ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

First published in International Socialism Journal 2 : 20, Summer 1983, pp. 55–81.

Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg.

Marked up for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

|

Before the British conquests the states of South Asia [1] were ruled, in the main, by militarised bureaucracies. These classes formed autocratic regimes which smothered the merchant classes who were, unlike their counterparts in feudal Europe, prevented from developing into capitalists.

The autocratic societies decayed as the exploited classes were unable to replace their ruling classes, and so all fell victim to British capitalism in the period of its expansion. The British systematically destroyed all the old ruling class in the territories that they conquered. They did the same to many but not all of the merchant classes who might have developed into capitalists. Only in west India, where British power had been most retarded and a significant group of merchants had collaborated with the East India Company for a hundred and fifty years, did an indigenous capitalist class survive the establishment of British rule.

Using their direct political power, British capital discriminated against any effort of Indian capital to grow. Indian capital was excluded from participation in the construction of the railways, and it was not until the 1890s that the government of India was permitted to purchase iron and steel goods produced in India. Before 1914 practically the only significant branch of production occupied by Indian capital was textiles. Minor units only existed in coal, iron and steel, and in engineering.

Within thirty years, however, British imperialism was struck by three major crises of international capitalism. Each of these ruptured the ties which bound India to British capital. Despite attempts by the British to re-establish themselves, Indian capital emerged from each crisis stronger in relation to British capital. World War One gave them their first chance, for with the Mediterranean closed by German submarines and home industry working to maximum capacity the British perforce had to turn to Indian capitalists to supply the armies in the East. The war boom gave Indian capital a boost which could not be reversed. This was repeated by the blows which British capital received from the Depression and World War Two. [2]

When the exhausted British cut and run from their Indian Empire in 1947, the ruling class which replaced them consisted of two major but very different elements. The first was industrial capital which had established itself over the previous fifty years. This section was a national class in that it conceived itself as the core of the Indian state. The other section was the conglomeration of rich farmer and associated petit-bourgeois groups. They had fought the British in order to get land reform, and access to the market and to credit. They were regionally based, and each threw up at least one distinct local leadership which intervened at the national level on behalf of the regional section. Both these major sections were represented by the organisation which had dominated the campaign for independence, the Congress Party. [3]

The problem for the regime has always been not only to balance the interests of the two distinct major sections, but also the competing claims of each regional section of the rich farmers and petit-bourgeoisie. As the bulk of the cadre of the Congress Party has always come from the regional rather than the national section of the ruling class this has always been an immediate political problem for the ruling party.

In the Fifties and early Sixties, however, the problem remained latent. The Indian economy was carried along on the coat tails of the great boom. To put it crudely, enough resources were available to satisfy each component of the ruling class. The state provided increasing assistance to the production of rich farmers, and simultaneously increased the number of government jobs and judiciously spread industrial projects around the country so that the employment objectives of the petit-bourgeoisie were at least partially achieved. Industrial capital received its particular national boost from the rapid development of state capital. This spanned iron, coal, steel, railways, heavy engineering, machine tools and the aircraft industry. This strategy had been advocated by a group of leading Indian capitalists in the Bombay Plan of 1944. They saw it as a way of leaping over the backwardness of domestic capitalism. It also, of course, enabled them to reap the benefits of investment without having to pay for it. [4]

Although constrained by the overall backwardness of Indian capitalism, the development of state capital had several outstanding effects on Indian society. Not only did it massively extend industry, but it also produced a major expansion of the working class often into regions with practically no pre-existent working class. [5] It also added a third section to the Indian ruling class. The managers and planners of state capital, and their auxiliaries in such occupations as education, journalism, the law, the police and the military, rapidly formed themselves into a distinct section of the ruling class with clearly defined interests and objectives. The formation of this section was central to the politics of the ruling class when the boom ended.

The end of uninterrupted boom came early to India, in 1965. It undermined the stability of the ruling class, because not only did it trigger massive struggles by workers and peasants against attempts to solve the crisis at their expense, but it also triggered a process of fragmentation of the regional sections of the ruling class. Deprived of their desired economic gains by the crisis, factions began to defect from the Congress in many states. This process became a major trend after the 1967 elections, and had become chronic by 1969-70. In some areas, especially West Bengal, ruling class power was threatened by the upsurge of the working class combined with its own factionalism. [6]

It has been the historic role of Indira Gandhi to rescue the Indian ruling class from the predicament in which it has placed itself. It is a role that she has been performing with great energy, skill and ruthlessness (although with declining success) for eighteen years. Her domination of bourgeois politics flows from the fact that no-one else could possibly have carried on the act for the length of time that she has done. The base of her faction in the Congress (known as the Congress (I)) is the state capitalist section of the ruling class. It viewed with horror the chaos of the late Sixties, seeing its objectives of the national expansion of industry and the international expansion of the power of the Indian state put at risk by the regional section of rich farmers and petit-bourgeois squabbling over the allocation of a few thousand local government jobs. These pork-barrel politics, which in a ludicrous mixture of farce and tragedy risked the stability of the state, united the state capitalist bourgeoisie with their colleagues in private capital in a mixture of fear, horror and disgust in equal measure.

Indira Gandhi defeated the workers’ revolts in the early Seventies by a mixture of vicious repression, cynical populism and a successful war with Pakistan in 1971. This temporarily brought the dissident bourgeoisie into line. By 1975, despite a comprehensive defeat of the railway workers in the previous year, the regime was again seriously threatened by divisions in the ruling class as India was hit by the world economic crisis. An aged Gandhian leader, J.P. Narayan, put himself at the head of a mass movement of dissident regional farmers and petit-bourgeois which undermined the state governments of Gujerat and Bihar. By threatening to extend these movements to a national level he put at risk not only the regime, but also the ruling class as a whole.

The Emergency of 1975–77 was Indira Gandhi’s response to this threat. It was not primarily aimed at the working class, although workers and peasants suffered greatly under it. Indira Gandhi needed no additional weapons against them than she already possessed, although the Emergency was used as the occasion for new sweeps through left-wing and working class activists, and by employers to batten down on their workers. The Emergency was essentially an attempt to centralise the ruling class by crushing the power of the regional sections, the rich farmers and petit-bourgeois (as well as the few local capitalists), which was expressed in the power of local Congress party bosses. This was the purpose of the promotion of her infamous son Sanjay, a thug of the first order, who was nevertheless a talented political organiser. The Youth Congress, which he organised out of the children of his mother’s social base, was intended as an organisation existing in each state which was directly responsible to the centre and not to the local Congress leadership. In this way Indira Gandhi hoped to achieve long-term control of the regional sections of the ruling class and to crush the power of the local bosses.

The attempt failed, because her social base was not strong enough to carry it off; Sanjay’s gilded youth failed to provide the foundations of a new order. In 1977 the biggest boss of all, Jagjivan Ram, defected when he realised that he was about to be carved up by Sanjay in his home state of Bihar. Between January and March 1977 the regime literally fell apart as it became apparent that it did not have the capacity to carry out the task it had set itself. After the elections of March the disparate dissident factions of the regional ruling class, together with a motley collection of social democrats and the neo-fascist Jan Sangh found themselves in power as the Janata coalition. It is difficult to imagine if they or Indira Gandhi were the more surprised.

The Janata regime lurched along for two and a half years. It collapsed, as might have been expected from its constituent elements, amid a truly spectacular display of factionalism, splits and defections. This lunatic shambles provided Indira Gandhi with the opportunity for her return to power in 1980. However, the collapse of the Emergency had brought about irreversible changes. These did not only affect the ruling class, for the working class had also changed as a result of the Emergency and its collapse. It is to this that we now turn.

As is the way, the Indian working class grew along with capitalism. This meant that it was formed in a particularly uneven manner, and reflected the backward nature of Indian capitalism.

The first significant section of the working class, the textile workers of west India, were typically recruited from their home villages by local labour contractors or ‘jobbers’. These people accompanied the new workers to the mills and organised them into their sections, acting as a kind of foreman in the mill as well as a broker who arranged their accommodation and otherwise looked after them in the city. They acted as a block to the development of independent working-class organisations. On the contrary, they directly harnessed the working class to the nationalist movement, as these petit-bourgeois jobbers were usually enthusiastic supporters of the Congress. The great general strike of 1908, in protest at the imprisonment of the Congress leader B.G. Tilak, took place despite the total absence of trade unions. It was organised by the jobbers. After World War One these same people provided Mahatma Gandhi with a base inside the west Indian working class.

Workers’ struggles flowed in the wake of the boom of World War One. Strikes began breaking out in different parts of India from 1917. What usually happened was that the petit-bourgeois nationalist politicians seized the leadership of these strikes, offering negotiating and legal skills which the workers lacked and for which they felt a need. In addition, as there was no socialist tradition of any kind in India prior to the Russian Revolution, the workers, coming from peasant experience where political leadership was habitually provided by petit-bourgeois nationalists, accepted the leadership of such people without serious demur. So when the All-India Trade Union Congress was formed in 1920, all the main union ‘leaders’ were in fact nationalist politicians. [7]

This set the pattern for trade unionism in India. As it exists today, unions are organised into five principal federations, each of which is affiliated to a political party, (or in one case, a set of parties). Habitually, the official leadership is held by a party functionary, of greater or lesser rank depending on the importance of the union. At the time of the national rail strike in 1974, the leaders of the two national rail-workers federations were S A Dange, General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (CPI) and George Fernandes, a national leader of the Socialist Party, a minor social-democratic splinter from the Congress.

The major federations are: the All-India Trades Union Congress (AITUC) – affiliated to the CPI; the Indian National Trades Union Congress (INTUC) – a Congress split from AITUC in the 1940s; the Centre of Indian Trades Unions (CITU) – affiliated to the Communist Party (Marxist). (It was a 1970 split from AITUC.)

Less importantly, there is the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) the creation of the neo-fascist Jan Sangh, mainly deriving its support from petit-bourgeois salaried employees; and the Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS), the union organisation of the Socialist Party. It suffered when the party entered the Janata coalition in 1977 and vanished as a distinct entity. The union has not recovered from the experience.

Finally there are also federations aligned to regional left parties which have only local significance.

In 1982, the official estimates for the total membership of the three largest federations were 2,400,000 for INTUC, 1,700,000 for CITU, and 1,400,000 for AITUC. [8] This out of a total population of almost 700 million and an urban population of at least 160 million. [9] Most of these workers are organised in unions specific to particular factories or companies, the federations being, in fact, precisely that. They are collections of unions, affiliated to a political centre, usually with minimal contact with each other. The federations are also, and crucially, the property of the party, to be used as the party decides.

It is not really surprising that INTUC, the union of the regime and therefore of collaboration with the ruling class, should treat its members like that. The behaviour of the left, and especially the CPI and the CP(M), however, follows from their political origin. As there was no socialist tradition of any kind in India prior to 1917, the first attempts to form a communist party were necessarily made by small groups of disillusioned young nationalists, who had the most skeletal notions of Marxism, which were not helped by the extremely intermittent nature of the contact that they were able to make with the Communist International. [10] By the time that any viable organisation could be established, in the mid-Twenties, the International had fallen under the sway of Stalin. Lacking any contact with Marxism or the international workers’ movement independent of the International the small core of the CPI adopted everything they received from Moscow as gospel. Although they consequently suffered considerable isolation during the Third Period’ of sectarian attacks on social-democrats instituted by Stalin in the period 1928–33, the adoption of the policy of the Popular Front by the International in 1935 was the start of a period of growth for the CPI.

The class alliance set out in the Popular Front enabled the CPI to work with a significant section of Congress activists, who in the main came from rich farmer and petit-bourgeois families. They focussed on a left faction of the Congress, the Congress Socialist Party, which mainly consisted of activists dissatisfied with Gandhi’s leadership. The superior organisational skills of the CPI, and the attraction of their class unity politics for young petit-bourgeois militants, enabled them to pull a number of people out with them when they were expelled from the Congress Socialist Party in 1939, after the leadership of that organisation had capitulated to Gandhi. [11]

The CPI grew considerably during World War Two, despite some losses over their policy to support the war and oppose the anti-British struggle after 1941. [12] Their new-found legal status enabled them to organise freely, although this rebounded on them somewhat after 1945 when they were open to the charge of collaboration with the British. The principal problem at that time was rather the reverse – having discounted a workers’ revolution, they not only finished up tailing the Congress, but also the Muslim League, the Islamic communalist organisation, as well. Never having possessed a perspective of the centrality of the working class, they were compelled to adapt to the nature of the bourgeoisie with whom they wished to unite, in all its regional and communal aspects. On the other hand, since they adopted wholesale the revisionist concept that there was a unitary bourgeois interest (which was betrayed by anti-patriotic bourgeois traitors), then as later they ended up in the ludicrous position of trying to support both the bourgeois factions, in this case the Congress and the Muslim League. This nonsense meant that the CPI was incapable of doing anything to oppose the communal slaughter which swept north India in 1946-7. [13]

Under pressure from sections of their worker and peasant base, elements of the CPI overturned the pro-Congress leadership of P C Joshi, only to embark on an equally absurd ultra-left offensive which collapsed in a considerable mess in 1949–50. [14] Following this, and a swift Russian re-evaluation of prime minister Nehru following his support for Russia in the Korean War which began in 1950, a stable right-wing leadership was imposed on the party with a perspective of critical co-operation with Congress and the ruling class. This was centered on what became known as the New Democratic Revolution. This concept, which will be familiar to many readers and which was basically copied from the Chinese party, states that the principal conflict is with imperialism, and the aim, therefore, is to set up a national democratic state, using a four-class alliance – the working class, the peasantry, the ‘toiling middle classes’ (i.e. the petit-bourgeoisie), and the progressive national bourgeoisie (ie any local capitalist who wasn’t in cahoots with the foreigners). In practice this meant tailoring their politics to those of their hoped-for ruling class supporters. Indeed the progressive national bourgeoisie has proved to be a particularly difficult fish to net, most of the candidates on offer having declined every offer that has been made, however humble. [15]

The result of the adoption of this perspective was a consistent move to the right by the CPI as it trailed after the ruling class in its hopeless pursuit of the progressive national bourgeoisie. The party energetically supported the efforts by regional sections of the ruling class to re-organise the constituent states of India on a linguistic basis. This had been a long-standing demand of the Congress before independence as linguistic states conformed, more or less, to the structure of the regional ruling class. Since the different sections did not always agree on what should be done in particular areas, some of the campaigns involved demonstrations and minor riots. The CPI hoped to gain electoral advantage from involving itself in these campaigns. However, even in Andhra Pradesh state, where the party had built a mass base in both the Telengana region and in coastal Andhra in militant peasant campaigns in the 1940s, their hopes were dashed in elections held in 1955 and 1957. Given the choice between the CPI playing petit-bourgeois politics and the genuine article, voters chose the latter.

The party became increasingly committed to the parliamentary road to socialism. They saw themselves in alliance with a progressive regime, and were even more convinced of this perspective when the state sector of industry was expanded with a large Russian component from the mid-Fifties. At its Amritsar Congress in 1958, the CPI made a definitive statement of its politics. It committed itself to a peaceful (i.e. parliamentary) transition to socialism and changed itself from a cadre (i.e. activist) party to a mass (i.e. electoral) party as a necessary consequence of this decision. [16] Ironically the membership, from a 1958 peak of 229,000 fell to 135,000 by the next congress in 1961. [17]

There were constraints on this shift to the right. The CPI existed on the assumption that it was the only party which was the authentic voice of the working class and peasantry. It had to respond to the real problems of these people, for in spite of all the party’s attempts to marshall them behind sections of the ruling class they persisted in engaging in struggle against their intended allies. The history of the CPI has been marked by this continual attempt to reconcile the irreconcilable. [18]

One section of the party, the left of the 1940s, had never been reconciled to supporting the Congress regime. Accepting the politics of the new democratic revolution and the four-class alliance, they eventually solved their problem by declaring that the Congress did not represent the progressive national bourgeoisie. The question came to a head with the war against China in 1962. The right leadership, true to their politics, rushed headlong into patriotic support for the regime. The left, to its credit, held out against this disgusting display of national chauvinism, and were locked up for their pains. That delayed the split until 1964, when amid a spectacular display of denunciations and mutual expulsions, the left reformed itself as the Communist Party of India (Marxist) – or CP(M).

As has been said, the basic politics of the CP(M) are very similar to those of the CPI. They reject the workers’ revolution for India, in favour of the four-class alliance – the politics of the Popular Front. This has meant that the party has become utterly reformist and parliamentarian. In the late 1960s it adapted to the fact that its support was concentrated in two states, West Bengal and Kerala, by proclaiming that the highest expression of the class struggle was the conflict between the central government and the states. This meant that their first priority was the survival of the coalitions which it led in those two states. To achieve this they were obliged to perform all kinds of accommodations with dissident factions of the ruling class whose parliamentary support they required. These manoeuvres, which were universally contrary to the interests of the CP(M)’s working class and peasant base, were fruitless. Indira Gandhi had more to offer the dissident regionalists, and the CP(M)-led governments collapsed amid considerable slaughter, as the ruling class counter-attacked in 1970–72.

Nevertheless, the CP(M)’s consistent opposition to Congress meant that they gained a reputation as the most militant trade unionists, so that their unions became the natural home for the most active and militant workers. This reputation has sustained them through their many tribulations.

When the CP(M) returned to power in West Bengal in 1977 this perspective had been slightly amended. As they now had an absolute majority in the state assembly they posed themselves as the only efficient and non-corrupt party available to govern India. In this they were undoubtedly correct, and their government in West Bengal has carried out a significant land reform effort for the benefit of share-croppers, the major exploited agrarian class in West Bengal. It also meant that the state has become one of the most congenial for capitalists. The government’s desire to prove itself as an efficient administrator for capitalism has led it to employ its strength in the working class through CITU to smother workers’ struggles. Where this political influence has not been sufficient, such as the Santaldih power station strike, where the workers were organised by a Maoist dominated union, the CP(M) have been quite prepared to use repression. [19]

It was this willingness of the CP(M) to use repression in support of its reformist politics that produced the Maoist split from the party. The term ‘Naxalites’, which came into common currency to describe this movement, originated from the Naxalbari district in West Bengal, where in 1967 Chinese-influenced CP(M) members were organising a land seizure movement among poor peasants. Eventually they were denounced by the CP(M) leadership, who insisted on total parliamentary legality. The movement was suppressed by police acting on the orders of CP(M) leader, Jyoti Basu, who was also police minister in the state government. Within the next year this had triggered splits from the CP(M) all over India. This was a time of increasing economic and political crisis, and a time when the ruling class appeared to be in real danger. It was not difficult for the Maoist groups to organise around them considerable numbers of petit-bourgeois youth, who had genuine revolutionary commitment and moved towards the only political perspective available which appeared to offer a way of transforming Indian society.

But yet again the basis of the politics had not changed. The Maoists (or Marxist-Leninists, as they termed themselves) still adhered to the politics of the democratic revolution and the four-class alliance. They responded to the degeneration of the CP(M) by saying that it was not possible to achieve this through parliament. It had to be achieved by prolonged armed struggle. It was, and is, reformism with machine guns, an attempt to shoot their way to social democracy. This does not deny the commitment of thousands of young revolutionaries, nor the ability of some who have more recently succeeded in organising agricultural labourers and poor peasants at a local level in Bihar and Andra Pradesh. But when the politics go beyond the local level, then they are caught up by the hopeless reformism of the chase for the progressive national bourgeoisie, a process which led at least one Maoist faction to support the Janata in 1977.

The result at the end of the sixties was a disaster. Adopting a stupendously mechanical version of the Chinese experience, and combining that with an apocalyptic vision of the imminent collapse of the Indian state, the Maoist groups in north India (there never was a real unified organisation called the Communist Party of India (Marxist Leninist)), went on an ultra-left binge of physically eliminating landlords. Believing that the countryside was the seat of the revolution and that the ‘Red Army’ was its agency, they instructed their members to abandon both the towns and mass organisations in favour of guerrilla actions which rapidly degenerated into a campaign of individual terrorism. After initial shocks, the regime was extremely successful in eliminating the threat. The clandestine nature of the Maoist groups made it extremely easy for the police to penetrate them (since no-one knew anyone else, there was little chance of identifying a police spy) and the lack of a mass base in the villages made the peasants and workers at best passive and at worst hostile towards people who turned up out of nowhere suggesting that they bump off the local landlord. The Naxalite campaign ended with mass arrests and a large number of activists being shot while attempting to escape. [20]

Coming on top of the degeneration of the CPI and CP(M), this failure of a revolutionary movement produced both disillusion and a reaction against parties as such. The typical behaviour of orthodox communist organisations in India has been to form themselves, write a programme, and call on the working class to support them. This was bad enough when carried on by mass parties like the CPI and CP(M), but ridiculous when performed by miniscule groups. By 1974 the prospects on the left were bleak indeed.

The Emergency, or rather its collapse, triggered major changes in workers’ organisations. The traditional organisations distinguished themselves by their uselessness. The CPI began by supporting the Emergency, and were only driven into opposition by the inconvenient arrest of many of their members and supporters under the Emergency measures. The CP(M) had no answer to the crisis and effectively stuck its head in the sand and hoped that it would go away. Fortunately for them, the regime collapsed from the inside after eighteen months. When the old parties emerged from their hibernation they found that many workers were no longer willing to unconditionally accept their leadership.

The collapse of the Emergency triggered a wave of workers’ struggles. A major centre was the newly industrialising area around Delhi, especially the towns of Faridabad and Ghaziabad. Here union organisation had begun prior to January 1977, and over 1977 and 1978 a string of vicious struggles followed as employers resisted unionisation. These new unions affiliated to the CITU, not because that federation had been very active in the struggles, or because the workers were attracted to the politics of the CP(M), but because they felt that they should join a federation and the CITU had the reputation of being the most militant. [21]

In a number of other places workers’ organisations were created which represented a conscious break from the old federations. Readers of Socialist Worker and Socialist Review will be familiar with at least two of these. At the Swadeshi Cotton Mills in Kanpur in 1977 workers literally chased out the CPI union organiser who had failed them when 200 occupying workers were killed by the police. They formed a genuine rank and file organisation, which united not only workers from all unions inside the factory but workers from other factories in the city as well. This organisation was able to call a city-wide strike of over 40,000 workers in support of its main demand, conceded in 1979, that the government nationalise the mill in order to prevent its closure by the owners. Although the movement has ebbed somewhat since then (as is the way with rank and file movements), it remains in many ways a model for the working class. [22]

In 1977 the corrupt CPI union at the Dalli Rajhara iron ore mines in Madhya Pradesh state was rejected by the workers as they formed an independent union in their struggle against a particularly vicious state employer. This is described in more detail in Part Three. Another independent union already existed in a similar coal-mining area, Dhanbad in south Bihar. The Bihar Collier Kamgar (Workers’) Union was formed in 1968 by a group led by A.K. Roy, a leading member of the CP(M) who left because of the party’s reformism. The union has been established on the basic issue of union democracy. (In the Bihar coal-fields, the management had promoted mafia unionism, using labour contractors as ‘union leaders’ to terrorise workers lifted out of tribal society into the most modern integrated coal and steel plants.) This movement is less controlled by the rank and file workers than was the Kanpur movement, as much revolves around Roy and his group. This is not because Roy is maliciously manipulating them for his own ends – all accounts are unanimous that he is a remarkably honest and dedicated man – rather that the colliery workers constitute a newly formed section of the working class, only very recently recruited from agrarian situations, and therefore with a very ill-developed working class consciousness. In Kanpur and Bombay, on the other hand, there are sections of workers with decades of trade union and political experience, and the ability to come to terms with comprehensive political perspectives of their own. In Bihar it is more a struggle simply to survive. [23]

In Bombay the failure of the established unions to support workers’ struggles enabled a freelance union organiser, Datta Samant, to undermine their position in the engineering industry. Samant used crude but effective methods to achieve substantial wage increases and so obtained a considerable reputation and support. This projected him into the crucial area of class struggle in Bombay, the textile industry. Following yet another shambles engineered by the official unions over a pay claim at the end of 1981, there were mass defections by textile workers to Samant’s union, which initiated the strike of 250,000 textile workers in January 1982, which, at the time of writing this article (April 1983) was still persisting. [24]

These organisations illustrate a definite trend in the working class. Many sections of workers are not willing to remain the passive members of unions controlled by the political federations, when that means that their interests and their struggles are subordinated to the tactical manoeuvres of the parties. For the first time in many years the Stalinist internal regimes of the AITUC and especially the CITU are no longer a barrier to contact with the organised working class, and revolutionary socialists now have access to a significant number of workers in struggle. These are the great gains of the years since 1977. That being said, there are a number of other conclusions which have to be drawn at this stage.

Firstly, the working class is still extremely heterogeneous. This shows initially in a regional form in that there are separate centres of workers in Maharashtra, Bengal, Delhi, etc. Most are literate in a regional language only. [25] Much more importantly, the class shows the features of uneven development. The workers have a most diverse range of consciousness, ranging from the primitive ideas of recent entrants such as those in Dalli-Rajahara and Dhanbad, through textile workers like those in Bombay and Kanpur, to engine drivers, who formed unofficial rank and file unions from 1968 onwards. The primitiveness or sophistication of the workers’ consciousness derives from the length and depth of their working class experience, and conversely on any surviving experience of another class. Now, while ideas and consciousness always change in the course of struggle, and sometimes very rapidly, without a party to generalise the various particular experiences of the working class the unevenness will remain. In this way the militancy of the miners will be unable to take them beyond the aims of democratic unionism, and the textile workers will be incapable of transcending the charismatic opportunism of Datta Samant.

Secondly, the workers’ organisations have not yet come to terms with the agrarian question. This is an immediate problem because many sections of workers have close links with families still on the land. This includes not only recent entrants to the working class in new industries, but also workers in long established industries like Bombay textiles.

This means that large numbers of workers are looking back over their shoulders towards the countryside. Often they are looking back to peasant families whom their wage supports. One result of this is, as in the Bombay textile strike, workers return to their native villages. While this assists the problem of personal maintenance, it undoubtedly dulls the cutting edge of the strike as it removes much of the element of collective action and makes organisation more difficult.

Much more serious is the existence of active peasant movements in the surrounding countryside, such as in Dhanbad and Dalli-Rajhara. These movements have demands which can, in theory at least, be met by capitalism – land reform, access to the market, and more credit. The intimate social ties between peasants and workers provide an easy route for reformism to penetrate to the heart of the workers’ organisations and for them to be pulled to the right by the peasant organisation. This clash is already present in Dhanbad. The situation can only be forestalled by insisting on the absolute centrality of the working class in its relationship with the peasants. The other side of the coin is that the workers’ organisations must win this leadership by demonstrating to the peasants that their aims can only be achieved through the victory of the working class.

The failure to achieve this was the cause of the collapse of the strike of 250,000 sugar factory workers in Maharashtra state in November 1979. The union leadership (from a collection of left parties) firstly adopted a strategy which would have ruined many small farmers (rather than the rich ones) and which would have propelled them into the arms of the factory owners. They also completely disregarded 150,000 migrant harvest labourers to the extent of not even telling them that a strike was to take place. When the folly of their plan became apparent, the union leadership compounded their idiocy by capitulating to the employers, when alternative perspectives were certainly available to them. [26]

This situation contrasts sharply with the one achieved, albeit briefly, in 1980–81 in Poland. Rural Solidarity, the organisation of Polish ‘peasants’ unconditionally accepted the leadership of the working class during this period. The panic this caused in the Polish ruling class was considerable, but without the workers’ victory it came to nothing. Without this relationship, rural producers are liable to be mobilised by reactionary parties (for which role there are several candidates in India), and used as a weapon against the workers, as happened during the revolutions in Hungary in 1919 and Portugal in 1975.

Thirdly, the workers’ organisations are still vulnerable to the attraction of regional bourgeois politics, usually dressed up in a tatty imitation of Marxist theory as the ‘national’ question. This reflects the reformism of the left parties, who still believe that there is a ‘national question’ to be solved in India. [27] It also connects with the ‘normal’, everyday experience of workers, most of whom live in a defined state which is more or less coterminous with the language they speak. This matters more because there is sufficient internal migration of workers to make it worthwhile for the right to use regional chauvinism to divide the working class. Since most of the left accept the premise that oppressed nationalities exist in India, they are incapable of confronting these chauvinist movements, as they concede half their case to start with. They are reduced to agreeing that there is a problem, but pleading that the victims should not be attacked. The worst example of this in recent years is Assam, where sections of the left have actually argued for support for the regionalist movement which has organised mass pogroms of Muslims since 1980. [28]

Fourthly, the CPI and CP(M) are incapable of being reformed. This is most explicitly revealed in their sectarian behaviour towards the new workers’ organisations. In the case of Kanpur they first tried to ignore the movement. When this proved to be impossible they tried to destroy it, and only when that tactic failed were they compelled to cooperate with it. In Bombay Samant’s union threatens to oust them from their long-established position as the dominant left organisations in the working class. Rather than transform their unions into more effective instruments of workers’ struggles, they have given verbal support to the strike while refraining from any effective action. Their hope is that the strike will fail, Samant’s union will collapse, and they will re-establish their position as leaders of the working class by default. For them the fact that this could only occur as the result of a historically massive defeat for the working class is purely incidental.

Fifthly, the future of workers’ struggles in India is restricted by the absence of any revolutionary socialist party. This is necessary not only for the workers’ revolution itself; even the building of unions across regions and industries can only be done, in existing conditions, with the aid of a party which can provide workers with a generalised perspective. The absence of such a perspective has kept the Bombay textile workers’ strike immobilised in a trial of endurance. Once the employers decided to sit it out, Samant has not been able to mobilise effective solidarity action. The only effective support seems to have come from the Lai Nishan Party, but it has support only in parts of Maharashtra state. The CPI and the CP(M) are of course quite happy to see both Samant and the workers sink, but this is a problem that any workers’ organisation will face. Samant’s politics prevent him from generalising the struggle. His political vision is bounded by collaboration with former associates in the Congress (I), even though he split from the party over the Emergency. In November this appeared to pay off when the government tried to get the employers to settle. When they refused Samant was left without any shots in his locker, because his conception of politics goes no further than playing the party game.

Without a generalised perspective workers remain trapped by the combined effects of regionalism imposed by the backward nature of Indian capitalism and the class collaborationist policies of the left reformist parties. In Britain, reformists were able to build a national trades union movement because the national capitalist class already dominated the regions. In India they cannot, without the intervention of revolutionary socialists.

The tragedy is that the experience of the left parties has produced a strong resistance to the formation of a revolutionary party amongst those people who should constitute its founding core. Either disillusioned with the idea of any kind of party or demoralised at the prospects of building one, the revolutionaries either limit themselves to their unions if they are workers, or engage in information-gathering and specialist assistance to unions if they are petit-bourgeois. All over India there exist small circles of socialists marking time in these activities, while Indian capitalism lurches towards another major crisis.

In many ways both the potentialities and the limitations of this situation have been expressed in a microcosm in the events surrounding the formation of a new union – the CMSS at Dalli-Rajahara. On the one hand there has been a massive, heroic and militant workers’ struggle, and on the other, the dominant ideas within that struggle – in particular those articulated by its charismatic leader, Shankar Guha Niyogi – have been confined to those of the democratic revolution, the construction of class alliances etc., which have been quite incapable of solving the problems of the exploited workers and peasants in Madhya Pradesh. This mixture of Maoism plus militant syndicalism is by no means confined to Niyogi in present day India, so it is worthwhile to look at this one case in further detail.

In June 1977 the two established unions at the Dalli-Rajahara iron ore mines in Madya Pradesh, one affiliated to AITUC, the other to INTUC, vanished almost literally overnight as their members deserted en masse. Both had established a role as agents of the management, the AITUC union naturally co-operating with the local representatives of the progressive national bourgeoisie.

The workers’ main bone of contention with the unions was that they had collaborated with the management in the maintenance of differentials between workers on the basis of their tribal or non-tribal origin. This meant that tribal workers were employed as casual, contract labourers, with a standard of living barely on the subsistence level. The non-tribal workers had permanent jobs and lived in company-built housing estates.

The collapse of the Emergency in January 1977 undermined the hold of the two unions, who had supported the regime. When the management failed to settle the bonus issue (bonus is of vital concern to Indian workers as the basic rate is usually below subsistence level) the workers struck. The workers approached a former Maoist militant who had set up an alternative union, Shankar Guha Niyogi. After a bitter strike and several confrontations

with the police, which resulted in eleven workers being killed, the management and the government retreated, made a settlement and recognised the new union, the Chattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh (CMSS – roughly translated as workers’ union). [29]

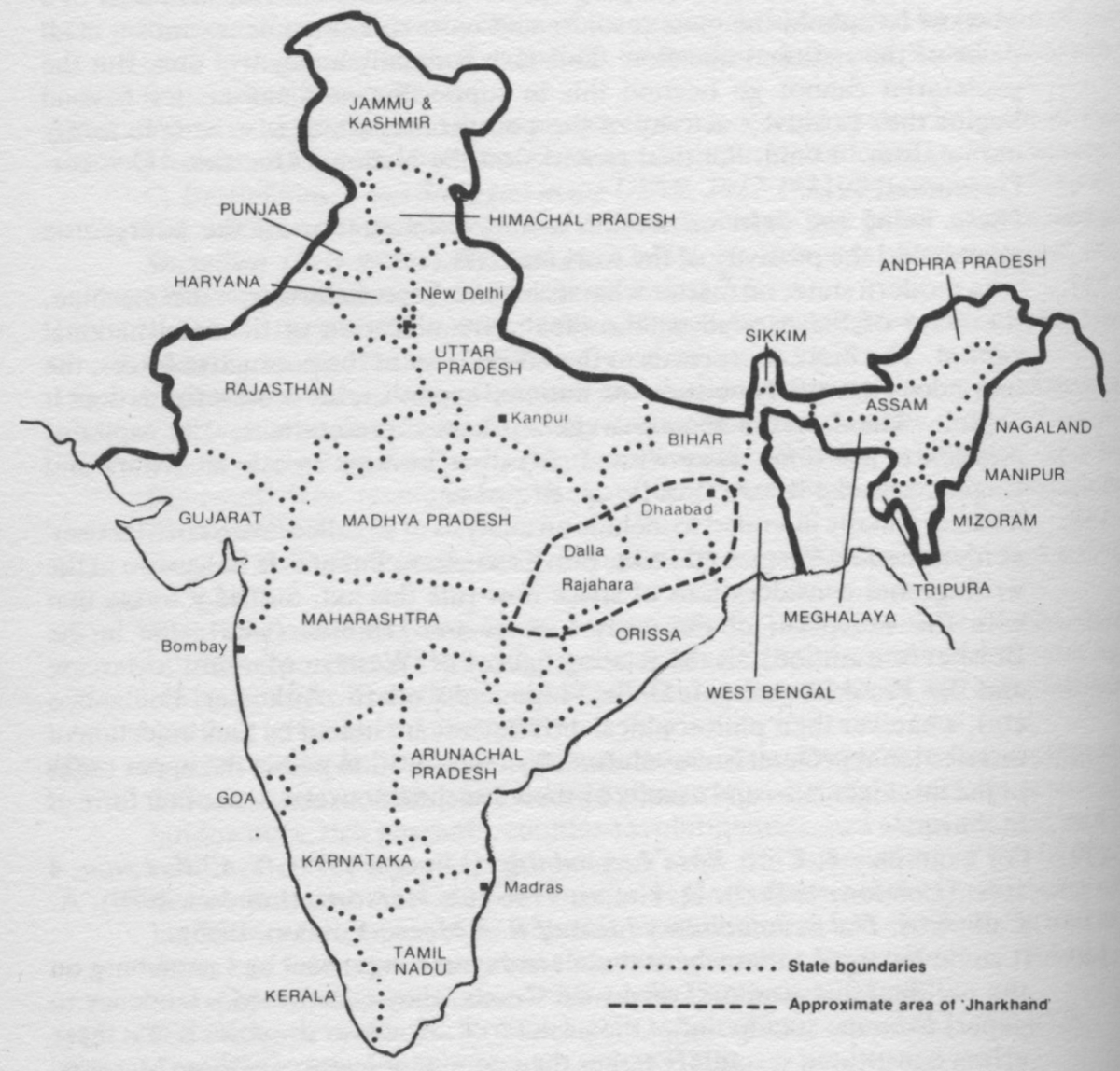

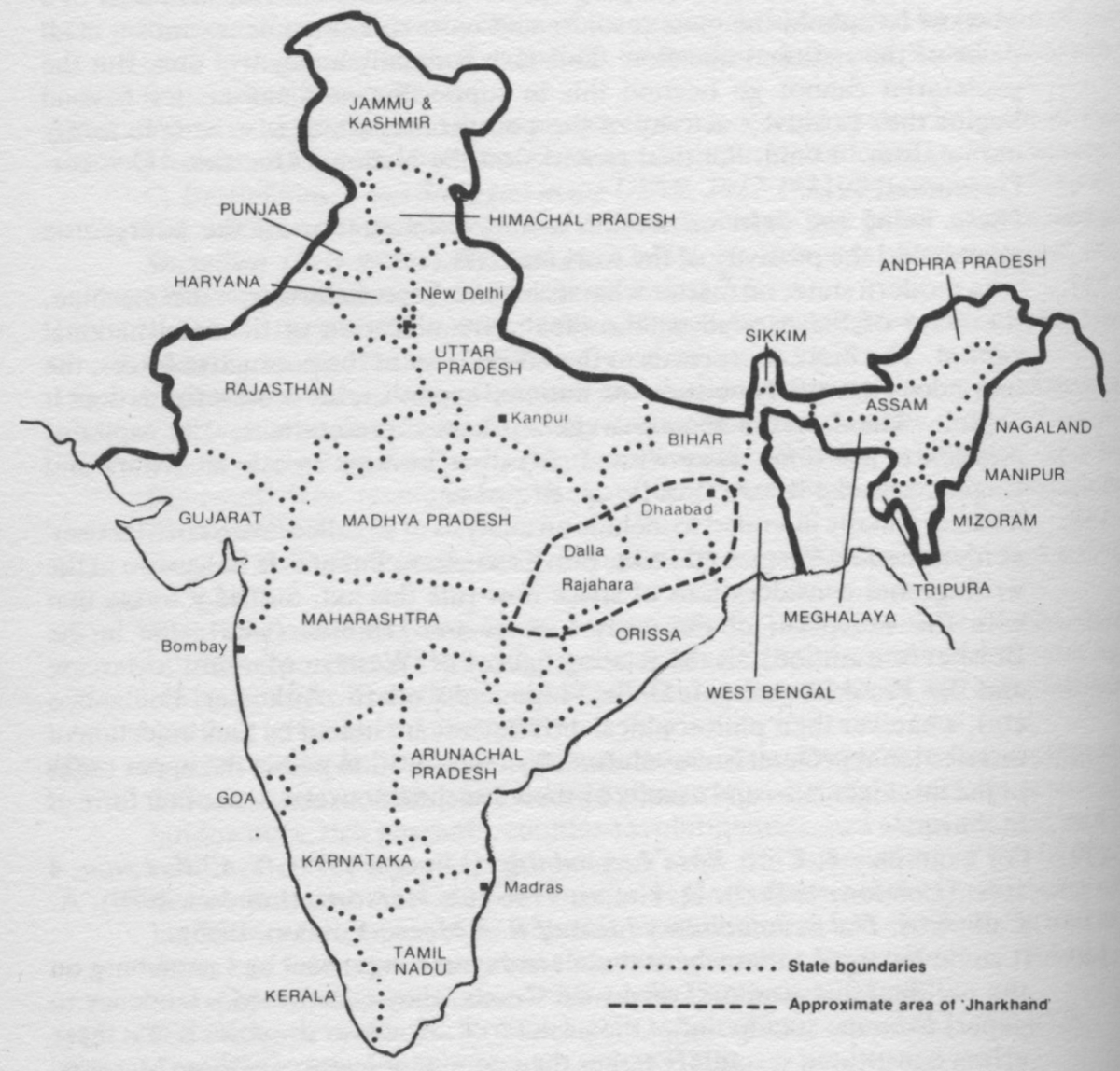

The situation in which the new union was formed was particularly complex. Dalli-Rajahara is in Chattisgarh, which is part of the ‘tribal belt’ of central-east India also known as Jharkhand. The greatest number of the approximately seventy million tribal people in India are concentrated here, although they are not necessarily a majority throughout the region. Until the establishment of British rule most of the numerous and distinct tribal peoples lived on the periphery of established class society, and negotiated arrangements with the neighbouring autocratic states. There was some intermittent cultural penetration – bits of Hinduism were incorporated into tribal religions, and the better-off tribal chiefs acquired some elements of the dominant Persian culture – but the tribes, mainly cultivating on communal land, were apart from the class society of the plains. [30]

After 1800 the British began a consistent policy of incorporating the tribal areas into class society. This in turn meant their incorporation into the world market, communal land being transformed into a commodity, and the domination of tribal economies by merchant capitalists, most of whom happened to be caste Hindus. When the tribals resisted, they were ruthlessly suppressed by the British. [31]

This incorporation into class society also entailed vicious racial oppression, both by British officials and by the merchants. After independence this continued, although legally forbidden, and many formal rights have been given to officially recognised tribal groups-the ‘Scheduled Tribes’. In most cases this took the form of positive discrimination for the tribal petit-bourgeoisie in education and state jobs as well as reserved seats in parliament and state legislatures. [32] This oppression took a new form when major iron ore, coal and steel works were established in tribal areas. The local representatives of the ruling class carved out a new role for themselves as labour contractors, disciplining the workers through gangsters in their employment and using the concentrations of workers to expand their profits from the liquor trade.

In Dalli-Rajahara a large part of the workers had been taken from being members of an impoverished peasantry, often in extremely backward conditions, and with very little access to the market as this was blocked by the merchants. They also had the experience of a hundred and fifty years vicious racist oppression. Once in the mines they were subject to company unionism backed up by gangsterism. In such conditions they had no previous experience of being part of the working class, let alone any political traditions. They did have many links with the people who remained in the countryside, and indeed still saw themselves as part of the same people, with the same interests. This explains the politics of the CMSS, and how Niyogi has been able to consolidate political leadership.

The achievements of the workers in the CMSS have been massive in the face of appalling conditions and an exceptionally vicious ruling class. They have beaten off several attempts by the state to crush the union by force. They have increased the level of wages, and have established equal pay for women. They have attacked the power of the liquor contractors, who promoted alcoholism amongst the workers. They have fought back against instances of tribal women being raped by the police – this is a typical piece of racist oppression of tribals. Since the state has failed to provide hospitals, schools or technical training, they have set them up themselves.

Yet despite all this, there are clear signs that the CMSS could be pulled behind one of the bourgeois parties. [33] The most likely candidate for this is some manifestation of the tribal bourgeois leadership who want a separate Jharkhand state, for all the regionalist aims that were set out in Part One. Niyogi, although he broke with the Maoists in the late 60s because he argued that it was necessary to organise workers, still does not accept the absolute centrality of the working class for the Indian revolution and the transformation of society.

This not only reveals itself in his adherence to the idea of the four-class bloc for the democratic revolution against feudalism, but also in his idea that the tribals have an interest in fighting for some kind of regional autonomy. He said in a recent speech: ‘People want the development of Chattisgarh. It’s the democratic right of the people. Today the bourgeoisie and the petty-bourgeoisie of Chattisgarh are becoming more and more interested in the issue. The demand for their own state is becoming more popular among the peasants. That is why the working class has to take an active interest in the issue.’ [34]

The point is that as was said in Part One the only people who benefit from new states are the petit-bourgeoisie who get state jobs, and capitalist farmers who get state financial support. In this instance, the tribal peasants (almost certainly incorrectly) see a separate state as an opportunity to escape from the clutches of the non-tribal merchants and gain access to the market for their crops. When Niyogi says that the peasants’ support for a separate state determines the working class’s attitude, he is saying that the working class is not absolutely central to his politics.

The most serious danger is that this would provide conditions for the splitting of the workers on tribal/non-tribal lines if the tribal workers were led off to support a section of the ruling class It also means that, in practice, Niyogi does not put an absolute priority on building links with other workers and with generalising the workers’ struggle. When the official left federations called a general strike against proposed trade union legislation at the beginning of 1982, he refused to take part because it was organised by the CPI and the CPM. This sectarianism was mirrored in his speech to the All-India Steel Workers Convention which the CMSS organised in October 1982.

After starting with the usual gesture towards the industrial proletariat as the vanguard of the struggle, Niyogi then attacked the leaders of the left unions not only for being in league with the management, but also for ‘economism’. This turned out to mean fighting for increases in the bonus and basic rates, and for workers in one industry trying to catch up with rises achieved by workers in another. Instead he argued that the workers should pressurise management to increase production.

Now in a recession this argument has some force in as much as it is an attempt to fight redundancies and seize some control of the labour process from management. But Niyogi counterposed it to fighting over wage issues. In addition the CMSS are fighting against the mechanisation of the mines, not on the grounds of saving jobs, but because they argue that semi-mechanised labour is more productive. Whether or not this is true is besides the point. The real point is that Niyogi’s political line will direct the union into a ‘struggle for production’ on the grounds that-the workers are more patriotic than management and that this will increase the prestige of labour and root out corruption, laziness and irresponsibility amongst the workers. Rather than transforming capitalist society, the workers are supposed to become its purest members.

These politics constitute an immense obstacle to the development of the workers’ struggle. An obstacle because they work against the building of links between workers and the generalisation of workers’ struggles. Even supposing Niyogi is successful in implementing the battle for production perspective inside the CMSS, how can that be spread to workers in mechanised mines, let alone to the rest of the working class? It cannot, and even if successful would mean an accommodation with capitalism which would transform the CMSS into a mass reformist organisation.

In fact, it will probably never come to that, since Niyogi is faced with the absolute contradiction that the obvious representatives of the progressive national bourgeoisie with whom he is seeking to ally are the very mine managements whom he and the CMSS spend most of their time fighting. He gains his political influence because much of his politics fit the experience of the workers – their experience of racism against themselves as tribals, their recent experiences as peasants, their continuing links with the countryside, and so their very partial concept of themselves as workers. The upshot of his politics, if continued, would be to build a strong sectional union, with a reformist political perspective which will eventually lead it to align with some faction of the ruling class.

The tragedy is that Niyogi is a mass working class leader. He has led more successful mass strikes, and under worse conditions, than most union leaders alive. His personal integrity is beyond question, and the workers in the CMSS have won great victories against the management and the state. Yet eventually all this will be defeated if the political perspectives remain unchanged. The CMSS sums up in an acute form the main crisis of the Indian working class. They have shown immense bravery, imagination and fortitude in fighting their ruling class, but all this will be brought to nothing if a few basic political arguments are not won: the absolute centrality of the working class to the struggle, the consequent abandonment of the four-class bloc in favour of a socialist revolution and a workers’ state; and the necessity for solving the agrarian question through winning the argument with the peasants that their problems can only be solved through the victory of the working class.

Once these are won then the way is clear to begin the tasks of building links between sections of the class and to generalise experiences and struggles. The problem is that these arguments are not being made in the CMSS, or in the other independent unions. Indeed the only way to ensure that they are made at all is the existence of a revolutionary organisation, and that just does not exist at the present time. As the current wave of the recession hits India, this lack of any revolutionary organisation is becoming especially serious.

Indira Gandhi’s overwhelming electoral victory in 1980 appeared to have halted the political disintegration of the Indian ruling class. The ruling class dissidents joined together in the Janata party had fallen upon each other in factional fury, and with breath-taking naivety had allowed themselves to become the victims of another display of Indira Gandhi’s tactical virtuosity. [35] She had already isolated and comprehensively obliterated the factions of her own party who had attempted to ditch her following the 1977 defeat. To all appearances the Janata regime had been a temporary aberration and she was back in command.

The appearances deceived. Despite much whimpering from the left about the danger of ‘authoritarianism’ there was never any possibility of recreating 1975 in 1980. The left were incapable of distinguishing between violent repression, which is normal, necessary and routine for the survival of the Indian ruling class, and an institutional dictatorship of a part of the ruling class, which was the reality of the Emergency. The Emergency failed because the social base of the regime was too weak to control the rest of the society. It could not now be repeated with any hope of success. After 1980 Indira Gandhi’s role was to use her political predominance to patch up the political fissures in the ruling class, while attempting to find some way of expanding the economy out of the recession which would relieve the pressure on the coherence of the ruling class. Her problem here was that the state has now even less effective influence than it had before. The state capitalist section of the economy is now stagnant, while private capital or sections of it, is bounding ahead. In time this will have a political effect, as Indira Gandhi’s social base will have to cede its predominant position to private capital. The behaviour of the Bombay textile employers in rejecting the government’s attempts to settle the strike in November 1982 may be a forerunner of this shift.

So while the Emergency was an attempt to crush the power of the local bosses, since 1980 Indira Gandhi has been reduced to arbitrating between factions in state-level Congress (I) units. This factionalism has spread like a plague virus, with no state Congress (I) government .being safe from plotting for even two months. In some cases states have had three chief ministers inside twelve months. Eventually this has told on the electoral prospects of the Congress (I) as the gap between rhetoric and reality has become too great to be avoided. In the elections in the southern states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh in January 1983, the Congress (I) suffered heavy defeats in an area which had remained solid even in 1977.

For the opposition this has been a case of recovery from the brink of death. In Andhra Pradesh, the election was won by a regional party formed by the local film star, a populist whose party is mainly comprised of dissident Congress elections elements, and whose long-term prospects are not, therefore, very good. In Karnataka the corpse of the Janata party managed to struggle out of the grave to form the government with the aid of other opposition groups. But to get an idea of what is happening to ruling-class politics, it is necessary to set party labels aside for a moment.

Ever since the late Sixties there have been increasingly intense attempts to organise rich (ie capitalist) farmers on a political basis. The material basis for these attempts has been the spread of agricultural commodity production via the ‘Green Revolution’ and the consequent formation in most Indian states of large classes of capitalist farmers, frequently clustered in a few numerically large local castes. These existing pre-capitalist social ties have facilitated the formation of political parties, since they provide a ready-made means of mobilising small non-capitalist farmers and some agricultural workers behind the capitalist farmers. Since, by the same token, in any particular area a majority of agricultural workers are of a different caste or religion to the main body of capitalist farmers, then caste or religion is a routine weapon for the local ruling class in attacking the working class. [36]

The prototype of the so-called ‘peasant parties’ was the BLD of Charan Singh, a long serving ex-Congress politician. This party was principally based on capitalist farmers in the northern states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Haryana. Although it suffered from the factionalism which accompanied the Janata collapse it remains a significant political force. Since 1980 there have been a number of ‘farmers agitations’ in important states. These were movements of capitalist farmers in favour of higher prices for their crops, but they managed to mobilise very large numbers of small non-capitalist farmers behind them. They were not, in the main, organised by established party politicians. Indeed they had the parties, including the left, running along trying to jump on the bandwagon. However, the basis for at least part of the opposition success in Karnataka was laid on this class, and in general it is now clear that there is a material basis for the political organisation of capitalist farmers on a national extent if not in a national party.

This class forms one leg of a possible ruling class alternative to Indira Gandhi’s regime. The other leg is the neo-fascist party, the BJP. This is a reincarnation, slightly amended, of the Jan Sangh which became part of the Janata. It is in reality a classic neo-fascist party, with an authentic fascist ideology and programme and a classic fascist mass base amongst the petit bourgeoisie. Its real muscle comes from one of the elements which promoted the formation of the Jan Sangh in 1951, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS – the title roughly means national self-help organisation), a mass para-military organisation of the Hindu chauvinist petit-bourgeoisie, formed in 1925. [37] The RSS provides the BJP with its cadres, and makes a speciality of organising communal pogroms. [38] The interests of the BJP’s base are quite compatible with those of the rich capitalist farmers, since the aggressive national chauvinist policy the BJP would almost certainly follow if they came to power would provide immediate benefits for capitalist farmers. In the face of a militant working class such an alliance would, in certain circumstances, offer benefits for private capital with the RSS being able in the manner of the Nazis to offer a means of crushing a militant working class.

One major barrier to the growth of fascism in India has been the hostility that the RSS’s Hindu chauvinism has aroused in the south. The south is not only ethnically distinct from the north, but the southern languages are totally dissimilar to Hindi, the RSS’s candidate for a national language. In the early sixties the attempt to replace English as the language of the national state provoked major riots in Madras and provided one of the levers which brought a regionalist party (the DMK) to power in the state of Tamil Nadu in 1967. To succeed on a national basis the RSS and BJP had to overcome this problem.

Since 1980 there has emerged evidence that there is an attempt to do so through the adoption of a much more sophisticated strategy than the one previously employed. Where the local ruling class groups use caste or religious communalism in the class struggle, the RSS is intervening. They offer their organisational skills which are far superior to anything that the locals possess, and are thus attempting to incorporate a wide range of local extreme right groups into their national perspective.

In Kerala, the RSS have been able to gain a firm foothold by forming an alliance with the National Democratic Party, the political wing of the rabidly anti-communist Nair Service Society (the Nairs are a large caste group in Kerala and the NSS is the instrument of the right-wing leadership in the caste). Kerala, as well as being one of the main bases for the CPI and CP(M), is also riven on communal and caste lines. There are large Muslim and Christian communities as well as Hindu caste groups which organise politically, and a frequent point of friction is the reservation of government jobs for the members of various communities. The RSS, being fanatically anti-Muslim as well as anti-communist, has been able to enter Kerala on this basis by providing street-fighters to attack CP(M) cadres, which it has been doing for the past couple of years. At the beginning of 1982 it cemented its relationship with the NSS by forming a front organisation, the Vishwa Hindu Sammelan, to save Hinduism from the communists and the Muslims (and by implication save the Hindus’ jobs). [39]

The RSS has used a similar tactic under a different title (the Vishwa Hindu Parishad) in Gujarat [40] (against untouchables), in Maharashtra [41] (also against untouchables) and in Tamil Nadu [42] (against Christians). In each case they have used their front organisation to intervene in an existing local communal dispute in an attempt to draw the local right wing organisations under their influence. So far their success has been variable, but they possess formidable organisational abilities and a national perspective which local groups cannot match. Using front organisations also allows them to attract people with similar politics who for historical reasons may happen to be in Congress or other parties.

They have used this particular tactic in Assam, where their politics fit in perfectly with the anti-foreigner, anti-Muslim nature of the regionalist movement. [43] Although they were not instrumental in starting the campaign in 1980, recent reports (such as in the Guardian on March 29th 1983) suggest that the RSS has gained sufficient strength inside the regionalist movement to seriously threaten attempts by a section of the leadership to do a deal with Indira Gandhi which falls short of their maximum demands.

The threat of this expansion of the parties of the right is obvious. At the best it threatens to disrupt the workers’ struggles by dividing them on caste and communal lines. At the worst it could result in the formation of an ultra-right wing regime with a mass base in both urban and rural areas. This could spell disaster for the workers of the entire Indian Ocean region, let alone India itself, given the aggressive military posture that such a nuclear-armed regime would adopt.

The tragedy is that the left cannot combat this expansion of the right. Their class alliance politics force them to tail behind the rich farmers’ movements, unconditionally support their demands for higher prices. Their reformism means that in practice they accommodate to the caste divisions that they find around them. Caste divisions means that local caste groups frequently align themselves with a particular party. So, for instance, if in a particular area caste Hindus support the BJP, it is not too difficult for the CPI to organise amongst the untouchables. This provides the CPI with a ready-made vote, but it forms an immense barrier to them influencing worker members of the Hindu caste, since they are presented as the party of the untouchables. The CPI and CP(M) have fallen into the trap of Gandhian politics – instead of ‘Down with caste’, they call ‘Down with caste oppression’. The slogans are in fact radically different. The second position wants to reform caste, the first wants to abolish it. Workers’ unity can only be achieved by a call to abolish caste (and all other communal divisions like religion and tribe), because only in that way will it be possible to decisively undermine the ability of caste-based sections of the ruling class to divide the working class.

All of the problems facing the Indian working class cry out for the intervention of a revolutionary party. No such organisation exists. The objective conditions for building such a party do exist: the level of working class struggle, the potential core of such a party from among the members of the scattered socialist circles, the militant workers in the independent unions, from activists in Maoist groups in the rural areas where they have rebuilt local bases.

Such a party cannot be created at once from people whose politics are at present so divergent. But an organisation which campaigns for building such a party, on the basis of the absolute centrality of the working class, and which translates that perspective into its own practice, can be built now. There are the necessary handful of people who have the politics to begin the long and arduous task. We shall have to deal with the specifics on another occasion. But about what the task is for revolutionary socialists in India there can be no doubt.

1. South Asia is the region comprising the contemporary states of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Afghanistan, and Bhutan

2. After 1857 British rule in India had two purposes. The economic purpose was that as India had a balance of payments surplus with every industrial country apart from Britain, the foreign currency earnings were transferred to London to support British finance capital. The 1930s depression, which cut the prices of Indian agricultural exports by up to 50%, ended all that. The second purpose was military, as the Indian army underpinned the empire in the east. The Japanese victories of 1942 destroyed the British military position, and they were only saved by American victories in the Pacific. Thus by 1945 the reasons for British rule in India had disintegrated.

3. There were other parties which represented sectional interests, notably the Scheduled Castes Federation of Dr B.R. Ambedkar; the Hindu chauvinist Hindu Mahasabha; and after his expulsion from the Congress in 1940, the Forward Bloc of Subhas Chandra Bose.

4. Foreign investment has always played a major role since independence, usually in the form of ‘collaboration agreements’ with local firms. While this has often meant the acquisition of semi-obsolete technology, and the foreign collaborator has habitually made large profits out of the deal, it has also meant that the Indian collaborator has usually achieved a large expansion of its capital values (see Brian Davey, The Economic Development of India, p. 146). This illustrates the danger of attaching the tag of ‘imperialism’ to a process which materially contributes to the expansion of capitalism in India

5. See Section Three, on the miners of Chattisgarh.

6. This was the occasion of the first Congress split, when a group of regional bosses known as the Syndicate attempted to overthrow Indira Gandhi. They found themselves completely outmanoeuvred.

7. The one exception was the case of the railway workers, where organisations of skilled workers, run by the workers themselves, had existed for a number of years.

8. Gail Omvedt, Maharashtra strikes, in Frontier (Calcutta), April 24th 1983.

9. The 1981 Census gave the proportion of workers in the total population as 37.5%. However, this is a crude figure which further analysis is likely to reveal as containing a number of simple commodity producers (i.e. petit-bourgeoisie).

10. For an account of how M.N. Roy spent the early 1920s stuck in Berlin, reliant on a bunch of imbeciles and crooks to act as couriers to India, see Muzaffar Ahmad, Myself and the Communist Party of India (Calcutta, National Book Agency, 1970). Ahmad was a young radical in Calcutta, trying desperately to get in touch with the Comintern.

11. Many of the CPI and CP(M) leaders were recruited in this way. See, for instance, the autobiography of one of the best of the CP(M) leaders, E.M.S. Namboodiripad, How I Became a Communist (Trivandrum, Chinta Publishers, 1976).

12. These included the Socialist Unity Centre in Bengal, which combines a state capitalist analysis of Russia and lunatic Stalinism on every other front, and the Lai Nishan Party in Maharashtra, which is consistently anti-parliamentarian and possesses a mass base, but because it has no overall perspective on how to achieve workers’ power is consistently pulled towards centrist politics.

13. The most serious consequences were in Bengal, where the CPI had built a mass base through the Tebhaga peasant movement in 1943–46. This ought to have given them the opportunity to fight communalism – instead they were impotent in the face of mass slaughter organised by the religious communalists. It was a stunning indictment of CPI politics.

14. For details of the faction fights, see my Telengana Movement 1944–51 or Mohan Ram, Indian Communism, Split within a Split (New Delhi, Vikas, 1969).

15. The only exception was between 1969 and 1971, when Indira Gandhi needed the CPI and CP(M)’s parliamentary votes to beat off the Syndicate. The left parties thought that their hour had come, but after using them to push through populist legislation like bank nationalisation and abolition of subsidies to the princes, she turned on them with stunning viciousness.

16. Mohan Ram, op. cit., p. 73.

17. Avtar Singh Malhotra, What is the CPI? (New Delhi, CPI, 1970), p. 55.

18. This was explicitly revealed when the CPI won the 1957 elections in Kerala state. Until 1959, the local ruling class, with the connivance of the central government, ran a mass campaign to destabilise the state government and attract intervention from the centre, which in due course took place. This was at the same time that the CPI gave its seal of approval to Nehru at the Amritsar Congress!

19. Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) (Bombay), July 1st 1978.

20. These usually appear as ‘encounters’ in single paragraph reports in the Indian press.

21. Anti-labour offensive in Haryana, EPW, March 18, 1978.

22. Mohit Sen, Indian Rank and File, Socialist Review, June–July 1980.

23. Trade union murders in Dhanbad, EPW, March 10, 1979.

24. See my All out in Bombay, Socialist Review, June–July 1982.

25. The irony is that the only language spoken to a countrywide extent is English. Hindi, the ‘national language’, apart from being an invention of grammarians, is a national language only in the same sense that it is the language of the national bureaucracy, the Indian Administrative Service.

26. Maharashtra Sugar Factories Strike, EPW, December 1, 1979.

27. A coherent exposition of the CP(M) version of this line can be found in Prakash Karat, Language and Nationality Politics in India (New Delhi, Orient Longmans, 1973).

28. Cudgel of Chauvinism or Tangled Nationality Question?, EPW, March 15 1980; The Left and Assam, Frontier, June 20 1981.

29. See Rajahara Massacre, in EPW, June 11th 1977; Dalli-Rajahara Mines – Victory for Workers, in EPW, July 9 1977.

30. The point is that tribes, like many of the untouchable castes, remain distinct. Mundas, Oraons, Bhils and Gonds, for instance, are all tribes, but they do not necessarily recognise a common interest, except at the level of bourgeois politicians. There is no generalised ‘tribal consciousness’, which some on the left have tried to point to as a parallel with black consciousness in South Africa or the USA.

31. For accounts of some of the tribal revolts, see Rebellious Prophets, by Stephen Fuchs (Asia, New Delhi, 1965), especially Chapter 2

32. These are reserved seats, not separate electorates, i.e. the MP must be a tribal, but the whole electorate votes. This gives unbounded scope for factional dealing. There are similar seats for untouchables (the ‘Scheduled Castes’).

33. For an excellent report on the actuality of the CMSS, see John Rose’s article in Socialist Worker of January 8 1983.

34. (Emphasis BP).

35. When Indira Gandhi first became prime minister, the party bosses treated her as a female stereotype. When she belied this by putting them to the sword in the 1969–72 faction fight, they assumed that she was in fact like one of themselves. Their attempts to deal with her on this basis during the 1979 government crisis had disastrous results as she yet again outmanoeuvred them in a devastating fashion.

36. Biharsharif Carnage – A Field Report, EPW, May 16 1981.

37. The RSS has a membership of hundreds of thousands, drawn predominantly from urban petit-bourgeois – merchants, artisans, salaried employees. Its aim is a state and society based on ‘Hindu culture’ and philosophy, and the undoing of partition by conquest if necessary.

38. See for just one recent example Guilty Men of Meerut?, EPW, November 6 1982.

39. Kerala – Political backdrop to Trivandrum Riots, EPW, February 12 1983.

40. Communal violence in Ahmedabad, EPW, January 23 1982.

41. Maratha melava, EPW, February 6 1982.

42. Communal clashes in Kanyakumari, EPW, April 24–May 1 1982.

43. Contending Chauvinisms, EPW, May 8 1982.

ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 16 April 2015