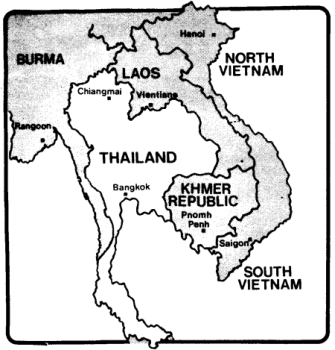

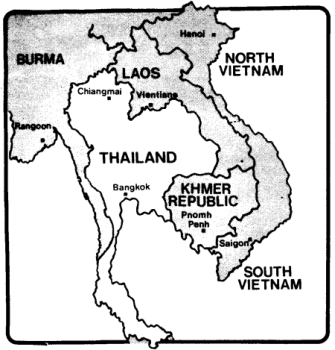

Map showing neighbouring Laos, Cambodia & Vietnam

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Notes of the Month, International Socialism (1st series), No.93, November/December 1976, pp.8-9.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

|

Map showing neighbouring Laos, Cambodia & Vietnam |

Nigel Harris writes: On October 6th, the Thai armed forces once again seized power, their fourteenth coup in forty years. This time however the scale of savagery was extreme – forty were killed and 100 injured in the first day. 4,000 were arrested at the same time, including most of the leadership of the student, trade union and peasant movements, the political parties and the press. Political parties are now banned, the press tightly censored, and over one million books, pamphlets and documents have been seized from libraries and bookshops for burning.

The extremity of the official violence – garrotting, throwing petrol on victims and igniting it, grenade and rocket launcher attacks on the unarmed – is ‘law and order’s’ response to the scale of the class struggle.

Exactly three years ago, a half million demonstrators frightened the military chiefs and the king into ditching the triumvirate in power, including dictator General Thanom Kittikachorn and police chief General Prapas. It was unprecedented in Thai history that a popular movement could have had such effect. It demonstrated that the students had been able to gain the support of an entirely new force, the Thai working class, created in the 1950s and 1960s. In a panic, the older order conceded elections, political parties and a free press, but not legal trade unions (that did not come until January 1975).

The following year saw an explosion of militancy. The strike rate doubled (see that graph) [1*] on the staggering score of 1973; workers began to raise their desperately low pay, beat back the foremen’s gangsters and improve conditions. There was an answering call from the peasants, and a rash of new peasant associations began to agitate for land (in the north-east and north), and lower interest rates and higher rice prices in the central plains. The Muslims of the South again became active against Thai Buddhist oppression. The student movement turned sharply Left. They began to raise socialist demands, to attack the dominant position of foreign capital in the country, and the presence of 39,000 US troops and a string of American military bases.

The seams of the whole society appeared to split. The atmosphere was electric. For example, when the Bangkok police locked up a taxi-driver in July, 3,000 rallied to his support and fought a three day gun battle with the police.

|

Thailand Population: 39 million Industrial safety History |

The new Government tried to make concessions – of increases in the minimum wage to ward off the demand for legal trade unions and national bargaining rights; of a weak land reform and rent control to divert the peasant movement; of regular consultation between the prime minister and the National Student Centre to disarm opposition. Yet each concession seemed only to increase the agitation.

The Right began to organize. The army’s Internal Security Operations Command financed a wave of physical violance against the leaders of the revolt. Navapol appeared, a political thug organisation, with its own paramilitary youth organisation, the Red Gaurs, aiming to split the student movement between the university and technical college students (the technical students bore the brunt of the 1973 fighting, but inherited very little of the prestige afterwards). Whenever the National Student Centre called its factions to a united demonstration, Navapol’s armed squads were there to beat them up under the banner of the ‘Anti-Communist Imperialism United Front’. Towards the end of 1975 and into this year, some 35 Left and liberal party and student leaders, trade union leaders, and 21 chairmen of peasant associations were murdered. Party and trade union headquarters were bombed, and opposition party candidates intimidated to withdraw.

Yet it did not kill the militancy. In January of this year, the Government raised the price of rice by 30 percent. The Federation of Trade unions called a general strike for five days. The Government caved in. There were new elections in April, and a more Right-wing coalition formed a new government under Seni Pramoj. Simultaneously, the student movement continued its massive campaign against the US presence in the country. Despite the open hostility of the military, they forced the Government to push much of the US military forces out (’American advisers’ remain, plus US air landing rights and a secret tracking station).

It could not last. Wages began to rise rapidly. There was a strike by private investment, and the inflow of foreign capital dried up. The victories of the liberation forces in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos brought the red tide lapping to Thailand’s borders – just at the moment when the demonstrators had forced an American evacuation. The hysteria of the Right became insupportible. Now the king publicly warned of the ‘sabotage of our kingdom’. The military called alerts to try and deter the students, and continued holding martial law in 28 provinces. In April, at a birthday cocktail party for the armed forces chiefs, the Supreme Commander urged them to patience, saying ‘I will tell you when the time comes.’

The time came in October, no doubt by courtesy of ISOC. The bodies of two Left-wing activists were discovered hanging from a wall outside the city. The police subsequently admitted responsibility for the murders.

The Left could no longer restrain itself and demonstrated, demanding trial of the policemen concerned. It was the opportunity ISOC and Navapol had awaited. Watched impassively by the police, masses of Right wing thugs drove the students into the campus of Thammaset University, and then turned to demonstrate before Seni Pramoj, demanding the Government clean up the country. The final signal was broadcast from the Armed Forces radio: armed thugs and 1,000 police with special warfare units then deluged the university campus with heavy fire. They then raced through it, throwing grenades into the lecture rooms, beating up any any unlucky enough to come in their way. At the same moment, Supreme Commander Admiral Sa Ngad, two days earlier appointed Defence Minister (Seni Pramoj’s attempt to placate the armed forces) seized the Government.

Thailand went into a revolution in 1973 but without a revolutionary party. The Thai Communist Party has throughout the events of the past three years been hundreds of miles away from the scene of the action, Bangkok, holed up in the hills of the north-east fighting guerilla warfare. The needs of the city struggle was an immediate political alternative to the old order which remained still in power despite what had been won in 1973. But the guerillas of the CPT aim to encircle Bangkok only after twenty years of ‘protracted struggle’. Without a revolutionary party, no systematic efforts were made to capitalize on the discontents of the troops of in the lower echelons of the State bureaucracy. The oligarchy’s truncheon remained intact. Above all, the rebels in the main failed to understand that the movement could not stop halfway as a stable permanent extra-parliamentary opposition. The regime – the military, and its US backers, Chinese and foreign business, the corrupt upper layers of the bureacuracy – could not tolerate indefinitely the revolt from below. Either the old order would have to smash the rebels, or the rebels had to create a new order and annihilate the oligarchy. The Government was no more than a weak facade for the old order’s power, yet the student movement felt it had won a victory when the Prime Minister consulted it.

The war is not over, but the events of October 6th are a heavy defeat for the Thai working class. The victories they have won in the past three years are now disintegrating. The leadership is dead or gaoled or has fled. Some of the students will conclude that the perspective of guerilla warfare and ‘protracted struggle’ is now abundantly confirmed, failing to see that the defeat is partly the responsibility of their leadership. They will flee to the north-east, and the workers will once more be thrown back on their own resources. They have shown abundantly once again the capacity of workers to transform the political scene, to develop with staggering speed, and the decisive importance of a mass workers revolutionary party dedicted not to influencing the State but to smashing it. They return to silence and to memory.

1*. No graph is printed with the article.

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 3.2.2008