INDONESIA

ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism 2:80, September 1998.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Copied with thanks from the International Socialism Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

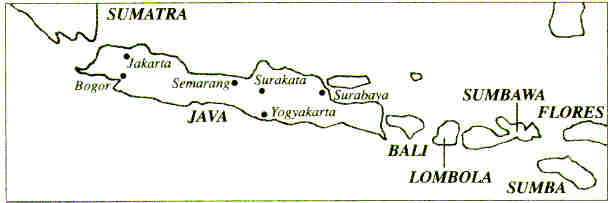

The story of what has happened in Indonesia is the best possible answer to all those who write off Marxism as irrelevant to the modern world. Such people say that the working class is disappearing. In Indonesia, in just 30 years, the working class grew from less than 10 million to 86 million – far more than the entire world working class at the time Marx and Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto. Such people said that the so-called miracle Tiger economies were immune to the traditional booms and slumps of capitalism. In Indonesia the economic slump was more unexpected and catastrophic than Marx himself could have imagined. Such people have been saying that the events of May 1968 in France were a blip on the liberal historical process and will never happen again. In Indonesia, a country four times more populous than France, students have led a mass revolt that is every bit as shattering as that of 30 years ago. In 1968 the revolt spread across Europe and further afield. Today the dictators and governments in Malaysia, Thailand, South Korea and elsewhere are trembling in fear.

Those who write off Marx say that the only way to achieve reforms is to elect educated liberals to parliament and wait for improvements to be handed down. In Indonesia all the evidence of the past few months shows that such liberals are both unwilling and incapable of delivering reforms, and that only when the masses take to the streets do reforms become possible. Those who write off Marx also say that the independent organisation of the most class conscious elements of the working class is not needed under liberal democracy. In Indonesia liberal democrats have stirred up racism, courted favour with international capitalism and stuck their noses into the trough of corruption and greed. Only the organised working class has an interest in fighting racism and the system that is based on profit, not need, and only the organised and politically conscious working class can challenge for state power and seize what is rightfully theirs – the wealth they have produced.

’Indonesia is rich in raw materials yet the people live in misery. The people can no longer afford to eat or buy medicine. This is all the fault of the system – this is what we have to smash.’ These words were spoken by student leader Cecep Daryus at a rally shortly before President Thojib Suharto was toppled on 21 May 1998. A few months earlier, the young man would probably never have thought of such words, let alone dared to say them out loud. What was amazing about the overthrow of Suharto, as so often with the fall of dictators, was the speed with which it happened. The anger which exploded to overthrow the dictator who had ruled his people without mercy for 32 years had in fact been building up for some time. This article first looks at the mounting economic crisis facing the old regime and the growing resistance to the dictatorship since the virtual annihilation of opposition in 1965. Secondly, it describes how the uprising unfolded and analyses the main forces of opposition. Thirdly, it outlines the enormous obstacles facing the new government as it tries to grapple with deepening economic crisis and an awakened people, and sets out what steps need to be taken by organised labour and the left to ensure that the revolutionary period Indonesia has entered is pushed forward and the suffering of the masses finally ended.

President Suharto came to power following a military coup in 1965 carried through with such relentless violence that between half a million and a million Indonesians were wiped out within a year. For 32 years, from the moment he butchered his way to power until a few weeks before his overthrow, he was the darling of the West. He offered loyal support against the ‘red peril’ in the region, a huge market for arms sales, and a massive source of profits from the exploitation of the country’s vast natural resources and huge pool of cheap labour.

|

INDONESIA |

|---|

|

Suharto was not so popular at home. His rule over the world’s fourth most populous country (200 million people) was maintained by brutal repression. All opposition political activity was banned. Peaceful protesters, trade union activists, all those who tried to organise independently were routinely imprisoned, tortured and sometimes assassinated. When Portuguese colonial rule collapsed in East Timor in 1975, the Indonesian army illegally occupied the country: 200,000 people, one third of the population, were killed or died of starvation as a result. Thousands of people on the islands of Aceh and Irian Jaya (site of the world’s largest gold mine) were also slaughtered over the years for daring to seek independence.

Suharto’s government, based on his organisation, Golkar [1], and two ‘permitted’ parties, was simply a cover for autocratic military rule. Half a million troops were deployed throughout the country, right down to village level. The military had authority over political, social and economic matters, as well as security. And the military was supplied, trained and even financed by the West, particularly the USA and Britain.

The West’s loyal support of Suharto and the military’s high profile in Indonesian politics have their origins in the post-independence period. When Indonesia finally won formal independence from the Dutch in 1949, the country was led by President Achmed Sukarno, a petit bourgeois nationalist. Sukarno’s ideology for running the new Indonesia was based on the five principles of pancasila: belief in God; national unity; humanitarianism; people’s sovereignty; and social justice and prosperity. For Sukarno, pancasila meant uniting nationalists (the intellectuals, landlords and business people); the Indonesian Communist Party (the PKI) which had the support of the small working class; socialists; Islamists and religious activists. To secure the army’s loyalty, Sukarno allowed it to have direct involvement in politics and the running of government. The army also became deeply involved in the economy when it secured most of the Dutch businesses nationalised by the Sukarno government.

The Western imperialist powers hated Sukarno for helping to found the Non-Aligned Movement in 1955 which aimed to counter the influence of the Cold War powers and to oppose nuclear proliferation. The Western powers were also suspicious of Sukarno’s attempts to co-opt the mighty PKI, mistakenly fearing that he would not be tough enough on them. The United States in particular was determined not to let another huge country in Asia ‘fall’ to the Communists, as had happened in China in 1949. Following a policy drawn up by Stalin, which directed Communist parties to collaborate closely with bourgeios nationalists, the PKI accepted about 60 seats of 261 in the appointed Assembly. The PKI agreed to subordinate the needs of workers to the needs of national development and security. So it did not protest when strikes were banned, relying instead on militant anti-US imperialism to maintain popular support.

The PKI had no need to sacrifice its independence. In the elections of 1955, it won 6 million votes and by 1965 was claiming 3 million members. Its associated trade unions, peasants’ unions and women’s and youth organisations claimed at least 10 million members. If the PKI had fought for the emancipation of workers instead of snuggling up to nationalists and capitalists, it could have led its mass following to challenge for power. Instead it left itself vulnerable to attack. The crunch came with a small failed coup on 1 October 1965, which the military falsely blamed on the PKI. The army, led by a little known Sukarno-appointee, General Suharto, then organised a counter-coup with the backing of the US, Britain’s Labour government and Australia, and unleashed one of the worst massacres the world has ever seen. The PKI was unprepared and remained to the end unwilling to break with Sukarno and what it believed were ‘pro-people’ elements in the army. On 10 October, while its supporters were being rounded up and executed, the PKI’s Central Committee instructed all members to ‘fully support the directives of President Sukarno and pledge themselves to implement these without reserve’. In the face of such submission, the organisation was destroyed in the violence that followed. Every single one of its leaders was executed. Hundreds of thousands of members were slaughtered, the names of many supplied by the CIA. Virtually every radical element in the country was eliminated, either by death or imprisonment.

For the West, the new Indonesian president Suharto was a hero who had smashed Communism and would slavishly serve imperialism. The importance of Suharto’s victory to the imperialist powers was summed up by Richard Nixon in 1967, a year before he became US president: ‘With its 100 million people and its 300 mile arc of islands containing the region’s richest hoard of natural resources, Indonesia is the greatest prize in South East Asia.’

The US and Britain ensured that for the next three decades their man in Jakarta was never short of the weapons of repression. US companies supplied 90 percent of the arms used by the Indonesian army when it invaded East Timor. The following year the US doubled military aid to the country whose invasion of a neighbouring state had been condemned as illegal by the United Nations. Between 1982 and 1984 it supplied the dictator with $1 billion worth of weapons. Even when Congress restricted military training and arms sales to Indonesia in 1992, the Clinton administration found ways of circumventing the restrictions. Meanwhile, both Labour and Tory governments in Britain ensured that Hawk aircraft, Scorpion tanks, water cannon, and a huge range of guns and other weapons were supplied, with payment guaranteed by the British taxpayer. New Labour’s ‘ethical’ foreign policy made no dent in the sales: even as the Suharto regime lashed out with British weapons against Indonesians protesting against growing poverty in early 1998, sales of British weapons, including Hawks, continued unabated.

From the moment of Suharto’s victory, Western multinationals also feasted on the profits to be made in Indonesia, particularly after their man opened up oil, gold, tin, copper and rubber for joint profit making ventures. As the country industrialised, the multinationals brokered deal after deal, always through Suharto’s family and his cronies, to make money out of sweatshop labour and the financial system. Factories sprang up everywhere producing goods for export, goods such as trainers that sold for the equivalent of three or four months pay of the workers who made them. In the boardrooms of Indonesia’s conglomerates men and women were feted by Western businessmen who now condemn them as Suharto’s cronies.

For more than 30 years Suharto was hailed by the West as a genius who had painlessly modernised his country and brought wealth to his people. It was true that Indonesia had experienced strong economic growth (average annual growth of GDP was over 6 percent throughout the 1980s and 7.6 percent between 1990-95). Annual growth in income per head did average 4.6 percent from 1965 to 1996, increasing per capita income from $270 to $1,080, and there was a general fall in absolute poverty and an expansion of the middle classes. [2] But none of Suharto’s Western admirers would admit that most of the wealth went into the pockets of Suharto’s friends and the multinationals, and that the economy was already beginning to show signs of weakness because of cronyism and intensifying competition from other exporters in the region. They certainly didn’t advertise the awkward findings of the UN Development Programme, which showed that in 1990 nearly 15 percent of the population would not reach their 41st birthday, that 38 percent of the population lacked access to safe water, that 15 percent of people lived on less than a dollar a day, and that in 1995 half a million children died before their first birthday.

The ‘miracle’ of Indonesia’s economy was not as it appeared on the surface: economic slump was just around the corner. And the people who had suffered so much repression and exploitation on the promise of endlessly expanding national prosperity were about to explode in anger.

By 1997 Indonesia’s economy had grown to become the twenty-third largest in the world. But its long boom was beginning to falter. The reasons for the decline were similar to those affecting all the Tiger economies in South East Asia-rapid growth based on low wages and excessive borrowing, followed by overproduction, falling profits and debt crises. Indonesia’s problems were particularly bad because its exports were being squeezed by Japanese competition in the more sophisticated goods and Chinese competition in the less sophisticated goods. Even its low labour costs were suffering from competition: companies such as Levi Strauss and Nike were finding even cheaper labour elsewhere. The particular problems faced by Indonesia were also partly caused and certainly exacerbated by Suharto’s intransigence, greed, corruption and control of much of the economy.

Forbes, the US magazine, put Suharto third in its ‘king or tyrant’ category in 1997, estimating him to be worth $16 billion and his whole family $46 billion. [3] The family controlled most of the main conglomerates in the country, including Citra Lamtoro Gung Group, Bimantara Group and Humpuss Group, ran around 100 ‘charitable’ foundations, and had shares in more than 1,200 companies. Among the industries they dominated were car manufacture, chemicals, media, telecommunications, hotels, shipping, gasoline, airlines, retailing, construction, toll roads, power plants, real estate and water.

Alarm about the Indonesian economy became public in August 1997, when the rupiah was allowed to float and Bank Indonesia introduced high interest rates. The following month the rupiah began to freefall, as did the stock exchange. The government froze infrastructure projects, but couldn’t stop the rot. In October the World Bank, IMF and Asian Development Bank offered Indonesia a $37 billion rescue package, the second largest deal in history. Still the problems mounted. In November 16 banks closed and thousands of people’s savings were frozen. Suddenly everyone began to notice that all was not well with the recently praised Indonesian economy. In late 1997 Western investors started complaining that the cost of paying off Suharto’s family and cronies was adding up to 30 percent to some deals. A diplomat said at the time, ‘They have started the feeding frenzy before the downfall.’

The international ruling class began to turn against Suharto. It was becoming increasingly impatient with the corruption of Suharto’s ruling elite, which had become an intolerable barrier to the free exploitation of the Indonesian economy by multinationals and was provoking a potentially infectious uprising in the region. Their frustration was summed up in the IMF package, which insisted on the dismantling of all state sanctioned monopolies and restrictive trade practices.

By the beginning of 1998, the rupiah had collapsed to 10,000 to the dollar (from 2,400 in August 1997) after the budget breached IMF terms. Almost overnight the true extent of the crisis became apparent. Foreign debt stood at $200 billion, rather than the official $117 billion. Private sector debt was around $65 billion. Up to 80 percent of corporate Indonesia was technically bankrupt. Now Suharto had no choice but to turn to the IMF, which offered a $43 billion recovery package, attached to an ‘austerity programme’ and the scrapping of 12 major infrastructure projects. Suharto was not used to such treatment from his Western patrons, who were in effect asking him to dismantle his family’s economic empire. He did everything he could to avoid implementing the IMF’s demands, believing he would get the money in the end.

By May 1998 the rupiah had lost 80 percent of its value in a year. Imports, including rice and other key produce that Indonesians depend on for survival, became ruinously expensive. One industry association estimated that imports dropped from a pre-crisis level of $2.5 billion per month to around $100 million by early 1998. Foreign exchange reserves almost disappeared and the central bank began to print money recklessly, threatening hyperinflation. Most of the country’s 200 commercial banks were exposed as illiquid, and some could not cash cheques. The huge foreign debt could no longer be serviced without rescheduling. The level of domestic debt was bringing production to a standstill. Even the massive state owned Pertamina, the oil and gas monopoly, defaulted both domestically and abroad, and was forced to halt production.

Ordinary Indonesians were being made to pay for the $43 billion IMF bail out, but the Suharto family (which was worth almost the same amount as the bail out) was being let off the hook. When the government announced in early May 1998 that electricity and petrol subsidies would have to be removed to save 27 billion rupiah, some Indonesian newspapers asked why the government had been able to find 103 billion rupiah to rescue the banks owned by its cronies so easily. The rupiah’s exchange rate crash meant the oil industry was making superprofits overnight, yet none of the benefit was being passed on to consumers. Such disparities fuelled unhappiness about the glaringly obvious inequalities between classes and regions. The ratio between the highest and lowest income groups rose from 3.8 in 1985 to 6.2 in 1993 [4], and rose even more sharply in the following years. The eastern part of Indonesia, accounting for 40 percent of the land area, was receiving only 7 percent of private investment. The new office blocks, luxury department stores and other signs of wealth in Jakarta were standing side by side with slums: nearly half the population in the capital had no drinkable water or primary health services. A few miles from the modern cities were peasant communities hardly touched by the 20th century – a classic example of what Trotsky described as combined and uneven development.

As the crisis deepened, survival for the masses became increasingly hard. Food prices were soaring while wages were frozen. In less than a year the price of rice had risen by 38 percent, cooking oil by 110 percent, chicken by 86 percent and milk by 60 percent. Subsidies that are the difference between life and death for millions of Indonesians were being cut or threatened. Basic goods and medicines were in short supply. And every day people were being laid off as companies crashed. From January 1998 onwards, an average of more than 2 million workers lost their jobs each month. On top of all this, there was a crippling drought related famine in vast areas of the country, and an additional million children faced being withdrawn from school because their parents could no longer afford the fees.

In early May the situation deteriorated further as the IMF ‘reforms’ began to bite. Train fares were doubled and it was announced that electricity prices would go up by 60 percent and water rates by 65 percent. The price of fertilizer, crucial for millions of people in the countryside, had risen by 12 percent in a month. Everywhere people were getting hungrier and poorer by the day.

The deepening economic crisis was being matched by a growing political crisis. Suharto was facing a people who had slowly and painfully begun to recover from the terrible defeat of 1965. The first major sign of the revival of resistance came in 1974 when a million people spilled onto the streets during widespread student protests. The most significant development, however, was the emergence of a huge working class. Tens of millions of people had been drawn into manufacturing and other industries, where they were exploited at incredible levels. Yet they were also brought together as workers, and as the 1980s progressed they began to use their collective strength to strike for better wages and working conditions with some success.

In 1973 trade unions had been forced to merge into a federation whose president was a former military intelligence officer. Despite this, some sections of the federation still tried to represent workers’ interests, so the government replaced it in 1985 with the All-Indonesian Workers’ Union (SPSI), which was dominated by business people and Golkar representatives. Faced by mounting illegal trade union activity, the government was forced to end the ban on strikes in 1990, after which the number of strikes rose steadily. In 1995, 365 strikes were registered. In 1996 the number rose to 901, nearly three a day, involving around half a million workers.

By 1997 there were 20 million workers in the major urban centres, with a further 66 million workers elsewhere. Around 30 million were working in the service and minerals sector. [5] According to Suharto’s government, 74 percent of foreign exchange earnings were derived from the non oil and gas sectors: of this, manufacturing contributed more than 63 percent. Women were particularly affected by the migration to the towns. By 1997 they made up around 40 percent of workers, compared with 33 percent in 1980. Most worked in the worst factory jobs, often in special export zones, where they made up nearly 90 percent of the workforce. Women became increasingly prominent in strikes and as union leaders.

Despite the very real economic gains made by workers (manufacturing wages rose by an average of 5.5 percent a year between 1970 and 1991), their wages were still pitiful, even compared to other developing Asian countries. The average wage was 20 US cents an hour in 1994 compared to 54 US cents in China.

Although the level of strikes rose, the political consciousness of workers remained low. Most strikes were confined to immediate economic demands, such as wage increases to the legal minimum level, or transport allowances. In 1993, after Marsinah, a young woman active in an industrial dispute, was brutally murdered and mutilated a wave of strikes spread, building support for the new independent trade union SBSI (the Indonesian Prosperous Trade Union) which had been formed in 1992. In February 1994 Muchtar Pakphahan, the SBSI’s leader, called a nationwide one hour strike and thousands of workers took part. A month later there was an explosion of strikes in Medan, the country’s third largest city, which led to still more daring demands. The SBSI organised a virtual shutdown in the city involving tens of thousands of workers walking out of 70 factories. The demands included big wage increases, the right to organise and operate through the SBSI, an investigation into the death of Marsinah, and government intervention to reinstate 380 workers sacked at a match factory. As a result of the action, Muchtar Pakphahan and many other SBSI activists were thrown into jail. In 1995 another independent trade union, the PPBI, was formed, led by a 23 year old woman, Dita Sari. [6] It organised many strikes in textile and other factories. Its leaders were jailed too, including Dita Sari for six years.

By 1996 dissatisfaction with the Suharto regime was spreading to sections of the ruling and middle classes, who were being excluded from the profit and corruption bonanza by Suharto’s cronies. Even Megawati Sukarnoputri, the timid daughter of Sukarno and leader of the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI), one of the two parties ‘authorised’ by Suharto, began to speak out. Her mild criticism won immediate and enthusiastic mass support. So Suharto fostered a rival PDI faction led by Suryadi, who was then ‘elected’ PDI leader in June 1996. When the new leader tried to take control of the party headquarters in July 1996, Megawati’s supporters barricaded themselves inside the building, while mass rallies were held outside, bringing together a wide range of opposition forces. On 27 July the military attacked the headquarters, sparking off widespread riots in Jakarta. The crowds burned down 22 buildings, including police and army offices, banks and luxury car showrooms.

In the following eight months hundreds of political activists were imprisoned and popular discontent increasingly disintegrated into attacks on ethnic minorities. The gloom was shattered by a new surge of activity before and during the rigged parliamentary elections of May 1997. Mass demonstrations involved hundreds of thousands of people. Protesters broke through army barricades. There was widespread rioting, particularly by the urban poor and the youth. Up to a million people occupied the streets in parts of greater Jakarta on at least two occasions. Radical anti-Suharto slogans emerged and towards the end of the campaign open street fighting broke out.

Protests at varying levels were mounting throughout the country. They included strikes, large demonstrations, and attacks on police stations and government offices. In April 1997 a wave of strikes erupted across the industrial belts of Jakarta and Surabaya in protest at the minimum wage level. Then Nike workers went on strike for four days, beginning with a 10 kilometre march by 13,000 workers. After management reneged on an agreement which had brought the Nike workers back in, a second, more violent strike began. Workers smashed all the windows of the company and destroyed cars. The demands, albeit minimal ones, were suddenly met. In June bus drivers struck for two weeks in Jakarta and Bogor, causing widespread chaos. The strike quickly spread to cities across West Java and elsewhere. The same month the Barbie doll factory was shut down by strike action until workers’ demands were met.

The authorities responded with increased repression, particularly of trade unionists. In September 1997, for example, security forces raided the SBSI’s Congress, arresting 13 people, including foreign delegates. But they could no longer stifle union activity. In October workers at two major companies, IPTN (aerospace) and PT PAL (shipbuilding), staged huge strikes. The 16,000 workers at IPTN won a major victory over wages and other demands after a showdown with the boss, one B.J. Habibie who we shall meet again soon. Banners strung on the walls during mass meetings read: ‘Sack the corrupters and increase wages by 200 percent’ and ‘Bosses enjoy the good life, workers live in misery.’ In November 40,000 workers at the prestigious Gudang Garam clove cigarette factory went on strike for four days and won almost all their demands, including a 50 percent pay rise.

From the beginning of 1998, rioting and demonstrations spread across the 13,000 island archipelago. In January, the main form of protest was strikes. In February riots dominated, particularly in Java. From March, student protests took the lead, culminating in mass demonstrations and devastating riots in May. But throughout this period, all the forms of protest were happening at once. In fact, a classic revolutionary situation arose: the ruling class was no longer able to rule in the old way, and the ruled were no longer prepared to tolerate their rulers.

The rioting, fuelled by hunger, rising prices and unemployment, was spontaneous6, disorganised and violent. Because the people involved lacked any collective base or political leadership, much of the anger was initially directed at Indonesia’s ethnic Chinese community. This racist response to the economic crisis was stoked up by the government and by the main Muslim groups. On 9 February, for example, Suharto told a well-publicised meeting of Muslim leaders that ‘outsiders’ (Chinese) were responsible for the economic crisis. The same month Amien Rais, chairman of the 25 million strong Muslim movement Muhammadiyah, publicly blamed rich Chinese ‘parasites’ close to Suharto for the crisis. This followed the exposure of a document written by Special Forces Commander Prabowo Subianto, Suharto’s son-in-law, which called for a campaign to blame Chinese businessmen for the financial mess.

In this climate, ethnic Chinese traders in the villages dealing in staple goods became easy targets for hungry people. In the towns large supermarkets and luxury goods shops owned by ethnic Chinese were blamed for high prices. On 9 February, for example, ethnic Chinese shops and businesses on the eastern island of Flores were burned down and looted. In Pamanukan, a large town just 95 kilometres from Jakarta, days of rioting beginning on 13 February destroyed shops, restaurants, churches and schools associated with ethnic Chinese. There were also horrific mass gang rapes of Chinese girls and women, and many attacks on poor Chinese residential areas. [7]

However, much evidence has come to light since early 1998 that such attacks were orchestrated and carried out directly by the military. Small groups of men, either having the appearance of soldiers in civilian dress or accompanied by people in military uniform, arrived out of the blue in Chinese areas. They daubed houses with anti-Chinese slogans, encouraged people to join assaults they had started on terrified Chinese people, and invited men to participate in gang rapes. They also went through the streets shouting out anti-Chinese slogans, using language that exactly replicated anti-Chinese government propaganda.

Ethnic Chinese make up less than 4 percent of the population but control around 70 percent of the wealth. Twelve of the 15 wealthiest families are Chinese. [8] The vast majority of ethnic Chinese, however, do not belong to the billionaires’ club and struggle even harder than most Indonesians to make ends meet because of state sanctioned discrimination. As early as 1967 Suharto’s government set out its Basic Policy for the Solution of the Chinese Problem. Chinese newspapers were closed down. The use of Chinese characters in public places was banned. Chinese language schools were shut. Ethnic Chinese were banned from joining the military or government, and excluded from many state universities. They even had to carry special identity cards.

This ‘solution’ reflected the fact that ethnic Chinese have had a similar role in Indonesia to Jews in Europe in the past. Under the Dutch colonialists the ethnic Chinese were traders while the indigenous population was forced to work as slaves on large plantations. As the country industrialised, richer ethnic Chinese largely took over banking. They also bought hotels, department stores, factories, restaurants and many other businesses. At times of economic or political crisis, they have persistently been scapegoated by the authorities, as were Jews in Europe. During the mass killings that followed the military coup in 1965, ethnic Chinese suffered terribly, and Suharto and his friends regularly stirred up racist hatred in the following decades. The Muslim organisations also tried to gain support by vilifying ‘Christians’ (many ethnic Chinese Indonesians are Christian), or by stigmatising the Chinese explicitly. The main victims have been the poor ethnic Chinese: the rich learned from 1965 and most moved their main residences and much of their money abroad.

The rioting in early 1998, however, was not directed solely at ethnic Chinese particularly in areas where the working class was strong. In fact, as the crisis deepened, the focus of protests shifted towards the government and symbols of the ruling class (which did sometimes include Chinese businesses), especially when the protests had an organisational base such as student campuses or workplaces. In the industrial heartland of Surabaya in East Java, for example, violence spread through the city after riot police attacked student demonstrators in early January. Here banners were held aloft, saying ‘Reduce prices, smash the seat of power’. There was little sign of racism. In the following days, nearby cities were engulfed by riots, starting in Banyuwangi on 12 January and then moving on to Jember and Pasuruan. Shops were looted indiscriminately and security forces drafted in stood by unable to stop the waves of destruction.

Despite a total ban on all meetings and protests, and mass deployments of troops in the major cities, rioting and pro-democracy demonstrations spread like wildfire across the archipelago, and some strikes were held. In January, for example, workers in many factories went on strike when bosses refused to pay traditional holiday bonuses. Every day another group of protesters arrived outside parliament to air their grievances.

In February rioting broke out in at least 25 towns in east and central Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi and Flores, provoked by rising prices. According to Amnesty International, security forces responded in some areas with live bullets. Two people were shot dead in Brebes, Central Java, and two on the island of Lombok. Hundreds of protesters demanding political reform were arrested around the country as Suharto called on the military to take ‘stern action’ against demonstrators. On 12 February he said, ‘We cannot let them [demonstrators] hide behind the veil of democracy and freedom to express their opinions and then make good on their destructive and law violating ways’. [9] Students responded by pouring out of Jakarta’s University of Indonesia and Yogyakarta’s Gadjah Mada University to demand more political freedoms and human rights. Some students held hunger strikes.

On 11 March Suharto was ‘elected’ to his seventh consecutive presidential term, with B.J. Habibie as his vice-president. The 1,000 member People’s Consultative Assembly - 500 appointed by Suharto, 500 vetted by him – did not even hold a vote. There wasn’t much point as Suharto had not allowed anyone else to stand. Opposition leaders Megawati and Amien Rais decided to do nothing to upset the election ceremony, apparently willing to go along with Suharto’s month-long ban on all public meetings and demonstrations. Students reacted differently. The main campuses throughout Java erupted and student protests spread across the country. Lectures were cancelled and campus life across the archipelago became one long political meeting punctuated by angry demonstrations.

The activity was reflected in a proliferation of student newsletters across the country. The first and most prominent one, Bergerak!, was launched on 10 March at the University of Indonesia after a 1,500 strong rally. The four page daily was crammed full of news of student rallies, legal advice on the rights of demonstrators, interviews with activists, and satire directed against the authorities. Each issue sold out instantly.

As the student protests grew, army chief General Wiranto and education minister Wiranto Arismunandar warned students not to take the protests off campus. They were ignored: days later students took over the streets in Solo (Surakasta), central Java, and in two Sumatran cities. General Wiranto offered to talk to the students, but they refused, demanding to see Suharto instead. Many student activists were arrested and some disappeared, presumed dead. By April the clashes between students and police were growing steadily more violent. Students began throwing molotov cocktails and rocks at security forces, and set vehicles alight. In Yogyakarta police were injured and their cars smashed. Campuses became battlefields, surrounded by water cannons and bombarded with teargas.

On 11 April General Wiranto again warned students to stay off the streets, threatening more violence. A week later student leaders met cabinet ministers, following which Suharto ordered the army to be ruthless. Immediately riot police began firing rubber bullets. Every day more activists disappeared with a few reappearing telling stories of torture at the hands of the military. But each round of violence garnered support for the students. ‘Workers, professionals, housewives, even nuns began joining the students,’ reported Asiaweek. [10]

At the start of May Suharto announced that democratic reform would not be introduced until 2003, when his term was due to end. Students reacted immediately and organised increasingly large demonstrations. After some rallies on campuses students tried to take to the streets. Sometimes they managed to break through security force lines, and thus won much support from workers and the city poor. When security forces blocked students on campus, they provoked violent clashes, sometimes sparking off riots in nearby areas.

The temperature was raised further in early May when the government announced it would implement the IMF’s requirement to stop subsidising fuel and electricity prices. Immediately the cars of the rich and their chauffeurs began queueing for petrol, gridlocking the streets in some cities and forcing the poor to walk home-another sign of the rich being untouched by the ‘reforms’ while the poor suffered. On the morning of 4 May a huge student demonstration filled the streets of Medan. As soon as that was over, the city exploded into rioting, which lasted for three days. ‘Crowds formed, then rampaged. If troops or plainclothes police appeared, there would be a clash, or the crowd would dissolve down Medan’s streets and alleys followed by teargas and bullets. What they did not take, they torched’. [11] Troops closed the toll road. No ships left nearby Belawan harbour. Hundreds of shops were ransacked and similar numbers of cars left smouldering. Chinese shops and homes suffered worst. The bewilderment felt by the poorer ethnic Chinese was expressed by a 48 year old salesman: ‘We eat here, we sleep here, we even shit here-why can’t we be accepted?’ By the end of the three days, at least six people had been shot dead by troops and several had died in blazing stores. Hundreds of people were arrested, but most were released soon after. Riots breaking out elsewhere were also being met by security force violence. In Yogyakarta, for example, a young unemployed engineer who was simply watching rioters was beaten to death by soldiers.

Then workers began to stir. In the first week of May a wave of strikes broke out in the industrial estates to the west of Jakarta. Around 2,000 workers in ceramic and chemical plants in Tangerang and Serang struck, demanding wage increases to keep up with inflation. Some 1,200 workers at Surabaya’s PT Famous plant walked off the job. [12] Around 2,000 medical staff from Surabaya General Hospital demonstrated, demanding democratic reform. Mass demonstrations and riots were now breaking out across the archipelago, including in all the major towns and provincial cities. It was the beginning of the end of Suharto.

|

JAVA |

|---|

|

On 12 May the spark was lit that ignited the capital, Jakarta. Six students demonstrating outside the University of Trisakti were shot dead. Dozens were injured. The attack by the security forces was sudden and unprovoked, and no doubt ordered by the hardline element in the army under Suharto’s son-in-law Prabowo in a last ditch attempt to frighten people back to their homes. Around 5,000 students from Trisakti, one of the country’s most prestigious private universities, had been demonstrating against Suharto. They were blocking traffic as soldiers stopped them marching to parliament. For hours there was a stand off. At 5pm the students negotiated a solution: one row of students would back off for every row of police that did the same. But then suddenly the security forces charged, shooting into the ranks of the students with plastic and live bullets. From daybreak the following morning, thousands of students began arriving in delegations at the college, as did leaders of the democracy movement. Megawati spoke for the first time since the protests began. Amien Rais spoke too. Both called for non-violence, but it was too late.

An Australian socialist was there: ‘Students began to drift into the streets. Here they were joined by workers, the unemployed, the poor. Around Atmajaya University, in the heart of the city, office workers left their desks and came into the streets to express their support for the students. By nightfall, riots were spreading and the following day saw Jakarta in flames. Few corners of greater Jakarta were untouched. It was impossible to get to the airport, difficult to go anywhere. Some neighbourhoods looked like war zones’. [13]

For three days Jakarta was overwhelmed by protests, riots, looting and attacks on buildings. Vast numbers of the capital’s poor rioted, stealing what they could carry, burning and destroying anything that smacked of authority. Most stole food and clothing, which had become unaffordable in recent weeks, or ‘luxury’ goods such as televisions and refrigerators that had always been beyond their means. The violence was both random and directed. People tore down traffic lights and also smashed banks and cash machines belonging to the Suharto family. They threw stones at any window that was unbroken, yet concentrated on symbols of wealth. They set fire to buildings but worst hit were those associated with Suharto’s family. Vast crowds demolished car showrooms owned by Suharto’s son Tommy. They burned down the social affairs ministry, run by Suharto’s daughter Tutut, and torched the toll booths her company had built. They ransacked a house owned by Liem Sioe Liong, one of Suharto’s closest friends and Indonesia’s richest man. They burned his fleet of flash cars and slashed his portrait. The chant of ‘Down with the King of Thieves’ rang out.

Alongside the riots, demonstrations of students and workers were continuing. Although virtually unreported, they were large and met with gunfire by the security forces. One victim was 21 year old Teddy Kennedy, the son of a parking attendant, Roy Effendi, who had chosen his boy’s second name in honour of the US president. Teddy had joined one of the demonstrations and was killed by a bullet in the back of his head fired by the security forces. [14]

For the urban poor who made up the majority of the rioters, there were few other ways of expressing their anger. They had no college campus to occupy or student delegation to join, no factory to occupy or strike to organise. They were unemployed or eking out a living in small unorganised sweatshops. Many were provincial migrants, recently uprooted from their villages with no links in the city. Every day they faced harassment and abuse by police and officials. Arifin Hanif, one of the newly unemployed, had been held for two weeks in 1996 and tortured by soldiers. When the riots came, he saw his chance: ‘This is the sort of situation I have been waiting for’. [15]

On their own the riots would have led nowhere. But because they had been sparked by the wider discontent, they quickly stoked up the political crisis facing the ruling elite.

As Jakarta burned, claiming hundreds of lives [16], the military stood by. Many soldiers sympathised with the protests. Troops who were called to secure Indofood’s Jakarta distribution centre, for example, helped the looters. The company’s marketing manager watched the soldiers ask rioters to line up for merchandise and heard them saying, ‘Once you’ve got enough, please go outside and give other people their chance’. [17] Security forces who arrived after people set fire to a branch of Liem’s Bank Central Asia simply warned the rioters not to stand too close to the flames. In many places demonstrators chatted with soldiers, putting flowers in their guns and pleading with them to side with the people.

People who were rioting also began to play an explicitly political role. Outside the National University they urged students occupying the campus to take to the street and actively join the uprising. The students refused, saying they were against violence! On the streets photocopied lists of Suharto’s family’s assets were being sold for the equivalent of 10 US cents. One crowd of rioters rained missiles on a police station and then set fire to it. ‘Police, come out and face us’, they shouted. [18] The Jakarta Post reported someone who was supposed to be part of a ‘mindless mob’ screaming out, ‘The government should realise that the price of fuel must be reduced’. [19]

As the rioting spread across Jakarta, schools and businesses closed. Buses and taxis stopped running, particularly the previously ever present dark blue Citra cabs owned by Suharto’s daughter Tutut. ‘They knew that if they went on the streets they would have been torched,’ said a cab driver. Middle class families put signs outside their houses hailing the martyrs of Trisakti University. Rich Chinese families as well as employees of foreign companies and international organisations fled to the airport. Military trucks began picking up people stranded by the riots and taking them home.

By 15 May, Jakarta was like a deserted battlefield. Few people ventured out. Most businesses were shut and currency trading was halted. Vast areas had been reduced to rubble-in all, the destruction was worth about a billion dollars. More than 5,000 buildings had been destroyed or damaged. At least 500 bank branches and 200 cash points had been trashed. Hero supermarket, the largest chain in Indonesia, lost 25 of its 40 outlets in the capital. Whole factories, including the Unilever factory in the eastern suburbs, were burned down. Meanwhile, protests were intensifying in other parts of the country. In Yogyakarta, students clashed with security forces, threw molotov cocktails and stones at police lines, and burned photographs and effigies of Suharto. Students also took a member of the local parliament hostage. In this city police responded with teargas, rubber bullets and water cannon.

Significantly, in the major industrial centre of Surabaya, where students and workers joined forces, the security forces were passive. Students stormed the radio station RRI and forced their demands to be broadcast while thousands of people kept guard outside. Elsewhere in the city rioters attacked the provincial legislative office. Security forces closed off streets but not a single shot was fired. [20] As a result, yet more activities were organised. The Jakarta Post reported, ‘About 4,000 housewives, female students, factory workers, activists, nuns and prostitutes gathered at the Airlangga University and held a free speech forum where they voiced support for the student movement for reform’. [21] Rioting and student protests erupted in practically every major city across the country.

The reverberations of the protests reached Cairo, where Suharto was meeting other rulers during the G15 Summit of developing nations. He flew back to Indonesia on 15 May, apparently thinking that if he asked a few unpopular cabinet ministers to resign, especially his daughter Tutut and his close friend Mohamad ‘Bob’ Hasan, the protests would end. His parliament seemed loyal enough. A few hours later he had lost much of its support. The House Speaker, Harmoko, one of Suharto’s most trusted allies, turned on him, calling on him to resign ‘for the sake of national unity’. Harmoko’s words were too late to save his house, which was being burned to the ground as he spoke.

Meanwhile, the protests intensified. Thousands of student protesters in the Central Java capital of Semarang, joined by hundreds of workers, took over the state owned radio and forced the station to air their demands for reform. Violent clashes between students and police broke out in Surakarta, Central Java, Bogor, West Java and in Medan, where the students sat down and held a free speech forum as they blocked the traffic. They also sang anti-government songs and posed for photographs with soldiers. [22] In Purwokerto, Central Java, over 3,000 students tried to break through a police barricade and were only driven back by teargas. In Bandung, West Java, nearly 100,000 students from colleges all over the province occupied Gedung Sate, the centre of the provincial administration and the provincial council.

The authorities then seemed to realise that Surabaya was a key battleground. A special reserve force headed by Suharto’s son-in-law Prabowo was deployed to confront the might of the city’s huge workforce and student population. It roared through the city firing on demonstrators, lashing out with rattan canes and wooden clubs. A Guardian journalist described one of many incidents: ‘This time the shooting was in response to angry onlookers throwing stones at a lorry-load of the hated strategic reserve troops over the road. The military driver stopped, turned his vehicle and drove straight across the central reservation and headed straight for the stone throwers’. [23] Later, just after the military had agreed to negotiate with student protesters, the military suddenly opened fire: ‘There had been no provocation. But the green-bereted strategic reserve seemed to have no compunction about turning its guns on those protesting against Indonesia’s aging autocrats.’ As a result of the military’s violence, rioting and looting spread, and 2,000 students marched to the provincial council building. [24]

The country was now visibly at war with itself, with cities encircled by military armoured cars and soldiers guarding government buildings. By 18 May it was clear in the capital that something mighty was happening. Students marched into the main parliamentary building, where members were still sitting, and handed out pro-democracy bandanas to the men and women placed there by Suharto. Many of those who for years had done everything in their power to suppress democracy then donned the symbol of democracy. Outside, students were fraternising with soldiers, encouraging them to support the ordinary people. For 32 years parliament had simply been a temple to Suharto: no debates were ever heard. With the students in occupation it was suddenly at the heart of political change.

By 19 May up to 30,000 students were occupying parliament and the security forces were doing nothing. Buses kept arriving, bringing delegations of students clothed in their college colours. Students climbed onto the roof to unfurl banners. A huge cheer went up when a thousand labour activists arrived to add their voice to the call for change. ‘We want Suharto and Habibie to stand down,’ said Datuk Bagindo, chairman of the official trade union federation, SPSI. ‘Because of the economic crisis caused by Suharto’s administration, workers are facing mass dismissals, lay offs and the worst hardship’. [25]

The students inside parliament were typical of student occupiers the world over. They were at once exhilarated and politicised by their daring and terrified of what might happen to them. A 40 metre long banner hung from the roof read: ‘Return sovereignty to the people. Thirty two years is enough.’ Inside the building the air was heavy with the smell of clove cigarettes. ‘In the library, students shredded and burned documents. Someone smashed the glass door to the presidential washroom. Students made out on the lawn’. [26] There was also the consuming fear of another Tiananmen. ‘They lived from hour one with the paranoia of a crackdown, rumours lumbered through the humid air, and, more than once, word came that soldiers were poised to burst in, wielding death,’ reported Asiaweek. [27] The protest was infecting everyone in the city, even stockbrokers. Around 300 stopped work for 20 minutes at the Jakarta Stock Exchange and chanted, ‘Step down Suharto’.

Still Suharto tried to play for time. He announced a cabinet reshuffle and suggested new elections ‘sometime soon’. Then he said he would not stand in them. But even that was not enough. Harmoko’s call for him to quit was supported by three other former vice-presidents. Then 13 ministers resigned.

For several weeks all the opposition had been preparing for mass demonstrations on 20 May, the 19th anniversary of National Awakening Day which commemorates the birth of Indonesia’s nationalist movement. In town after town, village after village, buses and coaches had been booked to take people to marches. A million people were expected to gather at the national monument square in central Jakarta, not far from where Suharto was hiding.

As the momentous day approached, General Wiranto ordered thousands of troops and tanks into and around the capital. Then, on the eve of the protest, he warned that the military would tolerate no further disturbances and would shoot ‘looters’ (demonstrators) on sight. He had a quiet word with Amien Rais, reminding him of the Tiananmen Square massacre in China on 4 June 1989. As the evening of 19 May began, soldiers cordoned off the square with barbed wire and declared it a forbidden zone. By daylight thousands of troops had sealed off the city with light tanks and armoured personnel carriers. As the sun rose further in the sky on National Awakening Day, busloads of students began arriving at parliament to join other students who had spent the night there. People lined the street to welcome them, chanting, ‘Suharto must go.’ Middle class people turned up with food, cigarettes and water for the students. Expectations were high. Everyone was nervous. Today was showdown time.

But then Amien Rais stepped in. He went on national radio and television to urge the people not to march. He said he was afraid of massacres by the army. This was a reasonable fear, given the military’s track record, and was shared by many. But the truth was that Rais was more afraid of the prospect of a million fired-up people gathering in the city and getting out of control. Unfortunately, most people in Jakarta listened to him as there was no other organisation that could give the lead and mobilise people who had shown they were prepared to risk violence in order to win reforms. And so the momentum was lost and the chance of immediately pushing the revolution to greater heights evaporated. In the capital National Awakening Day turned into a day of respectable people gathering at parliament, including Rais, business people and many professionals, to make one demand only: Suharto must go.

In some places outside Jakarta, Rais’s call for people to stay at home was ignored. In Suharto’s home town of Yogyakarta, for example, up to a quarter of a million people took control of the streets. In Surabaya huge demonstrations by workers and students were violently broken up by troops. By the evening it was clear that Suharto was on his way out. The head of his own ruling party gave him a blunt ultimatum: resign or face impeachment. Even General Wiranto was demanding that he go so that he could be replaced in a ‘constitutional’ and orderly fashion. Any further delays might threaten that possibility. The army chiefs pleaded and begged, promising him that they would defend his life and property to the death. Finally Suharto conceded.

At 9am the next morning, on 21 May, Suharto resigned in a televised broadcast: ‘I am of the view that it is very difficult for me to carry out my governmental duties. I have decided to cease to be President of the Republic of Indonesia effective immediately.’

The dictator had gone! A mass movement had ousted him. Everywhere the people cheered and celebrated their victory. Unfortunately, all power did not go to the people cheering, but to Suharto’s best mate and former vice-president, B.J. Habibie – the man who called his erstwhile mentor SGS (Super Genius Suharto).

One of Habibie’s first acts as president was to order security forces to clear parliament of the remaining student protesters. On 22 May they stormed the building armed with teargas, clubs and machine guns. There was no resistance. It appeared that the ‘moderates’ had won and now people would settle down to see what Habibie could deliver. Pretty soon, however, it became clear that Habibie was incapable of dealing with the many crises he faced. The economy was still in freefall and he was trapped by his unwillingness to attack the Suharto family’s business empire and his fear of the far from pacified populace.

In the weeks after Habibie took office, the rupiah kept falling: by 12 June it had crashed to 14,850 to the dollar, a 20 percent fall in a week. There was also a massive run on the Bank Central Asia and the government was running out of money: the central bank’s reserves were down to around $7 billion. The much needed next tranche of the IMF’s $43 billion bail out due to arrive in July would be a drop in the ocean given the scale of debt and the collapse of industries. Unemployment kept rising and was forecast to reach 15.5 million by the end of the year, about 17 percent of the workforce. Inflation, which had already reached 52 percent by June, was predicted to rise to 80 percent by December.

The enormity of the economic problems was undeniable. Almost everyone agreed that the economy would contract by around 20 percent during this year. In the towns and villages, food supplies were running out and anyway were becoming unaffordable. Even if enough could be imported at the higher costs, disrupted distribution systems once run by ethnic Chinese firms were raising prices further. In addition, economics minister Ginandjar Kartasasmita said in June that government subsidies of basic food goods (including flour, sugar, corn, soya beans and fishmeal) would be completely lifted in October, as required by Indonesia’s agreement with the IMF.

In an attempt to distance himself from the regime that spawned him, Habibie raised the possibility of seizing some of the Suharto family profits and investigating corporate corruption. Not surprisingly, he has so far done little to follow this up. Any investigation would quickly lead back to Habibie himself and many of his ministers-all major stakeholders in companies connected with Suharto. Foreign companies are also reluctant to dig up the dirt, as they are almost exclusively established in Indonesia because of sordid deals with Suharto and his cronies.

The close connection between the state, banks and industry in Indonesia, which had been one reason for the economy’s rapid expansion, was now part of the problem. The state’s control of banking and industry had allowed firms to enter international markets from which they would otherwise have been excluded by international competition, defend themselves against technically more advanced rivals, and survive periods of low profits while entering established markets. The state’s involvement also protected imports through tariffs, provided incentives to exporters, and developed the infrastructure and education needed for the development of a modern economy. [28] In addition, the repression combined with a total absence of welfare provision forced workers to save, aiding high levels of investment.

The financial crisis was caused by the age old capitalist problem of too many goods being produced for demand, increased competition, and falling rates of profit. Left to its own devices, capitalism would allow the weaker capitalists to go under-firms would close, banks would collapse and savings would be wiped out-until the system was ready for another round of expansion. This process began happening so dramatically in Indonesia because for years Suharto’s corrupt state had propped up banks and bailed out companies that would otherwise have collapsed. So Habibie faced a harsh choice: further economic decline or the conditions laid out by the IMF. But these conditions mean restructuring banking and industry, ending tariffs, opening up the economy to Indonesia’s competitors, and stopping subsidies (risking further revolts), none of which appeal to the Indonesian ruling class.

Pressure from the IMF as well as continuing protests at home soon began to force the issue. In June relatives of Habibie, Suharto and General Wiranto were resigning almost daily from positions they had achieved by nepotism. Huge contracts with foreign companies, including Thames Water, were being cancelled or reviewed to stem the accusations of corruption. On 4 June the Jakarta Post editorial read: ‘The fury directed against Suharto, stoked by the almost daily reports uncovering his huge business empire, may run out of control to the degree that people may look to take the law into their own hands.’ It continued: ‘We cannot afford this kind of frenzy because it would literally affect just about every sector in the economy, since it is being discovered that Suharto’s family and cronies are engaged in businesses ranging from satellite communications, power, toll roads and printing to oil and gas, transportation, food, pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals and plantations, to name just a few.’ It might have added that Habibie has his claws in around 80 major companies and corporations.

The resignations did not even begin to touch the economic problems that were increasingly affecting millions of Indonesians through job cuts, falls in real wages, rising prices and food shortages. Industrial workers were living off the equivalent of less than 50 US cents a day, and the average per capita income had fallen in a year from $1,200 to $300. Hunger and homelessness faced millions of people in both the cities and the countryside. According to Rekson Silaban of the SBSI union, there were about 150 million people living below the official poverty line.

Such conditions were fuelling the other major problem facing Habibie – continuing social unrest. It quickly became clear that students and workers, bolstered by their recent success and newly won freedoms, would not suffer in silence to allow Suharto’s best mate to protect the interests of the rich while doing nothing for the poor. Each ‘concession’ granted by Habibie to appease popular anger, such as the release of political prisoners, appeared to generate more activity, not less. After he lifted the ban on opposition parties (excluding socialist or communist organisations), political parties began springing up daily. Crucially, workers were being drawn into struggle as they were forced to defend their livelihoods in the face of closures and cuts, and each time they took action they were still facing the might of the military – a strong reminder that even basic democratic reforms had still not been achieved.

One of the first new parties to be formed, the Indonesian Workers Party (PBI), was organised by labour activists in order to challenge for power in any forthcoming parliamentary elections. Sri Bintang Pamungkas, the day after his early release from prison, announced that he would register his long outlawed organisation, the Indonesian Democratic Union Party (PUDI). Feminists got together to found the Indonesian Women’s Party, declaring their aim was ‘to empower women in the political field’. Even the ruling Golkar split, with new parties peeling off.

In early June thousands of workers demonstrated outside the manpower ministry demanding the legalisation of independent trade unions. Habibie obliged by lifting the ban on such unions. The employer who had made so much from suppressing trade unionism promised that his government would never again use military interference in labour disputes and would respect workers’ rights to strike when fighting for their interests. [29] His words had an immediate effect, even though his promise about the military’s role was quickly broken. Muchtar Pakphahan, who had just been released from prison, registered the SBSI and announced that the union would continue its fight to strengthen workers’ bargaining power. Thousands of workers went on strike in many factories across Surabaya and staged huge and violent protests in the streets. They were demanding up to 50 percent wage increases to keep up with spiralling inflation. Thousands more workers from electronic and machinery factories near Jakarta demonstrated to stop job losses. A demonstration of staff at the national airline, Garuda, demanded cancellation of contracts linked to the Suharto family. And the parliament in Jakarta once again became the focus of student protests, with around 5,000 rallying outside to call for more reforms.

Around the country, people emboldened by the May events organised to express long felt grievances. In Purwokerto in Central Java, for instance, 200 farmers rallied to demand the resignation of the village chief who had embezzled their money, while on a vast area of land owned by Tutut which had been cleared for development in north Jakarta, hundreds of slum dwellers staked their claims, driving signs with their names into plots they believed they were reclaiming for Indonesia’s orang kecil (small people).

By the end of June more workers had mobilised. Thousands from three factories demonstrated outside Surabaya’s local parliament. Around 3,000 workers from the Victory Long Age shoe factory demanded pay rises, menstruation leave and tax relief. Some 1,500 workers from two timber factories demanded the sacking of two bosses and pay supplements. On 25 June 1,000 members of the SBSI union rallied in Jakarta calling on Habibie to resign. Some 7,000 workers at the Tryfountex Indonesia factory in Solo went on strike between 30 June and 4 July to demand higher wages and other fringe benefits. After management threatened mass sackings, workers set up an independent Workers’ Committee for Reform (Komite reformasi Kaum Buruh), which among other things called for their factory to be nationalised. The committee also declared that workers should not confine themselves to immediate economic demands, and invited student leaders to address the workforce.

Another political minefield also confronted Habibie. In occupied East Timor tens of thousands of people attended meetings to demand independence. In Jakarta a large demonstration on 12 June calling for East Timorese independence was broken up by police. This was the first use of violence by the security forces since the May uprising and showed that the state was still the same beast that had terrorised the nation for 32 years, albeit with a new face as its president.

Habibie tried to soften the government’s stance on East Timor, offering a limited degree of autonomy some time in the future. But this just fuelled anger. No doubt the issue of East Timor will cause further violence: the government knows that success for the East Timorese independence forces would encourage secessionist movements elsewhere, including Irian Jaya, Aceh and oil rich East Kalimantan.

All over the country, there were increasing signs of class polarisation, as there had been in the days leading up to 21 May. Banners raised at various protests called for Habibie to go, complained at the lack of reforms, and demanded property to be seized from the rich and returned to the people. Tensions were apparent within the student movement between those who believed the overthrow of Suharto was enough, and those who wanted democracy and major economic reforms introduced immediately. Some students wanted solidarity with workers; others rejected such solidarity. Workers were striking for wage increases and to build their own unions, and were being politicised by their constant confrontations with the military. Sections of the middle and ruling classes were meanwhile mobilising to show their support of Habibie and to call for calm. The country was in revolutionary turmoil, but there was no revolutionary leadership.

The appointment of B.J. Habibie in place of Suharto seemed to be the perfect interim solution for the sections of the ruling class that had wanted the least change possible to diffuse the protests. He was a creature of Suharto-a senior government minister since 1978 and intimately linked with Suharto and his cronies of old, including timber king ‘Bob’ Hasan, and Suharto’s son-in-law Prabowo, leader of the most ruthless element in the army. Habibie was best known for the ludicrous money guzzling aircraft industry he established to produce Indonesia’s own aeroplane, the useless N-250. Money was diverted from the government’s reafforestation fund to bail out the company, and Merpati Airlines and the military were forced to buy Habibie’s substandard products. He also has extensive interests in 80 companies linked to government projects, state owned and military run enterprises, and affiliated banks. This is spearheaded by the $60 million Timsco Group, run by his youngest brother, which has its hand in chemicals, construction, real estate, transport, communication and joint ventures with the US telecommunications giant AT&T. Military leaders backed Habibie’s appointment as they felt he offered the best hope of restoring order and protecting the military’s economic interests. On top of the enterprises it seized after independence, the military has established companies and extended its control over state owned corporations such as Pertamina, the oil giant; Bulog, the state food distribution network; and Berdikari, the official trading group.

The temporary installation of Habibie also suited liberal opposition leaders such as Megawati and Amien Rais, who did not want the uprising to get out of control and needed time to prepare for what they hope will be peaceful elections. Megawati, once the great hope of liberal democrats, has proved cowardly and ineffectual. Until the killings at Trisakti, she said nothing. Then she appealed for calm. Soon after Suharto was toppled, she made only her second high profile speech to urge the nation to ‘show compassion and stop battering fallen president Suharto’. A member of the Indonesian elite, she has been paralysed by her terror of the masses. She has repeatedly declared her support for the existing constitution which, among other things, entrenches the army as the dominant political force. She is a fan of Western capitalism and has long been closely associated with those demanding a rapid transition to a free market policy based on private capital and competition.

The main beneficiary of the May uprising was Amien Rais, chairman of the vast Muslim movement Muhammadiyah. A US-trained academic, he won considerable support among students during the protests and came across as a decent liberal. The truth about him is less pleasant. In 1988, for example, the military encouraged him to condemn ethnic Chinese as traitors who were to blame for unrest, thus allowing pro-government Islamic leaders to cheer him on and call for all good Muslims to support Suharto. He was also a leading figure in the powerful Muslim Intellectual Association (ICMI), established in 1990 by Habibie with the backing of Suharto. ICMI is a focus for non-Chinese or pribumi businessmen who resent the influence of wealthy ethnic Chinese families.

Rais’s class allegiance was fully exposed on 19 May when he called off the mass rallies scheduled for National Awakening Day. Like Megawati, he represents sections of the ruling class who missed out on the gravy train, as well as intellectuals and members of the middle classes who want liberal democracy but are nervous of mass struggles. Both he and Megawati were among the first to support the IMF’s intervention and conditions, and both have the support of the international ruling classes, who fear further damage to some of the biggest companies in the world-BP, Shell, Rio Tinto, General Electric, Siemens, NEC, Hyundia and BHP-which have joint ventures with members of the Suharto elite. Since 21 May, Rais has bent over backwards to prove his credentials to his Western admirers. He backed Habibie’s appointment, stressing their personal friendship. He said he did not think the new president would be Suharto’s puppet. ‘If somebody is intelligent enough to make an aircraft, I hope he is intelligent enough not to be a puppet leader,’ he told journalists. [30] Soon after, in early June, he told a mass student rally that debates on the legitimacy of Habibie’s appointment ‘should stop’. Everyone should calm down and wait for elections, whatever the delays.

Megawati and Rais are a barrier to further reforms that are so deperately needed to ease the suffering of the masses. Not only have they failed to mobilise people who were only too ready to fight, but they have also poured cold water on those who had joined the struggle. Rais was honest about his fears as far back as February 1998, when he told an ABC interviewer, ‘Mobilising people is easy, but controlling them is difficult.’

The perceived wisdom expounded by Megawati and Rais, and accepted by many in the reform movement, is that all Indonesia’s problems are due to ‘crony capitalism’. Once the cronies are removed, so the argument goes, then capitalism in Indonesia will once again flourish. The truth is that no section of the Indonesian bourgeoisie, however liberal sounding, will be able to carry out the measures required to even begin to tackle the inequalities, poverty and economic crisis in Indonesia. For that to happen, some of the enormous material resources would have to be taken from the elite and the multinationals and given back to the people, and major political and social reforms would need to be introduced. Those leading the opposition have no desire to do this, and even if they did, the full might of the army would be mobilised to protect not only their political role in the country, but also their material wealth.

As has been demonstrated above, the key political force for change in the run up to May was the students. Half the Indonesian population, around 100 million people, are aged under 20. They do not remember 1965, have been angered by the lack of free speech and repression, and are fearful of the lack of opportunities they face as the economy crumbles. Although they were crucial to the events leading up to Suharto’s overthrow as they sparked much wider protests, students alone cannot and will not change Indonesian society more radically. Most come from relatively privileged backgrounds and their demands are limited. More importantly, students alone, however radical, do not have the power to overthrow the ruling class.

However, students have shown Indonesians that mass action can win, and have raised expectations about justice and democracy in the country. To make even more progress, especially on the economic front, organised labour needs to be mobilised and politicised. If they use mass strikes and factory occupations to voice political as well as economic demands, then the ruling class would come under intense pressure. In the process of such collective action, a political movement independent of liberals such as Megawati and Amien Rais could be developed. Key to that process is the working class and the left.

During the protests that led up to 21 May, the workers were relatively passive. The main reason was the shadow of unemployment which hung over every factory. As the economy disintegrated, millions of workers were laid off – thrown into instant poverty in sprawling slums where they had few, if any, family ties. According to the Indonesian Writers’ Syndicate, more than 16 million industrial workers were laid off in the six months up to May. Those still in work were desperate for the wage packet that would stave off hunger.

The other reason was the absence or weakness of trade union and political leadership. Independent trade unionism had only begun to grow in the past few years so its roots were weak and its presence uneven across the country. Moreover, its leaders and activists still faced the most brutal repression right up to the May uprising. When Suharto fell, most of the leaders of independent trade unions and hundreds of union activists were in prison or had been killed.

The weakness of the left was again a legacy of the years of repression, but also of the disastrous experience of the PKI in the 1960s. No independent revolutionary socialist organisation exists, even in embryo form. The most radical organisation is the People’s Democratic Party (PRD). Despite being condemned by the government as ‘Communist’, it is in fact a radical reformist organisation. Its main demand has been for a ‘people’s coalition government’ rather than a socialist revolution, although some of its members are socialists. It was formed in April 1996 and almost immediately the PRD and its affiliated organisations were banned by Suharto after the protest outside the PDI office.30 Most of the leaders were arrested, including PRD chairman Budiman Sujatmiko and Dita Sari, head of its affiliated independent trade union PPBI.

The PRD worked in alliance with Megawati’s Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI) and recently focused its efforts on the urban poor rather than organised workers in an effort to promote ‘popular radicalism’. Nevertheless, the PRD demands self determination for East Timor and is undoubtedly militant – one of its slogans is ‘Look for the fire, fan the fire’ – and has organised workers to take industrial action. In early 1998 the PRD was extremely small given the scale of events, having only a few hundred members and a few thousand supporters. Most of its core activists are students and former students. But its calls for the overthrow of Suharto and its pro-democracy slogans appear to have gained it much support.

In the current climate there are huge opportunities for the left to prosper. One reason is that the situation remains incredibly volatile. Firstly, the effects of globalisation mean that countries such as Indonesia are vulnerable to currency speculation, the flight of capital and intense competition from neighbouring countries. Combine this with the organic crisis of Indonesian capitalism and the deepening regional and world economic crisis and it is clear that there is every chance that Indonesia will continue to slide deeper and deeper into recession, with devastating effects for the mass of Indonesians. On the political front, the lack of effective democratic and legal institutions means that the authorities have few tools to channel the spirit of reform. Similarly, the absence of established social democratic or Stalinist parties and the weakness of the trade union bureaucracy to moderate and mediate struggle also makes the situation potentially explosive. In such a climate, the current leaders of the reform movement may be quickly exposed.

On 1 June, for example, dozens of red and white banners appeared on the capital’s main streets with the names of the best known opposition leaders. But there were also slogans that would terrify those same leaders: ‘People are starving! Take back people’s money.’ If the economic situation continues to worsen, the contradiction between the aims of the liberal leadership and the needs of the people will become ever clearer. If a socialist voice could be organised and heard, it would quickly gain support.