South Asia

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism (1st series), No.69, May 1974, pp.7-12.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

HALF THE world’s population lives in south, east and south-east Asia, and lives in the main in extreme poverty. It was thought in the 1940s that the pillage of western imperialism could be ended by removing colonialism, enabling the countries of Asia to lay hands on their own resources and begin to build industry and develop agriculture. The conquest of poverty would then be in sight. An identical optimism infected both those who believed this transformation could be effected by private capitalism and those who saw only state capitalism as the means. In general some combination of the two was envisaged, with state industries and planning providing the driving force for the whole society.

In the 1950s, the Korean War boom in commodities, the sustained arms expenditure of the Cold War and the competition between East and West in aid buoyed along these hopes. Large public sectors, five-year plans, the rapid development of heavy industry, land reforms, even a modicum of welfare measures, provided a coherent reformist programme for development independent of imperialism.

The hopes were illusory. The increased instability of world capitalism in the 1960s has, stage by stage, revealed that very little has changed in the relationship of the metropolitan and backward countries, despite the achievements in the period since independence. Bit by bit, the reformist strategy has been knocked away.

Neither private nor state capitalism is able to prevent an increasing gap in income between backward and advanced, to prevent unemployment rising, to assure a secure and rising food supply, to guarantee the complete security of national frontiers against foreign aggression or the regimes against overthrow.

Asia is the most victimised segment of the world economy. When there are general difficulties in the world system, they are seen here in their most savage form-in terms of the dead. The present world ‘recession’ is a disastrous slump here. Its political effects are already apparent in the increasing instability of most Asian countries – student riots against the authoritarian regime in South Korea, permanent martial law in the Philippines, the collapse of the Thai regime, riots against Japanese imperialism in Indonesia.

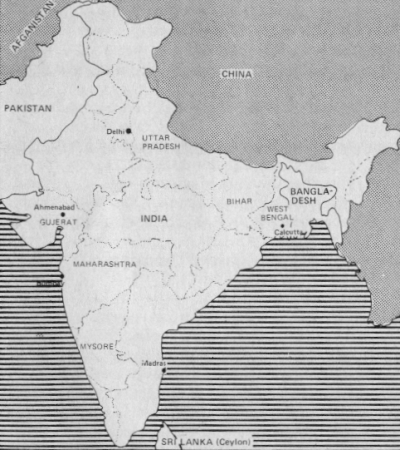

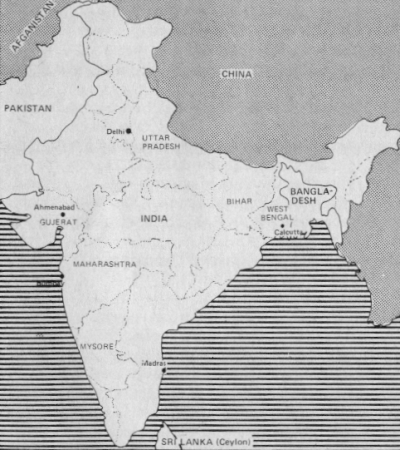

South Asia (the Indian subcontinent and Ceylon) is possibly the largest concentration of poor people in the world, and is even more victimised than its Asian neighbours. None of the countries concerned has attained a real momentum of economic growth. The people are too poor to support the scale of capital accumulation required, the imperialist powers will neither meet the cost nor even provide the markets for the goods of these countries, and each ruling class is now more obsessed with the leeching of its own people than development.

|

|

South Asia |

|---|

Without economic growth, agriculture is unable to meet the food needs of a rising population, nor industry the need for jobs. Defence against its own people becomes the sole means for a ruling class to preserve its privileges.

But this makes the economic problems even worse. The technology of modern armaments demands a massive consumption of scarce resources and heavy imports of sophisticated weapons – which have to be paid for out of exporting commodities in poor demand on the world market or by taking on more foreign debts and conditions. Present arms expenditure in backward countries is roughly equal each year to all the aid transfers from advanced to backward countries in the second United Nations Development Decade. Arms imports are increasing in backward countries by 9 per cent per year, 90 per cent of them from the US, Russia, Britain and France.

The real crisis, however, comes in food. The vulnerability of Asia to famine has steadily grown. New agricultural techniques – the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ – increased output where capital was abundant, but it hardly changed the basic situation. Now its effects are limited by the central lack, capital. 90 per cent of the world’s rice is produced in Asia, and monsoon failures tend to affect all Asian rice growers together, so there is little offsetting of harvest failures in one country by bumper crops in another. When scarcity is worst, prices of the little rice that is traded soar – Thai rice export prices, on average about 130 dollars per ton, rose to 200 dollars in February 1973 and later to 500 dollars. Crop failures in 1972 were not made up in 1973, nor did prices come down.

The failure of the Russian wheat harvest and a poor Indian crop in 1972 set off an escalation of wheat prices that has continued ever since, and been made even worse by world inflation in other commodities. The Russians succeeded in getting a large part of US stocks at a relatively low price, but this led to a change in US government support policy – and the US supplies 60 per cent of the world’s traded wheat and most of the animal fodder – which drained US stocks dramatically. The resulting world scarcity further pushed up prices – the Chicago world price increased from 80 dollars per ton to 600 dollars per ton in 1972-3.

Any Asian need for wheat to feed people has to compete with British and Japanese need to buy animal fodder, and only the wheat growers benefit. Stocks round the world at an all-time low – they are a third now of what they were four years ago, meanwhile the world’s population has increased by 300 million – and very high prices makes it impossible for Asian countries to ward off famine if the weather fails.

The capacity of agriculture to feed people is rendered more difficult still by other elements in the present inflation. Fertiliser prices have soared – for example, urea, priced at 40 dollars per ton in 1971, is now 260 dollars. Because of high wheat prices, European and US farmers are buying up world traded fertilisers, even though their land is already overfertilised and returns are small from any additional application, leaving Asia with a fertiliser shortage even though a ton applied there produces an increase of eight tons of grain. Again, the fattening of European and American cattle is in competition with the starvation of the people of Asia.

The increase in oil prices only makes for less fertiliser and higher prices. It also directly affects agriculture production by restricting the transport of crops, irrigation, tube well and drainage pumps, heat and light. It makes the continued development of industry at an acceptable pace impossible. The balance of payments difficulties of the advanced countries prompts them to cut aid flows, making it even more difficult for the backward to purchase oil, foodstuffs or industrial equipment.

The least regrettable casualty of this crisis is reformism; But the collapse of optimism does not mean an end to nationalisation. Indeed, every government in south Asia nationalises now as a tactic of despair rather than as a means to direct and plan development. Without a political change, nationalisation is merely another tactic of ruling-class survival, abandoning a segment of the private capitalist class to preserve the state. The rich peasants are alone in profiting. The local and world market laws of value grind all the rest between them.

Nationalisation goes with increasing press censorship, attempts to curb or destroy the unions, a ban on strikes, the increasing use of the police and military to destroy all opposition. The populist rhetoric of the regimes is no more than whistling in the gale. Alongside the talk of socialism, the members of the ruling class take the easy way of grabbing what they can and salting it away abroad.

The collapse of reformism affects even more the so-called revolutionary parties. Most of the Communist Parties were not revolutionary at all. They were ginger groups in the ruling class, funnelling middle-class demands for more jobs in the government service, and using worker grievances as a basis for parliamentary power. They were all essentially nationalist. Such politics were possible when the ruling class knew where it was going. But now its own survival depends upon squeezing both middle and working classes. The Communist Parties have to choose, and in general they have instinctively chosen to side with the ruling class. In the process, fragments have broken away from the parties, but usually without any politics other than a rejection of parliament and embrace of individual violence. Nationalism – and a state capitalist reformism – remain the same.

As a result, the amazing militancy and anger of organised workers remains unconnected to the demand for workers’ power, the struggle to conquer the state. Yet it is impossible to see any nationalist solutions to the current crisis. The crisis is an international one, and there is no force capable of solving it other than the working class. Yet still most young revolutionaries remain trapped in the perspectives of the middle-class rebel, and are thereby pushed to the margins of the struggle. The ruling class is thus safeguarded from serious assault. Nevertheless, the present upheaval is going a long way towards breaking the stalemate Stalinism has imposed on the left, making for new opportunities for revolutionaries to break out to a workers’ revolutionary party.

SINCE CHRISTMAS, more than 130 people have been shot dead by the police in India, many of them in the continuous food riots in the states of Gujerat and Bihar. Gujerat has been the home of the traditionally prosperous middle and rich peasantry that supplied an important base of support to the Congress right wing. The agitation began with a student protest against higher canteen prices, spread rapidly to the cotton-mill workers of the capital, Ahmedabad, and from there to the rest of the state. Rioting continued until the army was ordered to take over the cities.

The revolt was not simply a matter of a food scarcity and high prices. The state chief minister and his associates were accused of manipulating the food distribution system to make massive profits. In the end, the chief minister resigned and the state assembly was dissolved; Delhi took over direct administration. Meanwhile, the revolt had spread to the student movement of Bihar.

These two states have made the headlines. But this is only the most dramatic sign of the disintegration of the country. There have been a rash of communal and religious riots in other states-in Maharashtra (especially in Bombay), in Mysore, in the largest state, Uttar Pradesh, and now in Delhi, where there was a clash between Hindus and Muslims. Members of the Untouchable caste have formed a new political party, the Dalit Panthers, which has demonstrated and clashed violently with the police several times in Bombay. The tribal peoples of Maharashtra are also beginning to demand equal rights with the rest of the population.

Simultaneously, many of the best organised groups of workers have been agitating or on strike – after a lull in 1973 – for some means to safeguard themselves and their families against a terrifying level of inflation – 50 per cent in the past three years; 27 per cent in 1973. Jute and cotton mill workers, railwaymen, insurance and government employees, numerous professional groups, all have struck in the past few , months.

Beyond the employed workers Ii6s the great sea of unemployed and underemployed, now perhaps numbering 40 million or more in the country as a whole. A recent advertisement for 17 social education officers in West Bengal (salary £15 per month) attracted 100,000 applications. The short list for 90 posts as canal inspectors in Marathwada (Maharashtra) last month had 1,810 candidates. The candidates protested when they presented themselves for interview because the interviewer had not bothered to turn up. The police opened fire and two were killed.

These are the symptoms of possibly the most profound crisis that has ever affected India. For years the economy has decayed, but only over the past few years have the real results of this decomposition become apparent.

The economy has been in decline since the end of the third five-year plan (1955-6). A plan holiday symbolised the government’s inability to restore economic growth, let alone accelerate the rate of creation of jobs. Defence became the most dynamic sector of the economy, supporting great power exploits abroad as the circus that would console people for the lack of bread. More expenditure on defence meant less to create jobs or assist agriculture, so that ultimately poor employment and the danger of famine become the two symptoms of the failure of India’s ruling class. The world downturn came upon an already sickly Indian economy. In 1973, inflation increased while industrial output stagnated, producing a decline in average real income per head to about £44 per year.

On top of this had been added the increase in oil prices. Oil imports could take up to 80 per cent of the country’s export earnings, making impossible significant imports of foodstuffs, fertilisers, industrial machinery or raw materials. The balance of payments difficulties of the Western capitalist countries makes it impossible for aid to bail out the Indian economy. In any case, aid has been falling for a long time for political reasons – from two dollars per head of the Indian population in the mid-1960s to just over 50 cents now – and mere hunger will not reverse the trend. Foreign investment in India is also falling. Russian assistance has increased sharply but it is small beside the overall gap if the economy is even just to keep going, let alone grow – the World Bank estimates aid must increase two and a half times over if the country is to cope.

Oil imports are vital for transport, fertilisers, kerosene – the main source of heat and light in rural areas, power for irrigation and tube well pumps, for power in major industries, for herbicides, even for drying tea, an important export. They affect directly the ability to export – so that, for example, food can be imported – and the capacity of agriculture to grow foodstuffs. Stocks of food are very low. They were reduced through 1973 in making up for the poor harvests of 1972.

The scarcity encourages hoarding and speculation by rich peasants and traders. Last year, the government tried to overcome this – and make a gesture to the left – by nationalising the wholesale trade in grain. The effect was paralysing since the traders refused to sell to the government. One of the results were the food riots in Gujerat. Now the government has scrapped its monopoly and increased its purchasing price by 40 per cent – giving a massive profit to the hoarders Wheat stocks in the world are low and prices very high, so to make up the deficit with imports only reproduces the central difficulty. A small variation in the rainfall this year could produce a very serious famine.

A society reduced to a crisis of sheer survival has little time for much else. The government has effectively abandoned any pretence of planning or trying to increase economic development. This has steadily reduced the role of the public sector and opened the way for private capital in all the profitable sectors. This is in tune with American pressure to ‘liberalise’ the economy – that is, open it to US capital and exports. Indeed, public capital is now used extensively to finance private profit. The industry which is profitable is that which meets the consumption demand of upper income groups – so while much of India goes hungry, the island of upper-class life flourishes.

The government itself assists this process. Its current budget deficit has been converted by the inflation from 850 million Rupees to 8500 million Rupees, yet still it has made a major cut in income taxes for the richest.

It has also increased defence expenditure – now taking a fifth of the national budget. The role of the military has been vastly expanded; indeed, defence is the only continuously booming sector of the economy. There are no serious external threats to India now that Pakistan has been cut in half. Internally, however, the calls for military assistance have grown steadily and will grow even more in the future. The generals cannot have failed to notice their increasingly important role, particularly when – as happened last year in the largest state in India, Uttar Pradesh – the police mutinied. This year, when martial law was declared in Ahmedabad, the army was greeted on its arrival with enthusiastic crowds, despite a curfew, with garlands and cries of ‘You are our brethren’. Again the generals cannot fail to notice that, amid the corruption, squalor and instability of the civil authority, the army appears as the only honest, orderly and disciplined force.

The government is eager to find scapegoats for its difficulties – Pakistan, Bangladesh refugees, the weather, oil sheikhs. It has also begun to accuse the workers of sabotaging the economy. Mrs Gandhi has proposed a ban on strikes for a few years. There have been two lock-outs in government undertakings, Indian Airlines and the enormous Life Insurance Corporation. K.D. Malaviya, Minister of Steel and famous as an old-time left-wing Congressman, has accused steelworkers of being responsible for the disastrous results in public sector steel, even though man-days lost in disputes declined last year. The two major employers’ organisations have taken up the cry, ‘notwithstanding what the statisticians say’.

The same approach is apparent in the current railways dispute. The Minister of Railways deliberately blocked the long-drawn-out negotiations and then, when the call for a strike went out, moved the police in to arrest 15,000 railway trade unionists.

The non-Congress left – assorted Communist and Socialist parties – have played virtually no role in the massive wave of agitation, other than trying to ride it to advantage, along with every other political outfit. Old discredited politicians have re-emerged to try and make a new career out of disaster. As always, the Hindu fascists and extreme communalists have tried to turn events in their direction, which is why so many of the riots that seem to be about religion in fact have their real source in food and jobs.

The present crisis in India shows the world crisis in its starkest form. Neither private nor state capitalism can grapple with it in any other way than by reducing India to the status of beggar. At present, there is no coherent alternative that fuses the fury of workers and their capacity to seize the state. As a result, Congress is able to totter from one catastrophe to another, and even then it requires more and more massive bribery and violence to achieve this result. The army will not prove indefinitely tolerant. Yet some on the left could still make a difference. For the upheaval now underway is shaking loose of traditional loyalties masses of workers – the grip of the Communist trade unions (AITUC) is weakening. But there is very little time to use that opportunity.

PAKISTAN’S economic problems are less severe than India’s – although this makes very little difference to the mass of people – but its political stability is weaker. There would perhaps be a greater opportunity if a revolutionary alternative existed.

The country made a surprising recovery from the 1971 war with India in which the military rulers lost over half the old Pakistan’s population to the new state of Bangladesh. The new government of Z.A. Bhutto introduced a major devaluation of the Pakistan Rupee (131 per cent) which cheapened exports at just the moment when a world commodity boom increased the demand for Pakistan’s exports.

Bhutto pushed up food prices without a major revolt, and this prompted a strong increase in grain output. Yet his success here was overtaken by world inflation, by the widespread floods of last August and by the escalation in oil prices at the turn of the year. In fact, investment has been falling since 1965, and in 1973-4, the terror of private businessmen at the instability of the regime produced a flight of capital and a massive increase in exports as business tried to get its cash out of the country to safe havens.

As a result, home demand was starved, and scarcity of foodstuffs pushed up prices even more. Bhutto was compelled by the possibility of a popular backlash to ban certain exports – foodstuffs and textiles, particularly – and subsidise key food imports. The private traders resisted so the Prime Minister nationalised the trade in vegetable oil and rice. As in the case of Indian nationalisation of the wholesale grain trade, Bhutto’s measures caused a strike by traders, a scarcity of grain and thus a rapid increase in prices.

The attack on the private trade only intensified the terror of businessmen and their unwillingness to invest, despite Bhutto’s introduction of massive investment incentives – up to 75 per cent of new investment can be claimed from the government. So Bhutto intervened again, this time to nationalise 31 key companies, the textile trades and all banks, except those in foreign ownership.

The increase in oil prices was the last straw. At current prices, Pakistan’s oil bill increased from 37 million dollars in 1970 to 85 million in 1973, and an estimated 260 million this year. As in India, increased oil costs reduce food imports and cut home food production through its effects on fertilisers, kerosene, fuel and transport oil.

The effect of all this on popular living standards is grim. Yet the reaction so far, in comparison to the revolt of 1969-70, has been muted, partly because of the threat of Indian intervention, partly because of the weariness of a people faced yet again with a major struggle.

Where there is a major revolt is in the border provinces of Baluchistan and North-West Frontier, but this is a tangled conflict between tribal aristocrats and the central government rather than a popular movement. In Baluchistan, the rebellion is sufficiently large to constitute a civil war, and the Pakistan military behaves as an occupying colonial force. In the third of Pakistan’s four provinces, Sind, there is also a barely concealed hostility to the largest province, Punjab, which broke out not long ago in riots in the city of Karachi. All three provinces sport movements demanding greater local autonomy with a hint of the right of national self-determination.

But the conflicts are still very much within the ruling class of Pakistan. They are expressed in political assassinations, political arrests – more than 200 in Frontier provinces, the tight censorship of newspapers, and the dismissal of some of Bhutto’s key gangsters in the provinces that used to support him most strongly – his cousin, the Chief Minister of Bhutto’s own province, Sind, and his declared political heir, the Chief Minister of Punjab. The rash of strikes and demonstrations has yet to assume the drive of the 1969 movement.

Pakistan is now also the victim of international politicking in a way it could not be before 1971. Russia is both trying directly to oust Chinese influence from Pakistan by bribing Bhutto with aid, and supplying heavy assistance to India and Afghanistan, Pakistan’s neighbours. In turn, India is supporting Afghanistan, which lays claim to the Pathan people of Pakistan’s Frontier provinces.

Iraq has a long running battle with Iran, and as a result, supports the movement for a Greater Baluchistan covering Baluchis on both sides of the Iran-Pakistan border (Iraq tried to smuggle arms to the Baluchis through its embassy in Pakistan). Iran has always been opposed to the Arabs, and so was able to ally with Pakistan, but now Bhutto’s attempt to win Arab support has pushed the Shah into association with Mrs Gandhi.

However, the game of perpetual manoeuvre is not ended, for Bhutto has now counterattacked by reaching an agreement with Bangladesh and so frightening those in New Delhi who regard Bangladesh as legitimate Indian property.

In the end, the permutations indicate no more than Bhutto’s desperate struggle to survive amid predatory neighbours, each of which would gladly take its share in an eventual carve up of Pakistan. But that is only a dim threat. The real challenge comes, not from abroad, but from a people made desperate by the unrelenting pressure on their living standards from an intractable world market. The size and privileges of the military establishment – justified by Bhutto on the grounds of the foreign threats – is only an obscene reminder to most people of how unequal is the sacrifice asked of them.

In 1971, the military rulers stifled the Pakistan revolution by turning it into a savage attack on the Bengalis in what was then East Pakistan, and into a war with India. The two arms of the revolution had been the national revolt of the Bengalis and the class struggle in West Pakistan. But the first was used by the military to defeat the second, instead of both contributing to the same aim – the overthrow of the military.

The military, by their assault on Bengal, produced what they always claimed they were seeking to avoid: a war with India and their own massive military defeat. Nevertheless, Indian intervention allowed the military in the West to consolidate their rule, now with a civilian disguise in the shape of Bhutto. By causing Indian military intervention, they bequeathed to the new Bangladesh the weakest and most corrupt new government under Indian patronage, they permitted Mrs Gandhi, by achieving a temporary popularity, to root out the strongest section of the Indian left, in West Bengal. All round, the Pakistan military is owed a debt of gratitude by the ruling classes of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.

Now the scene is being partly played through again but with a weaker national revolt (on a border not with India but a much weaker power, Afghanistan) but under much more severe economic conditions. The military will again try to use the threat of foreign intervention when the revolt in the outlying provinces threatens to unite with the class struggle in the Punjab. The unification of those two movements could end the paralysis not simply of Pakistan but of the whole subcontinent.

THE SITUATION in Bangladesh is undoubtedly the worst in South Asia, one of the worst in the world, and probably the worst in the history of East Bengal, which made up the new state. A population of 75 millions, increasing by more than two millions each year, lives in an area half the size of Britain at an annual income of roughly £25 per year per head. The country, exploited over the years since the British left by the old state of Pakistan, when Bangladesh was East Pakistan, ransacked during the 1971 repression of the Pakistan military and the Indian invasion, scarcely exists as a coherent entity.

The weak corrupt government which India and Pakistan bequeathed to Bangladesh is little more than a holding company for the local gangsters who run the districts of the country, have a hand in land, trade and public office. The government party, the Awami League, is now notorious for its corruption, for maintaining a speculative economy, and above all, for smuggling out of the country into India both grain and jute, the country’s main export.

Because the government has never properly established its writ over the whole country, each gangster maintains his own private army with which to ward off rivals. The result is not unlike the Wild West: street warfare, regular murders, the ransacking of villages, the disappearance of people, hoodlums seem supreme. Mujibur Rahman, the Prime Minister, also has a paramilitary force, the Rakki Bahini, which has now been empowered to stamp out violence, to search and arrest without restriction provided it ‘acts in good faith’.

In good faith, no doubt, more than 10 MPs have been murdered, hundreds of Awami League officials slaughtered, one of the opposition headquarters sacked. There have been four murderous attacks on Dacca University hostels – in the last one in April, seven students were seized at night and murdered. This is an attempt by the youth wing of the Awami League to destroy its student wing. The students arranged a protest march; two hand grenades were thrown at it, and two student leaders arrested for ‘attempted murders’. This is the rule of law offered by Bengali democrats.

While the gangsters slog it out, Mujibur Rahman presides benignly above, and the mass of the population struggle against sporadic famine below. In the past fortnight, Dacca newspapers have reported 32 cases of death from starvation, peasants offering their children for sale because they cannot afford to feed them, families committing suicide to escape. With large scale smuggling of grain out of the country by the Awami League – perhaps more than one million tons in the past year, food depends on what can be grown and upon imports. Food imports took 40 per cent of the total import bill last year.

Increasing food output and paying for imports requires exports, particularly, jute and tea. Yet those peasants able to do so are growing food instead of jute since even with a good jute price, it is not possible to buy much food nor is it easy to ship jute to the ports with such a chaotic transport system.

The increase in oil prices only increases the difficulties of restoring the economy. The distance that would have to be travelled to get back to the conditions of 1969-70 is immense. Industrial output is 30 per cent below what it was then, jute production 28 per cent, cotton yarn 23 per cent, sugar 80 per cent, exports 30 per cent, and tea exports – despite a 30 per cent subsidy to the tea growers – 60 per cent down. The scarcities generate an uncontrollable inflation. Basic prices have increased between one and four times over since 1970. Coarse rice prices have more than doubled. Unemployment is very substantial in a population now larger than in 1970,

The government does little more than hang on, hoping the storm will blow itself out. Mujibur Rahman started as a client of the Indian government, and India inevitably dominates the economy, whatever the protestations of Delhi.

But Mujib is too astute a politician not to use India as a useful explanation of the disasters, and even re-establish relations with Pakistan. ‘The people have short memories’, as he put it recently. Despite all the pillage and savagery of the Pakistani army, despite the central role of Bhutto in the politics of the destruction of East Bengal, Mujib now prattles:

‘I am impressed by Mr Bhutto’s sincerity. I am overwhelmed by the love and affection shown me by the people of Pakistan.’

Pakistan is a counterweight to India, and is the road to reconciliation with China, an even bigger counterweight to both India and Russia.

The left has never recovered from the disasters of 1971. To a greater or lesser degree, it supported the unity of Pakistan against the Awami League – partly because the military were in alliance with China. As a result of its confusion at China’s role, many socialists failed to appraise either the role of Mujib or the role of India. To this day, much of the left still pins its hopes on Mujib imposing his will on the warring factions of the Awami League. The only alternative seems to be to retreat to the villages and form a guerrilla band.

In practice, without a secure class basis and in a disintegrating country, the left is reduced to sniping from the wings. Yet an army cannot be built in the midst of hand-to-hand fighting, nor can those on the sidelines influence the outcome. Critical support for Mujib or playing soldiers in the villages are both part of the old illusory politics that led to the last catastrophe. But no force seems spontaneously capable of breaking these illusions, and when China recognises Bangla-desh-and perhaps nominates it for entry to the United Nations – the confusion will be compounded. Meanwhile, the real victims face an almost endless prospect of deterioration, punctuated only by disaster.

AS IN THE other countries of South Asia, the world crisis of capitalism has hit Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) very hard, particularly since it comes at the end of a long period of economic stagnation. The domestic food supply depends in part on imports – food imports were 44 per cent of total imports in 1972, and increased last year. For 20 years, exports (tea, rubber, coconuts) have stagnated while imports have increased. The gap between the two has been covered by borrowing abroad. Now about a third of the country’s export earnings go to pay interest on past loans, and the terms of any new loans grow harsher each year.

Last autumn the International Monetary Fund refused yet another request for a loan unless the Rupee was devalued, which would have increased the price of imported food and so imposed a real wage cut. The government proclaimed that it would never bow to the imperialist agencies, and promptly raised food prices and cut food subsidies itself. This was part of a continuing struggle by the government to cut food consumption. Last October, Mrs Bandaranaike’s government cut the rice ration by three quarters – now it is down to one pound per week per head, doubled the price of bread, cut the sugar ration and increased the price. It is now illegal to transport, possess or sell rice in quantities larger than the individual ration.

All this was to safeguard the government’s procurement of rice for distribution as rations, but in effect it robbed the sellers of any market. As the gap between the government and the black market prices widened, procurements dropped – to 75 per cent of normal in late 1973, 20 per cent in January of this year. At that point, the government went into reverse, as in India, increasing the price paid for rice and searching foreign countries for rice imports – from Pakistan, India, China and Russia.

Paying for oil imports cut into food supplies. The Middle Eastern suppliers have been as unrelenting as Western imperialists in this respect. Iraq refused to supply oil at the price contracted originally (£1.70 per barrel), and insisted on the Sri Lanka government depositing £5.80 per barrel in a foreign bank before reconsidering supplies. The price of oil along with the cost of debt servicing could wipe out the possibility of paying for food imports.

All this comes upon a population already poor. There are possibly three quarters of a million unemployed, 17 per cent of the labour force. While food remains a crisis question, the resources necessary to expand the creation of jobs ate not. available. Scarcity adds further fuel to inflation: in four years, the cost of living has increased by 50 per cent. With the government’s cuts in the rice ration and welfare provisions this becomes an intolerable stranglehold on the mass of people. The conditions for most people have deteriorated since 1971 when thousands of young people were provoked into revolt. About 5,000 were killed and 16,000 arrested.

Where is the left in this situation? The main part of the Sri Lanka left constitutes the government of Mrs Bandaranaike This is full of left-wing talk – and gestures of nationalisation – but in the end, agrees to act as agent for the world crisis. This means essentially defending the privileges of the ruling class by imposing on the people of the country the cost of rising world prices. Beneath the facade of ‘democracy’, corruption permits a few to escape from the public crisis. They say that there are 200 relatives of the Prime Minister now employed in the key offices of state.

The three main newspaper groups have been shut down or curbed in order to prevent any public challenge. When the right-wing opposition party, the UNP, tried last month to organise popular protests against rising prices, the government first introduced regulations to ban public rallies, and then imposed a national 28-hour curfew.

There are rumours of plots and preparations just as there was before the explosion of 1971. But now, after the experience of 1971, the state is much more heavily armed. The defence budget was doubled in 1971, and rearmament was much speeded with the generous help of ruling classes abroad (including China). Conditions have deteriorated since then, but the defeat of 1971 cannot have left potential rebels unaffected.

As Sri Lanka slides slowly into being an inefficient and corrupt police state, the only organised group likely to provide some obstacle to the government’s intentions is the trade union movement. But even here, although the strength is available, the political orientation of the militants is still towards guerrilla warfare rather than the dictatorship of the proletariat. That makes a mass movement impossible, and means that as the country lurches downwards, it will be the army that inherits.

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 26.2.2008