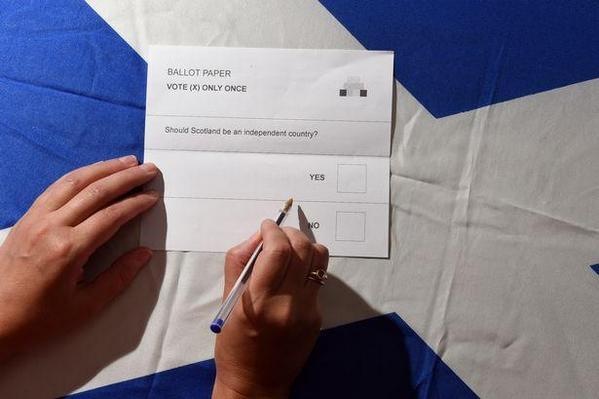

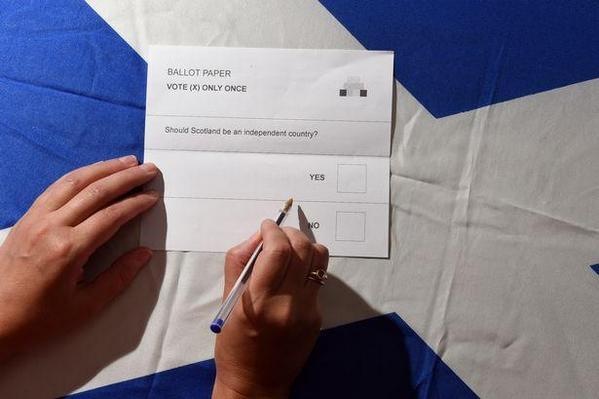

Photo: Ninlan Reid, flickr

Neil Davidson Archive | ETOL Main Page

Scotland: Social Movement & Crisis

Published by rs21, 16 November 2014.

Copied with thanks from the rs21 Website

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

Part one of a major five-part analysis of Scottish politics after the referendum, by Scottish historian and activist Neil Davidson. The Scottish independence referendum was one of the most important political events of recent years. Faced with the possible break-up of the UK, the British ruling class panicked in a way we’ve not seen for decades. The No victory has done nothing to bolster the mainstream parties which supported the union – the resignation of Johann Lamont as leader of Scottish Labour has only highlighted the decline of the Labour Party in Scotland. After almost all of the radical left campaigned for a Yes vote, discussions continue about how the left should organise – the Radical Independence Campaign conference, involving 3,000 delegates in Glasgow on Saturday 22 November, will be an important part of that process. One sign of the referendum’s impact has been the levels of recruitment to political parties since. Figures from 12 November show that SNP membership has more than trebled, from 25,000 to over 84,000; the Scottish Greens have done the same, going from 2,000 to 7,500 members; and Scottish Socialist Party membership has more than doubled from 1,500 to 3,500. Meanwhile the Scottish Labour Party has grown by only a fraction, from 12,500 to 13,500 – fewer recruits than the SSP. Over the next five days we’ll be publishing a major analysis of these events, Scotland: the Social Movement for Independence and the Crisis of the British State, written by Neil Davidson in the two weeks after the vote. With the fifth article we’ll include a printable version of all five parts, for those who prefer to read long documents in printed form. |

Photo: Ninlan Reid, flickr |

If, in 2011, you had asked members of the radical left to identify a sequence of events that might lead to a crisis of the British state, most would have probably nominated a combination and escalation of the struggles then current: public sector strikes in defence of services and pay, riots in communities subject to police violence, and student demonstrations against tuition fees, perhaps set against the backdrop of opposition to yet another imperialist war in the Middle East. A referendum on Scottish independence is unlikely to have featured high on the list. Yet within three years such a referendum had momentarily rendered the actual end of the British state a realistic prospect and, for two weeks in September, the campaign for a Yes vote had reduced the British ruling class to a panic unparalleled since the early stages of the Miner’s Strike of 1984–5 and, in terms of public visibility, since the industrial struggles of the early 1970s.

Obviously this was contrary to the pieties of the Approved Left Strategies Playbook. According to conventional wisdom, a referendum would at best only encourage constitutional illusions, at worst lead to national divisions among the British working class. Typical exponents of this type of thinking were representatives of the Red Paper Collective [1], a reformist think-tank uniting trade union officials and Labour-supporting academics, who asked for “a better use of the labour movement’s time and resources than signing up to be foot-soldiers in one or other of the bourgeois campaigns currently vying for attention.” The suggestion that abstention was the appropriate response is rather disingenuous, since everyone associated with this group opposed Scottish independence and supported the continuing unity of the British state. [2] But even leaving that aside, the approach was in any case totally misguided.

In a capitalist society, all politics is by definition “bourgeois” unless working-class interests are forced onto the agendas which would otherwise exclude them. Some areas of political life are obviously more susceptible to working-class intervention than others, and some will always have greater priority, but none can be dismissed as entirely irrelevant. As the late Daniel Bensaïd [3] wrote, in his attempt to capture the essence of Leninism:

If one of the outlets is blocked with particular care, then the contagion will find another, sometimes the most unexpected. That is why we cannot know which spark will ignite the fire.

In this conception, which I endorse, the watchword is: “‘Be ready!’ Ready for the improbable, for the unexpected, for what happens.” Improbable as it may at first appear, the Scottish independence referendum became one of Bensaïd’s “outlets”.

Anyone who relied on commentaries by the Labour-supporting metropolitan liberal-left to understand events in Scotland might well be puzzled by this conclusion. For, whether out of conscious dishonesty or simply catastrophic levels of ignorance, the inhabitants of this milieu chose to portray the Yes campaign as an essentially ethnic movement. [4]. John McTernan, a former Labour Special Adviser, wrote on the day of the referendum:

Populism is sweeping Europe, and the UK is not immune. The SNP surge is part of this phenomenon. The characteristics are putting the nation and its needs and aspirations above other calls on solidarity.

I pause only to draw attention to the fact that this call for solidarity was being issued in the pages of the Daily Mail, before noting McTernan’s claim that there is a “clear populism of the Centre-Right – UKIP and the SNP in the UK.” Phillip Stephens of the Financial Times wrote that Salmond “has reawakened the allegiance of the tribe”, before also comparing the SNP with the racist xenophobes of UKIP: “Mr Salmond is to Scotland what Nigel Farage, the leader of the UK Independence party, is to England.”. The Observer’s Will Hutton [5] saw Scottish independence as heralding the Decline of Western Civilization:

If Britain can’t find a way of sticking together, it is the death of the liberal enlightenment before the atavistic forces of nationalism and ethnicity – a dark omen for the 21st century. Britain will cease as an idea. We will all be diminished.

Scottish novelist C.J. Sansom [6] at least allowed that the intentions of Yes supporters were commendable:

Some, certainly, will be thinking about voting yes on Thursday, not from nationalism, but in the hope of social change. Yet they will not get it, because, like it or not, they are voting for a nationalist outcome… And the SNP, who will be victors and negotiators of Scotland’s future, are not socialist, but classic populists who over the years have swithered around the political spectrum to gain votes for nationalism.

But those who do not wish to talk about British nationalism should also remain silent about Scottish nationalism. Michael Keating [7] points out, in a comment that might have been written with these commentators in mind: “Some of those who condemn minority nationalism as necessarily backward frame this as a condemnation of all nationalism, ignoring the implicit nationalism underlying their own position and confusing their own Metropolitan chauvinism with a cosmopolitan outlook.”

In fact, for most Yes campaigners the movement was not primarily about supporting the SNP, but nor was it even about Scottish nationalism in a wider sense. “For me”, writes Billy Bragg [8], “the most frustrating aspect of the debate on Scottish independence has been the failure of the English left to recognise that there is more than one kind of nationalism.” Bragg’s support was welcome, particularly in the pages of the Guardian, which in most respects played an abysmal role during the referendum campaign, but these comments confuse the issue. As a political ideology, nationalism – any nationalism, relatively progressive or absolutely reactionary – involves two inescapable principles: that the national group should have its own state, regardless of the social consequences; and that what unites the national group is more significant than what divides it, above all the class divide. Neither of these principles was dominant in the Yes campaign. One right-wing, but relatively level-headed No supporter [9] observed:

Those out canvassing don’t report encountering more blood-and-soil types than before. Instead, they say that what is driving people is a variant of the anti-politics mood that is roiling politics across the UK.

More precisely, Yes campaigners saw establishing a Scottish state, not as an eternal goal to be pursued in all circumstances, but as one which offered better opportunities for equality and social justice in our current condition of neoliberal austerity – in other words as a way of conducting the class struggle, not denying its existence. Writing in New Left Review in 1977, Tom Nairn [10] said:

The fact is that neo-nationalism has become the gravedigger of the old state in Britain, and as such the principal factor making for a political revolution of some sort in England as well as the small countries. Yet because this process assumes an unexpected form, many on the metropolitan left solemnly write it down as a betrayal of the revolution… The essential unity of the UK must be maintained till the working classes of all Britain are ready.

Nairn is often regarded as simply being premature in his assessment, and his point about the “unexpected form” of the threat to the British state is certainly relevant; but nevertheless “neo-nationalism” is not the gravedigger, for reasons well expressed by the Irish writer Fintan O’Toole [11]:

The Scottish referendum is…a symptom of a much broader loss of faith in the ability of existing institutions of governance to protect people against unaccountable power. This why the campaign is not particularly nationalistic… The demand for independence just happens, for historical reasons, to be the form in which Scots are expressing a need that is felt around the developed world, the urgent necessity of a new politics of democratic accountability.

Independence has therefore become the demand of socialists, environmentalists and feminists. The sections of the Scottish radical left who actively supported a Yes vote – the overwhelming majority, bar some fossilised sectarians – were therefore right to throw themselves into the campaign and, in doing so, took part in one of the greatest explosions of working class self-activity and political creativity in Scottish history, far greater in depth and breadth than those around the Make Poverty History/G8 Alternatives mobilisations in 2005, the Stop the War Coalition in 2002–3 or even the Anti-Poll Tax campaign in 1987–90. The level of participation and relative closeness of the outcome, for which the left can claim much of the credit, are two measure of this. Yet when the campaign began, early in 2012, there was no indication that it would take this form.

From 2000 onwards the SNP included in its electoral manifestos a commitment to carry out a referendum on independence, if it achieved a majority in the Scottish Parliament. Once that majority was achieved in May 2011 a referendum of some sort was inevitable. Under the Scotland Act (1998) all constitutional issues relating to the 1707 Treaty of Union between England and Scotland are reserved to Westminster. The question was therefore whether the referendum would be an “unofficial” one conducted by the Scottish Government (similar to one scheduled to be held in Catalonia on 9 November), or one in which the process was legitimated and the result consequently recognised by the UK government. Prime Minister and Conservative leader David Cameron took the initiative on 8 January 2012 by announcing that Westminster would legislate for a referendum to be held, but there were conditions; above all, there would only be one question. In other words, there would not be an option to vote for Maximum Devolution, or “devo max”, as it has come to be known.

Devo max was the option overwhelmingly supported by most Scots, perhaps as many as 71%, at this point. Although there are different conceptions of what exactly this might involve, the most complete version would have left the Scottish Parliament in control of all state functions (including taxation) with the exception of those controlled by the Foreign Office, the Ministry of Defence and the Bank of England. The bulk of the SNP leadership recognised that there was not – or at any rate, not yet – a majority for independence. Devo max was therefore what the SNP hoped to achieve – and more importantly, what they thought they could achieve – in the short-to medium-term. Scottish First Minister and SNP leader Alex Salmond would therefore have preferred devo max to be included on the ballot paper, since he would have been able to claim victory if the result was either independence (unlikely) or devo max (most probable).

Cameron refused to play ball. His reason for insisting on a stark alternative between the status quo and independence was simple enough: he wanted to decisively defeat the latter, if not for all time, then at least for the foreseeable future, without allowing voters an opt-out. The risks involved seemed small – he was as familiar with polls showing minority support for independence as Salmond, after all. We should not imagine, however, that Cameron was therefore opposed to devo max. On the contrary, in a speech in Edinburgh on 16 February he offered further measures of devolution if voters rejected independence. For tactical reasons Salmond affected to believe this was a ruse to lull the Scots into voting for the status quo, after which the promise would be quietly forgotten; but while there are historical precedents for doubting the veracity of Conservative promises, in this case I believe they were perfectly genuine, for reasons which, as we shall see, have now acquired urgent political importance. Cameron was however prepared to pay a high price for a one-question referendum. He eventually conceded to the SNP leader his demands for the enfranchisement of 16- and 17 year olds, the right to decide on the date and the nature of the question, thus enabling Salmond to frame it as a positive (unlike, “should Scotland remain part of the UK?”, for example) and campaign for an upbeat Yes rather than a recalcitrant No. These were all confirmed by the Edinburgh Agreement, signed by Cameron and Salmond for their respective governments, at St Andrews House on 15 October 2012.

Even though devo max was absent from the ballot paper, the version of independence promoted by the SNP closely resembled it, retaining as it did the monarchy, membership of NATO and the pound through a currency union with the Rest of the UK (RUK). The intention here was clearly to make the prospect of independence as palatable as possible to the unconvinced through the continued presence of these institutions, so that independence involved the fewest changes to the established order compatible with actual secession. However, as became clear during the campaign, most Scots voting for Yes wanted their country to be as different from the contemporary UK as possible, so this approach hampered the official Yes campaign from the start. Moreover, the issue of the currency placed a weapon in the hands of the No campaign which they were to use remorselessly until the very end.

The official Yes campaign, “Yes Scotland” was launched on 25 May, and was unsurprisingly dominated by the SNP with, in supporting roles, the Scottish Green Party and the Scottish Socialist Party. Its rival, “Better Together” followed on 25 June, uniting the Scottish Tories, the Scottish Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Labour Party – the latter providing both the campaign’s front man in the shape of former Chancellor Alasdair Darling and the bulk of its activists on the ground. Early in the campaign some Labour activists attempted to nullify their embarrassment at being in league with the Conservative enemy by pretending that the entire business was simply a tiresome distraction involving equivalent cross-class alliances on both sides. Pauline Bryan [12] of Labour Campaign for Socialism and the Red Paper Collective wrote:

In Scotland we can see that the SNP and particularly the Yes campaign are a broad alliance across the political spectrum, and the referendum has resulted in the better together campaign which has the support of the Tories, Lib Dems and Scottish Labour. It takes the politics out of politics.

This is simply an evasion. The most obvious difference between the two sides can be seen if we list those forces which stood behind the No campaign: the supposedly neutral institutions of the British state, in particular the Treasury and the BBC; most British capitalists; UKIP and the British National Party; the Orange Order; the entire press with the sole exception of the Glasgow Sunday Herald (and the more right-wing – i.e. the Express and the Mail – they were, the more rabidly Unionist they also tended to be); the President of the USA and his likely Democrat successor; the Commission of the EU; and the rulers of all nation-states with insurgent minority national movements. In short, behind the three Unionist parties stood the representatives and spokespersons of the British and international capitalist class, supporters of the current imperial ordering of the world system, and reactionaries and fascists of every description. Finding oneself in this company, anyone on the left might reasonably ask themselves whether it was conceivable that these people and organisations could all have misunderstood their own class interests, which, one assumes, do not include preserving the unity of the British labour movement.

Tomorrow – Part 2: The Yes Campaign as a Social Movement

[1] Red Paper Collective, The Question Isn’t Yes or No, Scottish Left Review 73 (November/December 2012), [2].

[2] Beyond politics, the prospect of an end to the British state seemed to infuse some No voters – particularly activists on the Unionist left – with a sense of existential dread and ontological uncertainty.

[3] Daniel Bensaïd, Leaps! Leaps! Leaps!, International Socialism, second series, 95 (Summer 2002), p. 77; Lenin Reloaded: Towards a Politics of Truth, edited by Sebastian Budgen, Stathis Kouvelakis and Slavoj Žižek (Durham, North Carolina: University of North Carolina, 2007), p. 153.

[4] John McTernan, Political success? Just climb onto your soapbox ..., Scottish Daily Mail (19 September 2014); Phillip Stephens, The World is Saying No to Scottish Separation, Financial Times (12 September 2014). For a definitive refutation of these idiotic comparisons, by two founders of the Radical Independence Campaign, see James Foley and Pete Ramand, Yes: the Radical Case for Scottish Independence (London: Pluto Press, 2014), pp. 38–40.

[5] Will Hutton, We have 10 Days to Find a Settlement to Save the Union, The Observer (7 September 2014).

[6] C.J. Sansom, Saying No will Arrest the Rise of Populist Nationalism, The Guardian (15 September 2014). See also Historical Note, in Dominion (London: Mantle, 2012), pp. 590–592 where Sampson actually compares the SNP to the inter-war fascist parties.

[7] Michael Keating, Nations against the State: the New Politics of Nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia and Scotland (Second edition, Houndmills: Palgrave, 2001), p. 24.

[8] Billy Bragg, Voting Nationalist in Scotland isn’t an Act of Class Betrayal, The Guardian (17 September 2014).

[9] James Forsyth, The Unionists Have Been Too Afraid to Make a Proper Case, The Spectator (13 September 2014).

[10] Tom Nairn, The Twilight of the British State, New Left Review I/101–2 (February–April 1977), pp. 59–60; The Break-Up of Britain: Crisis and Neo-nationalism (Second edition, London: Verso, 1981), pp. 89–90.

[11] Fintan O’Toole, Forget Braveheart, Kilts and Tribal Nationalism, This is about Democracy, The Guardian (13 September 2014).

[12] Pauline Bryan, Powers for Political Change, Class, Nation and Socialism: the Red Paper on Scotland 2014, edited by Pauline Bryan and Tommy Kane (Glasgow: Glasgow Caledonian University Archives, 2013), p. 193.

Neil Davidson Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 15 May 2020