Main NI Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From The Militant, Vol. X No. 34, 24 August 1946, p. 6.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

Normally, the price of commodities reflects the laborvalue that is in them. This point was dealt with in last week’s installment. Wages, the price of labor-power, are controlled by the same law of labor-value, through the same process of competition. In this case, it is competition in the labor market.

The sellers, the workers, try to get the best wage they can, while the buyers, the employers, try to buy cheaply. The workers must sell their labor power somehow, for they cannot live without a job. No one worker can keep his wage standard high, because he knows the employer will hire some other worker at a lower wage, and leave him unemployed.

The employer offers the lowest wage at which he can hire workers. It turns out there is a point below which workers will not go. In the long run, workers will not take jobs at wages below the cost of living, because they can’t. They might as well starve unemployed as starve on the job. Moreover, at that point the workers can organize most strongly to strike for higher wages. No group of the workers within the union will consent to settle a strike and go back to work for less than a living wage.

So the level of wages that comes from bargaining in the labor market is determined indirectly by the cost of living. The cost of living is another way of saying the cost of production of the worker’s labor power. In order to work the worker must get goods enough to live, to keep him healthy and strong enough to work, and to support his family so there will be other workers in the future.

Wages obey the law of labor value. The normal wage for a day’s work equals the amount of labor required to produce the worker for the day’s work.

How much labor to support a worker for a day’s work? He and his family eat a certain number of pounds of food, which took a certain amount of labor to produce. They wear out a certain fraction of their clothes, use up a certain fraction of housing, burn up some fuel for heating and so on, all of which took labor to produce. At a rough estimate, the goods used up by an American worker and his family in living a day probably took less than two hours total labor in production. He works eight hours (or more) and gets back the output of two hours labor.

As farming becomes more efficient, a worker on a farm produces more pounds of food by a day’s labor. Thus each pound of food contains less labor-value. But so many pounds of food will nourish a worker and his family just the same. A similar increase in efficiency takes place in clothing, housing, everything. Productivity goes up. But wages do not go up with productivity. Through the law of labor value wages are controlled by the amount the worker needs to live on, not by what the worker produces.

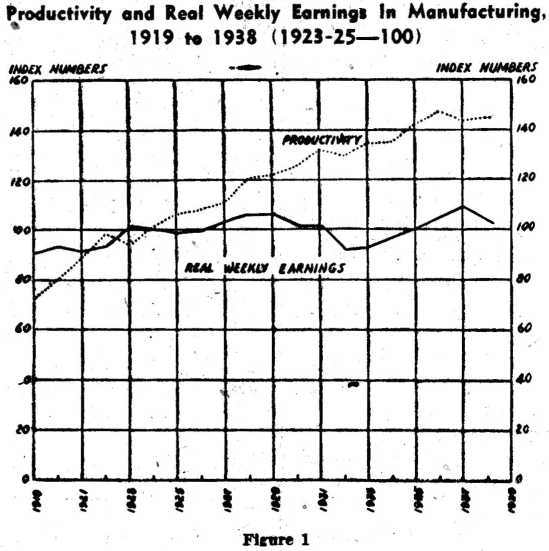

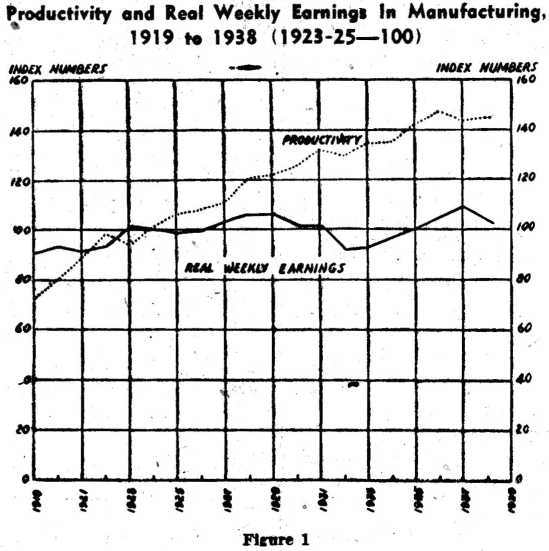

We see from statistics pictured in the above chart that the average worker’s output in goods doubled between 1919 and 1938. But real wages, wages measured in goods, did not go up. They stayed very close to an even level through the whole time. The law of labor-value shows the reason why.

|

The goods a worker produces in one day contain the total value of his one day’s labor. We’ll call it 8 hours labor time. That’s what he produces, measured in laborvalue. His wages buy enough goods to live on for a day. The labor it took to produce the goods he can buy is the amount he gets, measured in labor value. We’ll estimate 2 hours labor in what he gets. The difference, the output of 6 hours labor stays in the hands of the employer. This difference between the labor-value the worker produces and the labor-value the worker gets is called “surplus value” in Marxist economics.

The surplus value is the employer’s margin. Increased efficiency in output only increases the surplus value.

The law of wages, like the law of prices, works out indirectly, through the bargaining process between employers and workers. The actual wage settled on depends, as Marx said, on “The respective powers of the combatants” (Value, Price and Profit). The Real Wage line in the above chart shows how wages dropped in 1932, as unemployment weakened the bargaining power of the workers. Wages rose from 1934 through 1937, as the strike waves, and the CIO organization drive in the mass industries increased tabor’s power to bargain.

The level of wages settles at the point where the workers must say, or have organized strongly enough to say, “Below this we will not go.” That point is governed first of all by the amount of goods they need, but also, as Marx said, by their “traditional standard of life,” and by the strength of their working class organizations.

Next Week: What Becomes of Surplus Value

Main Militant Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 26 June 2021