job loss at both Llanwern and Port Talbot, huge increases in productivity and, under the new BSC chairman, Macgregor, the implementation of low manning/ high wage agreements in the interests of viability. Wage differentials between the areas have opened up even more than in the past, with BSC’s successful six-month freeze on national pay increases to mid-1981 going through virtually unopposed because of high local productivity payments. The area divisions which were endemic before the strike, but seemed to have been broken down, have reasserted themselves. Just as serious, private sector steelworkers, like those at Hadfields, have been carved up by special marketing and production deals between BSC and the largest private firm, GKN. In percentage terms the job loss in the smaller private firms has been more serious than in BSC – with private sector workers who supported the ISTC’s call for solidarity in 1980 suffering the worst in the 1981 recession.

The similarity between engineering and steel over the past two years was noted earlier. It extends in a very modest way to the way in which revolutionaries have organised since the national strikes in the two industries. In steel the successful defence of Real Steel News against a witch-hunt in the ISTC and in engineering the flow of resolutions against the betrayal of Derek Robinson and the sell out at Laurence Scott show that there is some possibility of a response to the entrenched right wing that exists in both the ISTC and the AUEW. But this has not extended so far to winning more than isolated victories against bureaucracies whose conservatism has been enormously reinforced by the depression in industry. This has been as true in the car industry and in a series of general disputes in which the TGWU has been involved, as in engineering and steel, as the next two sections describe.

The balance of forces in the car industry has, more than in any other industry, tilted towards management. What happened at BL, with the victimisation of Derek Robinson, the imposition of the 92-page ‘slaves charter’ and a five per cent wage increase is only one part of the story – the most well-known.

The employers were already well on the offensive in the car plants, as in engineering, before the Tory election victory in 1979 (see for example The Ruling Class Offensive, D. Beecham in International Socialism 2 : 7, Winter 1980). The big Vauxhall and Talbot strikes in the late summer of 1979 were both defeated. They were long and bitter battles which seriously eroded union organisation in the plants concerned (for different reasons Vauxhall Luton and Talbot Linwood were not involved). This was the first major defeat for the shop floor in the car industry for many years. It was in fact at Talbot that management had its first big success in imposing a pay increase way below the inflation rate – and at Ellesmere Port Vauxhall management imposed their own efficiency document, which was much shorter than 92 pages but almost as nasty as the Edwardes plan.

Nevertheless BL, Longbridge especially, represent the most serious defeats. In the aftermath of the Robinson victimisation the company could have got away with a lot more than it did. There was a high turnover of stewards, management imposed the slaves charter and was able to sack more stewards after the November 1980 ‘riot’. Workers were shifted from area to area in an unheard of manner, the grading appeals were put into procedure and disappeared. At Longbridge there was very widespread demoralisation; it was ‘catatonic’ in the words of one steward.

In other plants it was a bit different. A total of 18,500 BL workers came out in April 1980 against the imposition of the new productivity conditions and grading structure. The strike’s potential was enormous, with different plants coming out for different reasons, but all united against Edwardes. The strike was scuppered by a completely abject and unexpected cave-in from the T&G, which had up till then being making loud noises about how it would have fought to save Robinson’s job etc. The apparent lesson of this strike (apart from the T&G’s treachery) was that the action was stronger and more wholehearted in the smaller, ‘moderate’, BL plants. That this worried BL was shown by the way in which Edwardes had to make a hurried and undignified return from South Africa. While the traditionally ‘militant’ works – Longbridge, Cowley, Rover – were either still at work or completely passive, the Common Lane and Tyseley factories, both relatively small, launched themselves into the struggle with enormous zest. Common Lane put pickets on the neighbouring Drews Lane factory – another base of the old combine committee – and got the T&G stewards to black all internal transport. At Tyseley the stewards committee, which had been working unobtrusively to create shop floor unity for the past two or three years, organised a model strike. The strike committee met every morning, they put proposals to a meeting of all the pickets. It was the first time in some seven or eight years that the 1,500 workers had been on strike.

The collapse of the resistance to the management offensive was on this occasion entirely the result of officials pulling the plug on their members. And immediately BL management had got Moss Evan’s agreement to the implementation of the 92-page document, they took their first real offensive action at Longbridge. There was a partial and very militant stoppage which tragically remained isolated in one area of the plant and ended in a shabby compromise. The end result was a further serious setback for resistance to management control: but it showed that resistance was still there on a wide scale. It is important to keep in mind the numbers that came out when we talk about the collapse of militancy in the car industry. Some 57,000 when Robinson was sacked; 18,500 against the slaves charter. One further point was that by and large it was different sets of workers taking action on the two occasions. On both occasions for all the Edwardes bravado the company could not have won without the direct and conscious retreat of the trade union leadership – first the AUEW right-wing and then the TGWU ‘lefts’.

Moving on to the events of late 1980 at Longbridge, the remarkable fact is that the workforce threw out the company’s 6% pay offer in a mood of confidence that the new Metro model provided the company with success and the shop-floor with a bargaining counter for the first time in two years. By this stage management had begun to impose the new working practices it demanded with a vengeance, partly through de-manning – abolishing relief workers for example – and partly through employing the hardest supervision on the key lines, such as the Metro. But far from the Metro lines being worked by loyal robots, as the company had originally intended, it had become one of the most militant sections in Longbridge. Those sporadic stoppages which have occurred – a tiny fraction of past disputes – have nearly all been in the ‘successful’ parts of BL. This has considerable parallels in the struggles elsewhere in the car industry – at Ford Halewood and Talbot.

At Ford management moved to impose a new discipline procedure against unofficial stoppages at the end of 1980. It was distinguished by being ‘negotiated via a letter announcing the new policy of suspensions without pay to the home of every Ford manual worker. Initially there was no resistance. Halewood had strikes in early February 1981 on safety issues during which the company implemented its policy of suspending whole shifts without pay – they lasted three days and were defeated. But then on 8 May Halewood stopped totally and indefinitely against the discipline code (it coincided with a strike by 3,000 Longbridge workers over increased output targets). The Halewood strike ended after 13 days with what, in terms of the car industry and in terms of the management offensive of 1980/81, was a victory. The code was withdrawn completely in return for a T&G commitment to avoid ‘unconstitutional’ stoppages. The stewards did not, however, undertake to be shop-floor policemen. Instead, the Halewood stewards seem to have been able to retain a substantial degree of control.

The similarity with the upturn in confidence at Longbridge after the Metro sold well (and at Cowley after a return to five-day working) is that Halewood has just had substantial investment in new plant. The faults in the new equipment caused a lot of irritation and friction between shopfloor and plant management – but its arrival seems to have boosted the confidence of Halewood workers to win a fight.

A much less spectacular example of this was at Talbot Stoke in Coventry. Here, a long period of short-time working had sapped confidence and fragmented the workforce. Exaggerating the problem slightly, deputy TGWU Convenor at Stoke, Gerry Jones, said that he felt he had not seen the members who elected him for a year – and that the only time he was at work they held stewards’ meetings. In essence the isolation of stewards from the members was total – the only contact was at social events. This has been a general side-effect of short-time which we shall look at again in the conclusions to this article. At Talbot, however, the return to five-day working in early summer 1981 produced a very rapid turn-round – so much so that the stewards felt confident enough to push for and win some 20 extra jobs in the factory. The long period of retreat and isolation does not seem to have done great permanent harm to organisation.

The event in Talbot with the greatest significance was, however, the vote to accept the closure of Linwood. Like the Robinson affair, this could have been a key turning point. The issue came to a head just before the People’s March campaigning got under way; and the existence of a militant, political workers’ fight against closure at that time would have resulted in a much harder and more potent campaign against unemployment that in fact occurred. The TUC’s smothering influence would have been much easier to resist.

The failure to fight at Linwood was debated in depth at an SWP national committee meeting which was reported in detail in the April 1981 issue of Socialist Review. Its conclusions could be summarised thus: that one third of the plant was ready for a militant fight; that the erosion of stewards’ power in car plants meant a fatalism crept into the rank and file; that the difference between Gardners and Linwood was that Gardners retained the piecework tradition and therefore sectional strength; that the legacy of past acceptance of redundancies and of the stewards committee not backing sectional fights finally caught up with the factory leadership. All these factors were present at Linwood and we can add one more – the fact that unlike Gardners, or Ansells, or Laurence Scott this was a fight which felt impossible. The vote to fight at Gardners – where management was keen to keep the plant -was after all quite narrow (a fact we sometimes forget). The problem at Linwood was perhaps that the militant minority found it impossible to win the psychological argument that it was possible to take on Peugot and the Government and win.

Thus far we have looked at three crucial industrial sectors involving essentially three unions. Turning the spotlight onto the largest, the TGWU, is a useful way of dealing with a number of very important setbacks suffered over the past two years. Let us summarise them:

No doubt this list can be extended! The point of this chamber of horrors is not so much that it shows the appalling performance of T&G officialdom at every level (which should be fairly familiar to readers of Socialist Review and Socialist Worker) – but rather that it shows that the officials have more or less had it their own way. The T&G full-timers have been pretty weak in opposition to the employers – but rather more successful against the union’s militants. Ansells was sold out miserably by Brian Mathers and other Region 5 officers. But there was a great void at rank and file level in organising support. Workers at the Ind Coope Burton brewery were in fact on overtime during the strike and received a handsome £10 a week pay increase as soon as it was over. The Ansells workers could not secure the necessary unofficial blacking; contrast this with Lee Jeans, where official docks blacking was straightforward. Again, in the car industry, Moss Evans’ agreement to the Edwardes plan caused the complete collapse of the strike at BL (though some votes were split down the middle) – there was no network of militants to resist.

The impression is overwhelming. The isolation of different regions, trade groups and factories within the union has increased. As power at the top of the union has declined – with Jack Jones’s departure and Moss Evan’s illness – a new generation of national and regional officials has been exerting authority. Some of these officials are ‘left’, others ‘right’. This is almost entirely irrelevant. Brian Mathers in Birmingham and Hugh Wyper in Scotland have behaved in an almost identical manner – and succeeded in defeating and isolating strikes where the employers were impotent. Despite the emergence of a ‘new’ broad left in the union, which has come into conflict politically with leading old left officials like Kitson, there has been no translation of this into practical activity on the ground.

It would be dangerous to generalise too much from the T&G to other unions – the new broad left in the Post Office is far more grassroots oriented for example. Nevertheless the picture of a political upturn in the unions during the downturn in the shop-floor struggle does not appear to be translating back into a network of likeminded militants on the ground. In the TGWU, because of the fantastically divisive nature of the union’s structure, this fragmentation means that the new left can be easily sucked into the machine.

The miners remain one of the very few groups – with the dockers and sections of the print – to have resisted the employers’ onslaught. The story can be very simply be told: the Tories have deliberately avoided taking on the NUM. On the one occasion when the conflict erupted – over the Coal Board’s pit closure list in February 1981 – the Tories moved with positively indecent haste to announce extra aid for the industry. The miners won the battle, of course, but not necessarily the war. What came out of that particular episode was that the divisive nature of the miners’ productivity scheme – with different pits and areas on different wages – has not seriously weakened solidarity at a national level. The proposed closures were admittedly in various mining areas but it was South Wales which was seriously affected and it was from there that the flying pickets were organised. The contrast with the events 12 months previously, when the Welsh NUM members overturned a previous strike decision, was extreme. With some of the least militant pits coming out first and picketing of power stations starting immediately, the action was in fact more determined than in the two national stoppages of 1972 and 1974. As the Financial Times stated on 19 February 1981:

‘The movement of all coal from pitheads was at a standstill in the region. Train drivers were refusing to cross picket lines and coal merchants were unable to pick up domestic supplies from colliery stockyards. Steelworkers were being picketed in the first 24 hours of a dispute that lasted all of five days.’

A total of around 50,000 miners came out. The absence of clear-cut support from Arthur Scargill was a notable feature of the dispute, despite the fact that Yorkshire had already voted to strike in the event of closures: two pits, Kellingley and Park Hill, came out immediately. Even the Durham miners affected by the closure threat came out and organised their own pickets, in an NUM area known for conservatism. Scotland also came out solidly.

The main difference in South Wales compared with the events of 12 months before was that nothing had been assumed, delegate meetings had been held, a network of militants re-established in the wake of the previous debacle.

The picture in the NUM on other fronts has also been less bleak than elsewhere. Not only have reasonable rises been achieved, without any further productivity concessions, but the votes against pay offers two years in succession have been around the 40% mark. The NUM was also one of the few unions that produced a sizeable strike on the 14 May 1980 Day of Action. The most encouraging development, however, must remain the fact that several years after a deliberately divisive productivity deal was pushed through by the Labour government and the NUM right wing, the fragmentary tendency that exists within the NUM does not appear to have broken the solidarity of the 1970s. Kellingley Colliery in Yorkshire which came out against the closures is one of the newest and highest-paying pits in the country; it is also Yorkshire’s largest coal producer.

General printing workers won the single largest victory over the employers to have occurred in the past two years – in fact one of the most crushing ever. A measure of the NGA’s success was that the British Printing Industries Federation, the employers, conducted their own independent inquiry into their defeat. It concluded that all the BPIF’s officers should be sacked.

This success by print craftsmen – at the same time as an important victory by journalists against lock out tactics by the world’s largest publishing firm, IPC – run counter to the general picture in the print, however. This was particularly the case in Fleet Street, where there has been continual job loss and where the Evening News closed without a murmur. One of the few bright spots in Fleet Street gloom was, oddly enough, the May 14th strike. NATSOPA decided to defy an injunction by Express Newspapers over the strike call. The company backed off completely in London – and suffered the humiliation of losing the next day’s production because it had produced a small scab edition in Manchester. The strike saw a large picket outside the Express offices (led by the evergreen Mr Reg Brady, who latterly moved from the Times machine room to being the Times’ industrial relations officer).

But the BPIF victory aside, the print crisis has grown rapidly. There were in any case specific weaknesses on the employers’ side in the BPIF dispute. Rather more typically, the recent restructuring of the BPC group by Robert Maxwell has seen the print unions grovelling to get agreements cutting ‘only some jobs’ and introducing pay freezes. At the Radio Times in Park Royal, for example (one of the best-organised factories in the country) it was only the obstinacy of a SOGAT chapel over the transfer of work to Scotland which led to any attempt to renegotiate the company’s takeover terms. One third of the jobs in the factory have been lost in any case.

The print unions have been dominated more than probably any other group by the financial crisis and the need for amalgamation to preserve union strength. Events have advanced rapidly. The NGA seems certain to take over the much smaller craft union, SLADE. The NGA is having unity talks with the NUJ. SOGAT and NATSOPA are also negotiating about unity. Instead of five unions, there may soon be two; one ‘craft’, one general. But these amalgamations are all taking place at a highly bureaucratic level at the moment, and there has been little experience of rank and file unity on the ground. One occasion when it did happen was in the long-running Camden Journal dispute, when NGA chapel officers at the Nuneaton printers established close relations with NUJ militants.

The NUJ itself is the odd one out in the print. It continued to fight small bitter disputes on jobs and on London weighting, its membership actually grew, postal ballot results showed a move to the left. It was also involved in one of the two print industry disputes – IPC and the BPIF – which caused a major reappraisal of the concept of employer solidarity on the management side (we shall examine the employers’ offensive below).

The public sector services have faced the brunt of the Government’s pay offensive. After the long overdue Clegg awards and other comparability increases during 1979/80, they were screwed down with a cash limit of 6% – now succeeded by a 4% policy. In the main there was very little overt opposition to this policy in the sectors where it mattered such as the councils and the health service. The ambulance workers caved in after initially showing that the rank and file stewards organisation established in the previous dispute is capable of organising independently of the full-time officials. In the NHS only the hospital electricians fought their way round the edge of the policy.

The other group of manual workers that was prepared to fight was the firemen. The immediate threat of action when they were offered 6% proved yet again – as with the miners, dockers and seamen -that a national stand against the Government stood quite a good chance of success. So the FBU retained its pay formula and got a total increase of 18.5% rather than the 6% the Government wanted.

There were, however, two ‘national’ public sector battles. The first involved NALGO’s comparability claim in the early part of 1980 (during the steel strike). The impact of this selective strike was twofold. First of all it was the first ever nationwide action by council white-collar workers; secondly it showed that NALGO is effectively two unions (at least). The mass of low-paid clerical membership (such as the Liverpool typists who have taken action this year on grading) carried the dispute: the image of NALGO that is often presented is, however, of local government officers, and it tends to be from these higher ranks that the left recruits and the union leadership is drawn. The terms of settlement would bring a wry smile to the lips of the average NUT member, who faced the same problem of a comparability award restoring massive differentials for the highest grade. The NALGO agreement in fact gave £189 at the bottom of the scales and £1,716 at the top. Despite the poor deal for the most important section of the membership, the dispute showed a lot of local initiative and as Phil Jones wrote in the April 1980 Socialist Review ‘In areas with strong shop stewards committees, particularly in the metropolitan areas, the industrial action committees were quite effective.’ On the other hand ‘ The effectiveness of the action was partial and a huge number of members were hardly involved.’

The latter statement could be the epitaph for the long-drawn out and bitter civil service dispute 13 months later. It is not yet possible to draw up a balance sheet of this action, though judged by any objective standards the course of action undertaken by the Council Civil Service Unions could provoke a huge backlash among the membership. But other than the national one-day strike and the huge walk-outs by upwards of 250,000 civil servants in protest against suspensions and scabbing there were only 5,000 staff actually involved in the dispute, often in tiny isolated units with little sense of support. So refined and subtle were the unions’ tactics to hurt the Government that they ‘forgot’ to involve their members. In view of this crazy strategy, the voting at the end of strike was remarkable, with the tax union, the IRSF, actually voting for all out strike action and the best-organised sections of the other main unions voting the same way.

Generally we can say that while workers’ organisation took a battering and union membership declined, while unemployment soared to 3 million and there were a further million on short time, the employers found themselves in the strongest position for many decades, certainly since the early 1930s. The question we really have to ask is: why was the offensive muted, and did it in fact take a more subtle form than the union-bashing of Edwardes and the Government?

Reviewing the employers’ attitude to the return of the Tories in a hard-line monetarist mould is like stepping back into a different world. The first CBI conference after the election was crammed with praise for the free market, calls for Thatcher to set business free and talk of employer solidarity and the balance of forces. A year later, in November 1980, new CBI director-general Sir Terence Beckett was to make his famous ‘bare knuckles’ speech -this time referring to the need to shift the Government away from its hard-line stance. At that conference there was hardly a whiff of union-bashing. Instead there were calls for lower interest rates, subsidised energy, measures to help the unemployed, moves towards import controls – in short a complete switch of emphasis. The difference was the onset of the recession.

But we need to be careful in summarising the change in the employers’ side. It is not a simple picture, any more than our side of the class war is. The latest round of pressure for more laws on strikes and the closed shop, for example, has seen most employers’ organisations argue for tougher measures. But the Engineering Employers’ Federation, traditional hawks, took a much softer line than most. The EEF said for example that ‘collective agreements should not compulsorily be made legally enforceable’ (the 1979 CBI conference voted that they should); the EEF said no special action should be taken against ‘industrial action or peaceful picketing where a strike is causing acute harm to the community;’ and the document also took a very cautious line on the closed shop. The areas where the EEF wanted action were nearly all preparatory for further legal moves. So for example it called for ‘creation of a standing review body on picketing to provide a firm basis of fact for any new legislation that may be needed’ and ‘the preparation of legislation to be introduced if and when necessary’ to provide for injunctions against picketing.

No one should get the impression that the EEF is a soft touch however. In the same document they called for legislation which would allow firms to sack strike leaders without compensation and to suspend workers without pay in the event of a dispute.

So towards the end of the period under discussion the key employers’ body remains fairly cautious about (a) pushing the unions too far; and (b) who it wants to attack. The EEF is concerned with the militants, not the ‘problem of union power’ as such.

Elsewhere, however, there was a major change in the climate of opinion about the ‘balance of power in industry’. One reason for the demise of the idea of ‘employer solidarity’ which loomed large in CBI and EEF discussions in 1979 was the collapse of employer unity on a wide number of fronts under the impact of the recession. In the national print dispute, some firms were quite prepared to do deals with the NGA and grab work off others; the smaller firms would not back the hard line put by the big employers because of lack of resources to withstand a long strike or lock-out. The architect of the employer solidarity edifice, Sir Alex Jarratt of Reed International, was left with his print-works paralysed by the NGA and his NUJ employees at IPC refusing to return from their lock out until they were paid in full for the period of the dispute. Reed’s had to give in. In June 1980, shortly after both disputes ended, the CBI discovered that after some months of meetings, canvassing of support etc. only 10% of its members bothered to reply to a circular on the question of insurance against strikes. Of these replies only half were favourable to the idea. The CBI dropped it shortly after.

This was not really surprising. The developments in national bargaining over the past 12 months have shown how much a lot of employers want to go their own way on pay and conditions etc. This was the position adopted by GEC and some other companies during the 1979 engineering dispute. It surfaced again during the recent building industry negotiations, when Costain resigned from one employers’ body in order to do its own deal with the T&G. There have been some similar moves in the chemical industry, and in shipping (with a traditionally right-wing Tory employers’ group) a series of companies, chiefly prosperous multinationals, settled separately with the NUS during the seamen’s dispute.

The lack of unity on the employers’ side has not however blunted the shop-floor offensive in individual firms. Companies have simply felt strong enough on their own. They have been imposing their own conditions on pay increases: flexibility, mobility, the end of demarcation, de-manning, an end to one-in/all-in on overtime, tightening up on breaks, higher production targets, production workers doing their own maintenance etc. All these elements have frequently been introduced or revived as part of basic pay deals (often very low anyway) rather than as trade-offs for more money. The productivity gains have been very considerable, and very cheaply won. The only front on which management has not succeeded is hours. On the whole, employers are having to concede shorter hours and they are not getting workers to pay for it by cutting breaks or agreeing worse conditions. With this exception, however, there has been a generalised offensive on efficiency.

In this move, firms have been helped by short-time working. We described earlier how short-time working, aided by government subsidies, had led to the temporary breakdown of stewards organisation at Talbot Stoke. Another by-product was that management succeeded in winning far more than 60% output from a three-day week. Firms have used short-time as an opportunity of tightening up on lateness, sickness, holidays; as a lever to persuade workers to do different jobs; as a way of exerting much greater employer control over the work process than would be the case on normal five-day working.

Part of the problem with the short-time working subsidy is that it has generally been welcomed by trade unionists as an alternative to redundancy – but it has given management the whip-hand to decide what to do, who to call in, when and where. A further difficulty was that the subsidy was originally quite attractive – 75% of pay for six months, which firms often made up to 80 or 90%. Subsequently the level of compensation has dropped: workers have to get by on half normal pay for up to nine months: they may be working more intensively for less money.

Looking at the official picture of strikes in the 18 months to June 1981 is – for once – quite a good way of getting the measure of the class struggle in general: so long as you do it in a selective way. Appendix 1 gives some details of strikes in this period, taken from the DE Gazette which point to a number of facts. Very large strikes distort the picture in 1980/81. If you exclude the steel strike, a number of features emerge. For the first time on record strikes about pay were in a minority. Even according to these crude figures, defensive action predominates. Taken with the figures for AUEW official disputes, the evidence is overwhelming. In a period which has witnessed the fastest increase in unemployment ever, it is hardly surprising that in the first six months of 1981 the number of strikes about redundancy trebled over the previous six months and was double the number in the equivalent period of 1980.

The last two years have seen workers increasingly on the defensive. But they have not seen organisation wiped out. Even in the worst cases of defeat, like Longbridge, the spark of militancy has been kept alive, new people have come forward, and the possibility of victories has been there. The role of union leadership in compromising and retreating and occasionally simply betraying strikes has been as important as ever. While union general secretaries have been shut out of the corridors of power, the lower ranks of the bureaucracy have shown their teeth, particularly in the T&G. On occasions the political splits within the bureaucracy have been important. One such occasion was the Isle of Grain dispute, where the line-up of antagonists more or less mirrored the fights on TUC general council committees. As the next general election beckons and the infighting in the Labour Party becomes nastier, we can expect still more of this. The danger of getting seduced by the spectacular political show is enormous. Discussing the T&G in this article we have shown how crucial is the weakness of the rank and file network and how irrelevant the politics of the ‘left’ and ‘right’ within the bureaucracy have been to the needs of the real struggle at the point of production.

The lesson that emerges from a study of the unions over the period of the Thatcher government is that the worse the situation becomes the more abstracted are the subjects of debate. The ‘Piss and Wind Union’ was how Paul Foot described the most recent TUC assembly in Blackpool. This would be a polite description of the debates about incomes policy and free collective bargaining, considering that under present day free collective bargaining we have a collection of union full-timers who in the main conceive their role as the avoidance of any struggle that might rock the boat. The union bureaucracy has been and is very important to Tories and employers alike. One reason why the victimisation of Derek Robinson was not the green light for a general attack on stewards is that the mediating role of the union leaders would have been upset by such an offensive. In the public sector union leaders have been essential to the success of the 6% cash limit. In the move towards central bargaining in the mechanical construction engineering industry (large sites) of which the smashing of the Grain laggers was an integral part, the role of the officials was crucial. At BL, the TGWU made the introduction of the slaves charter a formality. On the railways the leaders of the NUR and ASLEF lined up the most formidable array of industrial solidarity gathered since the 1920s – and settled for ‘understandings’ on productivity that could see the loss of thousands of jobs, and so on.

On the other hand the struggles that have taken place have been far more political – in the real sense – than the battles in the ‘good old days’ of the early 1970s. Anti-Toryism was then enough to animate the struggle. Stewards could get by on the basis of their own organisation. Those who are prepared to resist the employers, the government, the courts, the police, their own officials in 1981 and 1982 are far more in need of the ideas of revolutionary politics if they are to recreate the rank and file organisation and militancy needed to win. Fragmented struggles in isolation are now doomed to almost certain failure, at enormous cost. The lesson ‘If you can’t spread it, you might as well forget it’ was never clearer, and the network of support for collections, pickets, resolutions of solidarity was never more necessary.

A feature of the last period is the way in which large scale set-pieces have generally gained something or, at worst, been bad draws, compared to the almost universal defeat of isolated strikes. This should not be a recipe for doing nothing until the big strike comes along. The task is to link disputes, as ever: they almost certainly can be linked by revolutionaries, and, increasingly, it is only revolutionaries who will link them. Thus the need to get involved in every dispute or potential dispute, whether from the inside or the outside, is fundamental. The role of political minorities has, in fact, been to turn disputes, or at least to make it possible to win. The presence of revolutionaries on the inside at Ansells before the strike started could have resulted in successful picketing of other breweries in the first week of the strike rather than the last desperate throw it turned out to be.

The Government is now committed to the riskiest part of its entire strategy. Despite all the noise about the failure of monetarism, the Tories and the recession have altered the general balance of power in the class struggle in a way inconceivable 5 or 6 year ago. The atrophy of much shop-floor organisation preceded the Thatcher government by several years – it was spawned by some of those now planning the next social contract. But despite this process much of the tradition of 1970s is still around, if dormant.

It is remarkable for example how many factory occupations there have been – a dozen or more over the last six months. The mass picket still persists, the tactics of an active strike have been reaffirmed many times over the past two years.

There are thus two contrasting ways forward. The way of action and self-reliance and learning in the struggle or the search for bureaucratic solutions, the hope that someone else or something else will do it for you. The fear in the minds of the ruling class is that having taken the offensive they will reap the whirlwind. Already there are those who counsel caution, because they fear a shop-floor backlash when times improve, and there are those like CBI President, Sir Raymond Pennock, who fear that ‘The militancy of the post-war period was bred among the young men of the 1930s.’ The way we can ensure that Pennock’s nightmare becomes reality (for women and men alike) is to seek out and nurture the struggle that exists and lives.

All the political arguments which have tied workers to the status quo have to be won quite decisively amongst new layers of workers before this climate is likely to change. A rank and file movement will certainly have to be built, but it cannot be built except through building and extending the influence of socialist ideas in the workplaces. Those who do wait for the next Labour government to bring the promised land could wait an awfully long time.

|

Table One: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Working days lost |

||||

|

|

Number of |

Workers |

All |

% from large |

Excluding large |

|

1980 |

1,330 |

830,000 |

11,965,000 |

74 |

3,110,900 |

|

1979 |

2,080 |

4,584,000 |

29,051,000 |

77 |

6,681,730 |

|

1978 |

2,471 |

1,001,000 |

9,391,000 |

41 |

5,540,690 |

|

1977 |

2,703 |

1,155,000 |

10,378,000 |

31 |

7,160,820 |

|

1976 |

2,016 |

666,000 |

3,509,000 |

– |

3,509,000 |

|

1975 |

2,282 |

789,000 |

5,914,000 |

14 |

5,086,000 |

|

1970 |

3,906 |

1,793,000 |

10,908 000 |

33 |

7,308,000 |

|

1965 |

2,354 |

868,000 |

2,932,000 |

18 |

2,404,240 |

|

1960 |

2,832 |

814,000 |

3,049,000 |

8 |

2,805,080 |

|

* A large strike is defined as one resulting in 200,000 working days or more being lost. |

|||||

|

Table Two: |

|||

|

|

January– |

July– |

January– |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of stoppages |

797 |

465 |

666 |

|

Working days lost |

11,100,000 |

810,000 |

2,561,000 |

|

Workers involved |

613,300 |

176,100 |

1,048,000 |

|

Working days lost per |

18.1 |

4.6 |

2.4 |

|

* All figures were subject to revision at a later date. |

|||

|

Table Three: |

||||||

|

|

January– |

July– |

January– |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Number |

% total |

Number |

% total |

Number |

% total |

|

Pay and related |

406 |

50.9 |

201 |

43.2 |

327 |

49.1 |

|

Hours |

13 |

1.6 |

17 |

3.7 |

16 |

2.4 |

|

Redundancy |

43 |

5.4 |

33 |

7.1 |

92 |

13.8 |

|

Trade union matters |

51 |

6.4 |

18 |

3.9 |

36 |

5.4 |

|

Working conditions |

65 |

8.2 |

39 |

8.4 |

48 |

7.2 |

|

Manning |

126 |

15.8 |

94 |

20.2 |

83 |

12.5 |

|

Dismissal/disciplinary |

93 |

11.7 |

63 |

13.6 |

64 |

9.6 |

|

* All figures subject to revision. |

||||||

|

Table Four: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

January– |

July– |

January– |

|

Total |

10,587,900 |

605,600 |

1,349,300 |

|

Total excluding steel strike |

1,787,900 |

– |

– |

|

Non-pay related |

533,700 |

381,200 |

745,300 |

|

% of total |

5 |

62 |

55 |

|

% of total excluding steel strike |

28 |

– |

– |

|

Redundancy |

108,200 |

123,100 |

213,800 |

|

% of total |

1 |

20 |

16 |

|

% of total excluding steel strike |

6 |

– |

– |

|

Sources: DE Gazettes. |

|||

|

|

ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 14.9.2013