Source: Eurostat and IMF

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism (1st series), No.100, July 1977, pp.27-35.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

SINCE 1973 the structure of international capitalism has been disrupted as a result of the world economic crisis. The pattern of relationships that developed in the post-war years has undergone a series of changes. The most significant of these changes have reproduced some of the structural features of capitalism as it appeared to Marxists at the time of the first world war. One obvious example is the increased importance of the raw materials produced by the less developed countries (LDCs) since 1973. Another is the reappearance of what Lenin and Hilferding called ‘finance capital’ – the growing centralisation of international economic power in the hands of the Western banks.

In sum, the changes have two aspects. On the one hand, they represent much greater centralisation of the world system and its component national parts, a centralisation which increases the synchronisation of both the economic movement of the components and the social response. On the other hand, the parts of the system are increasingly differentiated, much more unstable in their relative standing. This article analyses both these features – the centralisation and the differentiation – as well as the rhythms of revolt they have produced.

IN ORDER to understand these changes we need first to look briefly at the structure of world capitalism. The starting point for Marxist analyses of imperialism was its most obvious feature in the years before 1914 – the colonisation of Africa, Asia and Latin America by the advanced capitalist countries of North America and Western Europe (MDCs, or more developed countries, is the current cliche). The Marxists of the time – Hilferding, Luxemburg, and especially Lenin and Bukharin – argued that colonialism arose out of the basic structure of the imperialist economies. The colonies provided the advanced capitalist countries with markets, the raw materials and the outlets for surplus capital. They thus served both to offset the tendencies towards crisis inherent in the system and to provide the arena for fierce inter-imperialist rivalries leading to world war.

The system that emerged from the second world war differed from this pattern in a number of ways. The permanent arms economy that evolved out of post-war military competition between the Western and Eastern blocs offset the tendency towards crisis while reducing the advanced capitalist countries’ dependence on the colonies as a stabiliser. The drive to self-sufficiency produced both by war economies and inter-war protectionism encouraged massive import substitution so reducing the need for the direct control of the sources of raw materials in the LDCs. As a result, the LDCs’ share of world trade fell from about a third in 1950 to 14 per cent in 1970. The pattern of international investment also shifted, away from the LDCs towards the technologically advanced industries in the MDCs – for example, automobiles, electronics, chemicals. The main flows of capital and commodities took place between the MDCs themselves.

Political independence could, therefore, be conceded to the colonies without severe disruption of the world system. Once independent, the countries of the Third World’ found themselves condemned to compete in a race they could not win. The prices of the raw materials they exported fell relative to those of the imports from the MDCs needed to industrialise. The scale of investment required in order to compete with the MDCs was well beyond the resources of most of the LDCs.

WE HAVE left the stability of the 1950s and 1960s behind us. The decline of the permanent arms economy has been accompanied by a world-wide crisis of profitability, intensified international competition and the worst recession since the 1930s. The problems have been exacerbated by a new development – the spread of industrial capacity across the globe.

This development has disrupted the pecking order among the industrial economies of the world. World trade is still dominated by the MDCs – to be specific, by the giant United States economy and two smaller advanced capitalist countries, Japan and West Germany. The Soviet Union is the fourth giant of world production – in 1971 its gross national product (GNP) was about a third of that of the United States, but still a third larger than Japan’s.

Beneath this four are the rest of the MDCs – the other members of the Western capitalist bloc and the COMECON countries. However, there is a tendency for some of these to be superseded in certain fields by a layer of the richer LDCs – Iran, Brazil, Argentina, Nigeria, Indonesia, South Korea, India and Mexico. The same is true of southern European countries like Spain, Portugal and Greece. Their situation is one of low income, high unemployment and concentrated industrial capacity.

The spread of industrial capacity to certain LDCs has rendered the problems facing the advanced capitalist countries more acute. This year the Hyundai motor corporation of South Korea exported samples of its cheap car, the Pony, at a price competitive with Japanese vehicles. Ironically, Hyundai’s tooling and its top management were provided by British Leyland, although South Korean competition can only drive Leyland even closer to bankruptcy. The growing competitiveness of these new industrial producers is one factor underlying the changes in the world system analysed in this article.

IN THE last boom (1972-1973), the system experienced grave shortages of almost all types of raw materials, a shortage made extreme by the instability of currencies which obliged traders to move out of unreliable cash into commodities as soon as possible. The greatly increased demand for raw materials is partly shown by the fact that the share of the LDCs (the exports of which are mainly raw materials) in world exports increased from about 14 per cent in 1970 to 27 per cent.

It was a brief moment before slump destroyed the demand for the exports of the LDCs and the Eastern Bloc. But the slump did not end the inflation in the manufactured exports of the MDCs (the imports of the LDCs) nor did it prevent the increase in the price of oil which afflicted the imports of many LDCs which do not produce oil. The majority of the world’s countries moved into massive trade deficits. For example, the Philippines trade balance deteriorated by 45 per cent between 1974 and 1976; its oil import bill increased from $190 million to $800 million. [1] The old pattern of world trade, dominated by the exchanges of manufactured goods between the MDCs, tended to return to an earlier pattern in which primary commodities, raw materials, had a much larger role to play.

The majority of governments were faced with gigantic deficits in their trade. They were supposed to overcome the problem in the orthodox wisdom by cutting back domestic consumption until imports fell and balanced the external trade account, ‘adjusting domestic to international prices’. The process would be less painful if exports expanded simultaneously. Cutting imports is cutting the rest of the world’s exports, and if pursued by enough countries (as happens in a general slump), is itself catastrophic for the system. Of course, few ruling classes could pursue any such policy without being engulfed in a tide of popular fury. As it is, modest efforts were made in this direction, while the government borrowed heavily abroad to cover the current deficit in the hope that the world system would return to boom and so stimulate the expansion of exports before the repayment of loans became due.

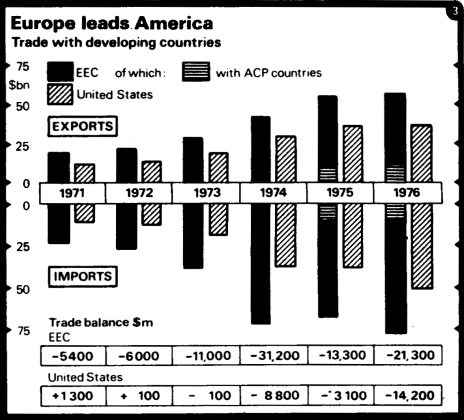

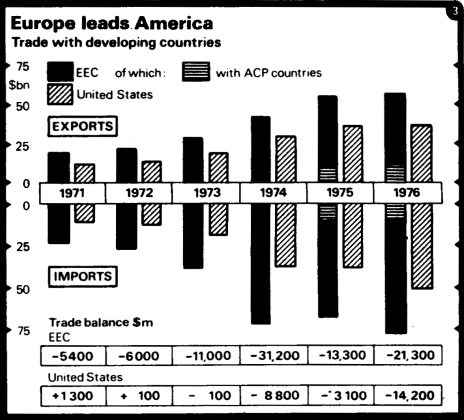

Western private banks, faced with a contraction of borrowing in the MDCs, were only to eager by providing short-term loans to the LDCs and Eastern Europe to sustain their profits. The loans were used in part to finance industrial imports from the MDCs, so keeping up the demand. As a result, the MDCs have become more dependent on exports to the LDCs. Currently, 36 per cent of the exports of the European Common Market go to LDCs, 21 per cent to non-oil producing LDCs (cf. the graph). However, important as the shift has been, it has not prevented the continued rundown of some of the core zones of the MDCs – the West Midlands, the Ruhr, Lorraine – and the collapse of important companies.

|

|

Source: Eurostat and IMF |

The volume of LDC indebtedness soared. In 1971, when the cumulative debt of the LDCs was about $60 billion, governments were obliged to use such a large and increasing share of export earnings to pay the interest and annual repayments, that the debt threatened to strangle development efforts. However, now the cumulative debt is over $180 billion, equal to two year’s export earnings for all the LDCs put together. About $75 billion of this is owed to Western private banks, for short term finance and therefore carrying very high interest rates. Much of it becomes due for repayment in the next four to five years. Interest and amortization is adding about $20-25 billion per year to the total debt, and will continue to do so up to 1981.

Some 29 countries account for 70 per cent of the debt, and a much smaller group for the major part of this – particularly Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Zaire, South Korea, the Philippines, most of them among the fastest growing LDCs. The burden of debt servicing (interest payments etc) on current activities is substantial. For example, Mexico is supposed to repay in loans and interest this year $5.1 billion; on the current budget, the government can raise only 15 per cent of this, so it must borrow the rest abroad just to stand still. Brazil at the end of 1976 had a cumulative debt of $27 billion, compared to the value of its foreign trade of $21 billion and reserves of $3.4 billion. By comparison, Britain’s cumulative debt this year is $22 billion ($17 billion repayable between 1979 and 1984, reaching a peak repayment of $4.7 billion in 1981; the annual interest payments are currently $1.3 billion).

By 1975, servicing costs alone were said to be equivalent to 17 per cent of the export earnings for most LDCs. In international lending, there is a conventional ‘danger point’ when debt servicing takes more than 20 per cent of a country’s annual export earnings. It is at this point that countries are in danger of defaulting on their payments; if they do, the repayment of the cumulative debt is threatened, a country can secure no credit and its imports and exports dry up. On the other hand, sustained default can bankrupt a Western bank, possibly precipitating a financial crisis and slump in the advanced capitalist bloc (in the 1930s, six Latin American countries defaulted when the debt servicing-export ratio rose above 20 per cent).

The smaller a country’s export earnings, the easier it is to reach the ‘danger point’ with quite small borrowings. The servicing of India’s cumulative debt ($13.1 billion, as against reserves of $3 billion) takes nearly a third of the country’s export revenue (and its estimated foreign exchange needs for the coming three years are put at a further $13.1 billion).

Already there have been some temporary defaults or very near risks – in Zaire, Peru, Argentina, North Korea, and Indonesia; Egypt was ninety days late on its payments in 1976. A political crisis such as occurred recently in Zaire or is currently occurring in Pakistan exaggerates the risk of default and exposes the vastly increased vulnerability of the financial system to a collapse of confidence.

At first, the oil producing countries (OPEC) were protected from the crisis by their increased revenue as a result of the oil price increase in 1973-74. But the ‘surplus’ they received has rapidly declined – from $66 billion in 1974 to possibly $32 billion this year (and a predicted $20 billion by 1980). The larger OPEC countries tried to expand out of the world boom by accelerating their spending abroad (for industrial imports, for arms, and by purchasing assets in the MDCs). Currently, half the 13 OPEC countries are now in deficit, so some of them are now also obliged to borrow to keep up their domestic growth (Iran $1.4 billion, Venezuela $1.2 billion, from the Eurocurrency market alone). As a result, the ‘surplus’ is now concentrated in the hands of three tiny Middle Eastern oil producers (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, which means mainly Abu Dhabi).

The growing role of the rulers of Saudi Arabia summarises some of the new trends in the world economy. Saudi Arabia’s control of a large portion of oil production makes it indispensable to the economies of the MDCs. At the same time, its share of the OPEC oil surplus makes an essential part of the new system of international finance capital, since billions of Saudi petrodollars have been lent to Western bankers. The new economic power of the Saudi regime is accompanied by its growing political role as a defender of Western, and in particular American, interests in the LDCs. Examples are Sheikh Yamani’s role in opposing last December’s OPEC oil price increase and in pressing the Western governments’ proposals on the representatives of the LDCs at the North/South talks in Paris, as well as growing Saudi intervention to defend the status quo in countries as diverse as Lebanon, Zaire and Pakistan.

At the other end of the debt relationship are Western banks. They have, through the crisis, greatly expanded their international dealings. In Britain, Lloyds and Barclays have become important in this lending, launching themselves as multinational banks. US banks have expanded their loans to foreigners by 20 per cent year for the past three years. One of the largest operators. Citibank, has 63 per cent of its current loans abroad at the moment, earning 72 per cent of its current profits. Cumulative US bank loans abroad at the moment are some $45 billion. West German banks have also expanded external operations rapidly, particularly in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Japanese banks are still mainly involved in operations at home; the largest, Dai Ichi Kangyo, gets about 11-12 per cent of its annual profit abroad.

Some of the US and European banks have become very exposed to the risk of default and so the possible precipitation of their own bankruptcy. It is for this reason that Arthur Burns, head of the US Federal Reserve Board, has been issuing warnings to US banks not to extend themselves further and intervening to forbid certain loans.

It is also the reason why the International Monetary Fund (the MDC’s central bank, set up to offset sudden payments crises) is being vastly expanded to supervise borrowing countries, using its lending power to force governments to cut imports and raise exports. Argentina and Zaire have both had their debts ‘reorganized’ by the IMF to protect the Western banks’ loans, and the IMF is currently supervising Mexico, Brazil, Britain, Italy and many more. The IMF’s current assets (usable currencies to the tune of $4 billion) are quite inadequate to the task, compared to a total world deficit of $45 billion (with a $4 billion contribution extracted from Saudi Arabia). IMF intervention exaggerates the scale of the crisis in the world system (by cutting imports and increasing exports) as well as inflicting the maximum damage on domestic consumption. The results can be seen in Egypt in January when the government endeavoured to ‘cut domestic consumption’ by raising food prices to the international level.

Even without IMF supervision, the lending relationship imposes a two way discipline. It obliges the borrower to slash the living standards of the country concerned (and reduce the public sector, supposedly ‘part of consumption’), but it also obliges the lender to keep up the loans lest stopping them drives the borrower into default, so bankrupting the banks concerned. Brazil has consciously tried to push up its debts so that the lending banks become desperate to protect Brazil from default. In the spring of 1975, North Korea (in the Eastern Bloc) defaulted on its interest payments. The cumulative debt was about half a billion dollars, and the share of British, French and other banks sufficiently small for them to insist on no further loans until interest payments were resumed. Japanese banks, the main lenders, were however too frightened and resumed lending just to try and ensure ultimate repayment. The banks are competing for custom in a declining market, so that a borrower can shop around if one lot refuses; the US intervened to limit South Korea’s borrowings (a cumulative debt of $6.7 billion in 1976), so Seoul promptly turned to West German banks to raise the cash.

THE SEQUENCE of events which afflicted the LDCs and advanced capitalist countries also affected the Eastern Bloc. Like the leading LDCs, the COMECON group is heavily dependent on imports from the Western bloc for technically advanced inputs. In 1974, the group imported from the West six times as much technically advanced equipment and materials as it exported to the West (machinery, vehicles, plant, chemicals, electrical and electronic goods). Much of the computer technology in the East is dependent upon or derived from the West, and Russian fertiliser output, so decisive for its ailing agricultural production, is manufactured in plants imported from the West. To keep up current output, let alone expand future capacity, the COMECON group, like most of the LDCs and all the MDCs, need to keep up imports. Furthermore, two spectacular harvest failures (1973 and 1975) obliged the Soviet Union to make massive imports of grain from the United States.

However, revenue from COMECON’s exports, already insufficient to cover import costs, suffered just as did that of the LDCs in 1974-75. The COMECON response was the same as that of the LDCs: increased borrowing from Western banks. Between 1970 and 1975, COMECON’s debts

increased tenfold, reaching a cumulative total of possibly $40 billion. With cumulative interest, this figure may double by 1980. At present, the largest borrower is the Soviet Union with a debt of $14.4 billion, but with a relatively strong economy backing it. Poland, with a much weaker economy, owes $10.4 billion. Bulgaria with a smaller economy again is possibly in most danger (it has persistently imported twice as much as it exports to the West).

The debt relationship imposes the same external discipline described earlier, a discipline recognized in the stress on the need to expand exports in most of the current five year plans of the Eastern Bloc and the substantial efforts made to cut imports in 1976. Nonetheless, the world law of value obliges, to a greater or lesser extent, conformity with the imperatives of world slump, the use of world prices in inter-COMECON trade, and to some extent, in domestic transactions. As in Egypt in January, so in Poland in June 1976, the results of this ‘discipline’ have been vividly illustrated. [2]

The two way relationship also operates. In this case. West Germany is most closely involved. Half the West’s exports to the Eastern Bloc come from West Germany, and a major part of West German banks’ external lending is with the East.

THE TIDE of debt does not simply engulf the LDCs, some of the MDCs and the Eastern Bloc. The centralizing discipline of finance – and the homogeneity it imposes on a diversity of borrowers – operates not simply between countries. There is an identical situation within countries. The cumulative debts of New York City are not fundamentally distinguished from those of another country. Indeed, the two way discipline was most clearly illustrated in the case of New York; President Ford refused federal aid to the city up until it was discovered that 546 national American banks had holdings of New York city bonds equal to 20 per cent of their capital; Washington intervened to give short term aid to the city in order to protect the US – and indeed, world – banking system. The same obligation has been incurred by the British Government now it is a major lender to British Leyland, Rolls Royce and sundry others.

Shipbuilding is now heavily subsidized to protect it from the logic of debt and competition. The Europeans complain that Japanese new ship prices are 30 to 40 per cent below the products of Common Market shipyards, and, as a result, Japanese yards won 90 per cent of all new ship orders from the OECD countries in the last quarter of 1976. In steel, only the Italian industry is said to have a higher level of debt (in relationship to the value of its output) than France, and the French steel industry’s debts are put at 104 per cent of its turnover (61 per cent for Japan; 34 per cent for Britain; 18 per cent for the US, and 16 per cent for West Germany).

Governments have moved into keeping alive loss making units because they are unwilling to risk the financial and political instability that results from allowing them to collapse, just as they have borrowed abroad to protect against contraction in the world market. More and more of these pockets of unprofitable capital emerge, the longer the crisis continues; living standards are cut and profitable business taxed to subsidise unprofitable businesses. The more the State does this, the more it prevents the general profit rate rising again and so restoring growth.

The financing of unprofitable activities is only part of the increasing centralization of each national unit in order to offset the external crisis. The degree of State intervention is becoming massive, particularly in some of the LDCs. Thus, Jamaica has nationalized or purchased the three main activities of the island (banks, bauxite, hotels). In India, the State has steadily taken over ‘sick industrial units’, particularly in the two leading industries, jute and cotton textiles, to prevent closures. In Mexico, as the external debt soared, so also there was a major domestic extension of public finance to hold up profits. In South Africa, the budget deficit tripled (a 44 per cent increase in government spending in 1976) for the same purpose, not to assist the two million unemployed.

The IMF strives to prevent this and force a cut back in public expenditure so that the economy concerned will be reduced to just what is still profitable. Any government which followed the IMF in this task would be committing political suicide. It was the issue of cuts in public expenditure which set off the general strike of the public sector in Sri Lanka (Ceylon) last December and January.

Reorganisation also is accelerated – mergers, amalgamations, the establishment of cartels, the concentration of production. The State and the banks use their lending power to force such changes as the condition of further loans. Indeed, there seems to be a much closer relationship developing between banks and industry, a relationship more characteristic of the situation before 1914 in Germany as the Financial Times recently noted (in commenting on the relationship between the bankers, Morgan Grenfell, and Davy Ashmore International, in winning a major contract with the Brazilian steel industry).

Crisis, then, forces dependence upon borrowing, whether this is an ailing company or city within a country or an ailing country, and this in turn, forces the centralization of the entire system, its common subordination to a handful of core zones in what Lenin called, the Bondholder States. The integration occurs even where a ruling class has dedicated itself for many years to autarchy. Thus Burma, after thirty years of rejecting links with the world system, has this year been driven back to the search for capital imports and foreign markets. We have already noted the case of North Korea. China has, since 1970, vastly increased its imports in order to raise the rate of domestic growth (and so increase its national power). Its exports were severely damaged by the 1974 downturn (although it was protected from increased oil prices by its own oil resources at home), and, after a major balance of payments crisis in the autumn, survived by slashing imports, increasing its sale of gold reserves, and borrowing (short and medium term credit from Japanese and British banks). The new State of Vietnam has just published some of the most generous terms going for the import of foreign private capital. [3] Finally, Cuba’s cumulative debts compelled the country at the turn of the year to rejig its five year plan and make substantial cuts in domestic consumption. Apparently, no domestic arrangements offset the impact of the crisis to any substantial degree.

HOWEVER, a reverse phenomenon to that of centralization is also present as particular national ruling classes endeavour to establish greater control over their local patch of territory. The pecking order of States changes with increasing rapidity, putting formerly comparable countries suddenly at the opposite ends of the spectrum. This is marked among the group of MDCs. Once there was an ‘Italian miracle’, and not very long ago, France was being tipped as the Japan of the 1980s. Perhaps French capitalism would have been able to deliver if world growth had been sustained. As it is now, if North Sea oil gives the British ruling class more room to manoevre, the French ruling class will suffer the final indignity of being overtaken even by the British. Crisis obliged the French to leave the European currency snake (the fixed exchange rates governing trade between Common Market countries) because they were unable to withstand the domestic effects of being chained to the much stronger West Germans. Of course, the weak men of Europe, Britain, Italy and Ireland never even made the attempt to ride the snake.

Even the top three economies (the US, West Germany and Japan) hold no guaranteed position. The United States – as, to a much more limited extent, Britain – holds a strong position in international finance, so its relative (and increasing) weakness in manufacturing is offset in its balance of payments by what are called ‘invisibles’ (that is, of course, no consolation to the unemployed manufacturing worker). The financial weakness of the Japanese ruling class, in the other hand, obliges it to maintain a gigantic surplus on its balance of trade. Last Year, Japan (with West Germany and Switzerland) took $23 billion on trade from the rest of the MDCs). However, despite this appearance of strength, the ruling classes of neither Japan nor West Germany can afford to be complacent about their basic industries.

Crisis has stretched hard some of the key industries of the period since the war. Shipbuilding has already been mentioned. In Europe especially it is in dire straits, with current capacity estimated to be double what is required over the next five years. All the EEC governments now operate schemes which, from the point of view of the long term the West Germans meet 17.5 per cent of the total cost, and offer very extended credit schemes for the rest of the cost), and offer massive financial concessions to foreign buyers, particularly the LDCs; for example, Norway offers 90 per cent of the purchase price to the buyer, a loan repayable over 15 years at five per cent interest, (or half the rate of inflation there). Japanese shipbuilders say these dodges undercut their prices by 20 per cent (but then the Europeans say Japanese prices are 30-40 per cent below theirs). Even with such schemes which, from the point of view of the long term survival of capitalism are insane, it does not at all prevent the infliction of a savage bloodletting on shipbuilding areas, often ones already depressed.

The crisis has similarly afflicted textiles and clothing. In the US, textile manufacturers are pressing the government to ban or limit imports ‘to protect 2.3 million American jobs against cheap sweated foreign labour’. Carter is currently considering quotas (that is, giving exporting countries set shares of current US imports that they may not increase) or tariffs (a heavy tax on imports) for clothing and also shoes. Already, Washington has imposed one stiff duty on shoe imports, as a result of which, there have been lay offs of 10 to 15 per cent of the workforce in, for example, the main Brazilian shoe making area, the Sinos Valley (Rio Grande do Sul). Carter is also considering restrictions on the import of Japanese electronic and television parts.

Some of these problems are at their most extreme in the steel industry. The US steel industry saw exports fall by 48 per cent in 1975 and a further 10 per cent in 1976. Imports of steel increased by nearly a fifth in 1975, and have continued increasing, taking some 14 per cent of the US market in 1976. The American industry, like the British, is old, but the steel companies cannot undertake the required modernization because of their unprofitablility in relationship to current debts. Demanding a ban on imports is their only method of keeping up their profits (and in June last year, Ford was induced to impose quotas on special steel imports for five years). The US industry is most bitter and persistent in its efforts to raise a chauvinistic campaign against imports, claiming that when imports reach 20 per cent of the US market, 96,000 ‘American jobs’ will be lost, most of them in the relatively declining area of the Great Lakes cities (Chicago, Gary, Cincinnati etc.).

The same problems exist in Europe. The EEC has instituted quotas for sales in the Common Market for European steel companies, dividing the market for some products, and proposed fixed prices on the rest to prevent competition between European producers and thus the destruction of the marginal mills (for example, Shotten, mills in Lorraine in France, Walloon in Belgium, and parts of West Germany, all in already depressed areas). It has also encouraged, contrary to EEC regulations, the creation of a steel cartel for Europe, Eurofer, and negotiated with Japan to limit Japanese steel exports to Europe, contrary to GATT regulations. As a result, the US steel companies are now complaining that the agreement diverts 1.5 million tons of Japanese steel to the US market. Yet, with all these measures, the EEC still estimates that the European industry will have to lay off 150,000 steel workers over the next ten years.

In France, the government has just formulated an emergency plan to inject $1.2 billion dollars into the steel industry (which lost Francs 2.3 billion in 1976 and expects to lose Francs 2.6 billion this year). The plan includes a target to drop 10 per cent of the workforce (16,000 jobs) in twelve months, half of them ‘as it happens’, immigrants. Lorraine, heart of the old steel industry, has lost 10,000 jobs since 1970. In Britain, the problems are familiar and the responses are the same. Already, the British have imposed ‘anti-dumping’ duties on some Spanish, Japanese and South African special steel imports.

The Japanese industry is operating at 80 per cent of capacity (13 of the 66 blast furnaces are idle), with a high bankruptcy rate among small steel companies. The external market is decisive here, and although Japanese companies complain bitterly that the revaluation of the Yen has made all steel exports loss making, they increased steel exports 23 per cent last year. This permitted undertaking a major reinvestment plan for the future and tying up the largest raw material contract for iron ore ever ($4.5 billion for 15 years-worth of South Australian ore). Yet there are problems of competition. The Japanese complain the Europeans are dumping steel in a traditional market of theirs, south east Asia, refusing to charge freight from Europe and offering massive discounts.

The instability among the large producers is exaggerated by the output now coming from the new industrial capacity of some of the stronger LDCs. The case of the Hyundai Pony car was mentioned earlier (and South Korea’s car capacity is much inferior to Brazil’s, with Iran coming up behind). Shipbuilding may be contracting in Europe and the US, but the South Korean ruling class is expanding its yards with great speed. Plans are underway to increase capacity from its present 2.7 million gross tons to 4.25 million by 1981 (including the construction of a yard for one million ton tankers, which are so far only on the drawing board): all to break into the Japanese market. Singapore increased its shipbuilding capacity by 65 per cent in 1976. Taiwan launches its first 445,000 ton tanker in June in a yard completed only a year ago (the second largest in the world after Nagasaki).

The same picture emerges in the steel industry. India last year dumped over one million tons of steel abroad at prices below the costs of production. Spain’s small steel exports have received the attention of the British and now the Common Market. Taiwan has just opened a new steel plant (to produce 1.4 million tons by 1978), and has captured nearly 60 per cent of the ship steel scrap industry, all with a view to exporting. Mexico promises a steel output of 10 million tons by the early 1980s. South Korea launched a steel expansion programme in 1971 and has now reached a capacity of 4.5 million tons (with a target output of 8.5 million tons by 1981); in 1976, it expanded steel exports by 40 per cent, and aims to export 1.4 million tons this year. When the expansion of the world steel market is so small, such small volumes of exports can have devastating effects.

Nor is the problem simply in cars, clothing, shoes, shipbuilding, steel and television parts. Brazil and India are becoming modest arms exporters. Brazil is supplying military aircraft to Chile, the Middle East and Africa (as also are Australia and Canada). Brazil is already manufacturing missiles. With a bit of nuclear technology, the 29 or so countries estimated to have nuclear weapons capacity by 1980 will no doubt move into exports to help along their poorer brethren (hence the current squabble between the US and France and Britain over exporting nuclear capacity to Brazil and others). The lean wolves of the ruling classes of the LDCs are already sniffing the chicken pens of the fat wolves of the ruling classes of Japan, Europe and the US. Meanwhile, in the core zones of industry in the MDCs, manufacturing employment continues inexorably to decline.

In sum, then, the impact of the crisis is to produce paradoxical results – increased financial centralization of the whole system with increased differences between the competing States. Some of the leading LDCs are now in a position to compete in certain very important lines of production with the MDCs, and some of the MDCs – like Britain and Italy – are slipping backwards to the position of LDCs in some sorts of output. Each national ruling class meanwhile tries to offset the external depredations by offloading the cost into the local population and by state intervention. This is the background to the startling reappearance of some of the key features of Lenin’s picture of imperialism, and a reversal of some of the dominant world trends in the 1950s and 1960s. [4] The three leading powers, with possibly half the world’s manufacturing capacity and a larger share of world finance, have become synchronized in their economic movements. They thereby impose on the whole world economy a single rhythm. The common reaction of the world’s ruling classes to this rhythm in turn has created a surprisingly and increasingly synchronized rhythm of revolt.

The world system in crisis removes from most of the national ruling classes much of their freedom to manoeuvre, to control their national patch on key questions, let alone to direct it towards growth. The effective collapse of national five year planning – the summary of the aims of a national ruling class – is an index of this loss of power. Five year planning requires both stable domestic control by the State of a major part of the national surplus and a stable external environment, particularly in trade and cash transactions. Without these, planning just becomes a once-in-awhile propaganda exercise, with no bearing on real government policy. In practice, government policy in a majority of countries is nowadays subordinate to the imperatives of short-run survival without any aspiration to long term aims.

For ruling classes that have aspired to transform the countries they govern, this situation produces demoralization. Each member of the class is increasingly tempted to subordinate the collective long term interests of the class to short term private gains, through corruption and the ‘flight of capital’ (both of which are votes of no confidence in the local ruling class’ capacity to survive in its home patch). Those responses only exaggerate the objective crisis – corruption rots the State’s capacity to act, and taking cash out of the country wrecks the balance of payments and undermines the value of the currency. Furthermore, such responses strip back the foggy rhetoric of the ‘national interest’ and reveal the purely parasitical function of the ruling class, subordinating the material condition of the majority to private gain. It reveals also the existence of a world order – the capital and capitalists flee to their secure refuges in the MDCs, abandoning their temporary home in the LDCs.

The thin ideological justification of the local ruling class role disappears, and while this is not vital so far as the mass of the population in the LDCs is concerned, it pushes the middle classes into disaffection. Then only physical power – and the elimination of all right to criticise within the ruling class – holds the social order together. This is part of the explanation for the sustained collapse of parliamentary institutions, the ‘rule of law’ and the ‘free press’ in most of the LDCs, whether through military means in Brazil, Chile and Argentina, or through the establishment of civilian dictatorships in the Philippines, South Korea, Pakistan and Mrs Gandhi’s India. On a milder scale, the same trends are apparent in the MDCs also, although there ideological control is more important, and therefore the need to create suitable targets to divert attention from the local ruling class – foreigners, imports, minorities and immigrants.

Physical power requires a sustained expansion in military and police spending (which exaggerates the diversion of investment into unproductive activities and sets further obstacles to resuming growth in output and jobs). In 1975, world defence spending was running at $345 billion per year (by comparison, a ten year plan for the world steel industry, 1976-86, was to cost the ‘gigantic’ sum of $220 billion for the whole decade) or not much short of $40 million per hour (figures which make the debt figures mentioned earlier rather trivial!). It took half the research and development spending of the world (three times world spending on medical research) and employed 40 per cent of all scientific and engineering manpower in the world. But the fastest growing sector of world military spending is in the LDCs. They increased their share of the world arms trade from 6 per cent in 1954 to 22 per cent in 1975. Currently, LDC weapon imports are increasing about twice as fast as their gross national products. In absolute terms, the main spenders are the richer LDCs, especially the oil producers; the Middle East currently spends $135 per head of the population on the means to kill. Nigeria increased its military forces ten times over from 1967. The poorer non-oil producing LDCs are not far behind in the race. India’s defence spending, increasing by 16 per cent per year in the 1960s, currently takes over a third of the national budget. Egypt increased its military spending three and a half times over between 1967 and 1974. The figures for police spending show comparable increases.

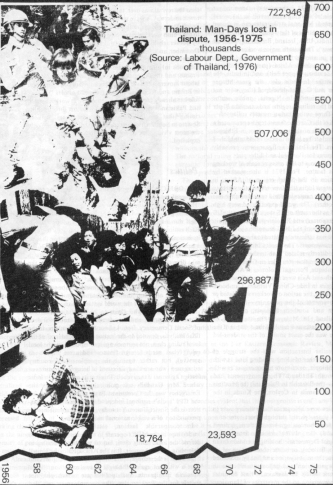

The increase in the ruling class capacity to intimidate is not a response to an illusory threat. Not only are the rhythms of revolt becoming synchronized in the world system, so that all ruling orders come under pressure simultaneously (and are unable therefore to help each other out to the same extent), but also they are reaching a scale that wrecks local control. As a point of entry to the question of working class revolt, the graph of Thai strike statistics can be used as an illustration (cf. box). The small – in Thai terms – upswing of 1966 came just after the explosions in Indonesia and Brazil (both terminating in savage military coups). The slightly larger upturn of 1968-69 – which produced the first instability in the Thai military order – coincided with major movements in India and Pakistan [5], culminating in military repression in eastern India in 1971 and the break up of Pakistan (and the creation of Bangladesh). There were also major confrontations in those years in Ceylon (1971), Mexico, Trinidad, Guatemala and others, but staggered in different years.

|

The next upturn, in 1973-74, is the most synchronized yet seen, and on a scale of working class revolt in the world hitherto unprecedented. National strike rates ran at record levels in most of the countries of the world (but particularly in Italy, Australia, India, USA, Ireland, Britain, Japan, West Germany and Norway). There were major worker revolts in Chile (culminating in another barbarous coup), Burma, Malaysia, Jamaica, Southern Africa (particularly South Africa and on the Zambian copper belt), and in India, the gigantic railways strike. In India also, the great hunger campaigns in Bihar and Gujerat developed (they were not specifically worker actions). In Nigeria, public sector workers intimidated the military regime and exacted a 30 per cent pay increase. Three authoritarian regimes collapsed – in Portugal, the end of the Caetano fascist regime promoted a very rapid radicalization of the working class; in Ethiopia and Thailand, general strikes led to the end of old established authoritarian orders. The Thai strike figures were probably exceeded by the figures for Portugal and Ethiopia.

The other side of the coin to this massive scale of working class opposition is famine. For 1974 is also marked by widespread starvation in the Sahel region of Africa, in Bangladesh and eastern India (the famines and the working class revolt had the same causes in world capitalism; the one did not cause the other). The world experienced very high grain prices in 1974 as the result of US stock policies (the US is the major grain exporter) and Russian purchases of grain in response to the failure of the 1973 harvest. [6]

The worker revolt was intimately related to the rebellion of other classes and movements. The events in Portgual and South Africa were directly related both to the world crisis and to the national liberation struggles in Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique, Portugal’s colonies in Africa that time. Events in south-east Asia were much less influenced by the liberation struggles in Indo-China (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos). Furthermore, the action of workers stimulated or coincided with movements of the peasantry – in southern Portugal, northern and southern Ethiopia, central and north-eastern Thailand. In Malaysia, the starvation of rubber-tappers on the estates as a result of the collapse of the world rubber price was the main source of the student-led riots of mid-1974.

There was a similar interaction with the struggle of national minorities, whether of a long-standing kind as with the Eritreans in Ethiopia, or of more recent origin, as with the Muslims of south Thailand. Those movements had parallels elsewhere – the Baluchis in Pakistan [7], the Muslims in south Philippines, Tamils in Ceylon, the Kurds in the Middle East etc.

Most ruling classes were able to stabilize their power in the following two years, partly through short term concessions (financed from borrowing abroad), through direct repression (Thailand, Oct. 1976), military intervention (Ethiopia) or a Social Democratic holding operation (as in Portugal, and also Britain), or some combination of all methods. In Nigeria, the military tried and finally succeeded in ‘trade union reorganisation’ and imposing a nine month wage freeze (in June 1976). In Jamaica, Prime Minister Manley’s sudden conversion to the mysteries of ‘Jamaican Socialism’ was a cover for the introduction of the Gun Court, and Industrial Relations Act to break shop floor militancy, and, this year, a wages freeze. Mrs Gandhi carried out an almost identical exercise in India under the cover of the June 1975 Emergency.

The ruling classes gambled on their short term prospects in the hope that the world system would return to expansion before lenders and working classes foreclosed. In late 1975, it seemed they had been vindicated by the revival of the US economy. But it was no more than a brief restocking boom that ended abruptly. By the time it was clear the revival was over, there was already another wave of revolt underway, a wave we are currently in the midst of. The Polish State, endeavouring to offload its external burdens on to the Polish working class, was, a year ago, heavily defeated by worker rebellion. The Sri Lanka general strike followed in December, and almost immediately afterwards, the events in Egypt this January. Since then there have been important collisions in Holland, Belgium, a one day general strike in France, and the threat of a mass stoppage in Sweden. The labour movements have moved back towards confrontation in Britain and Australia. In India, the end of Mrs Gandhi’s rule has already produced a major upsurge in worker battles, and Pakistan is currently wracked by almost three months rioting (that has included ten one day general strikes). Soweto in South Africa and the events that followed are only the most vivid index of the return to battle of the world’s exploited.

THE OBJECTIVE structure of the world is impelling revolt and confounding the supposed differences between the ‘Third World’ and the other two. The inhabitants of each national ghetto fight to escape the logic of a world system, itself dominated by the leading imperialist ruling classes. Each national order is robbed of the basic capacity to guide its national patch, robbed of any political alternative that, at a bare minimum, will stabilize the material conditions of the majority inside the patch. The majority of the world’s States are, despite rhetorical pretensions, reduced closer to the status of South Africa’s Bantustans.

Yet the system remains intact and with considerable resources for survival. Despite the courage of the rebels, the movements of revolt cannot spontaneously formulate a political alternative for the world system which is what is at stake. The people who claim to be revolutionaries, the Communist parties, and the reformists (the sundry varieties of Social Democracy, from Labour to Peronism) are, in the final analysis, devoted to the ‘national independence’ of the local ruling class, not so much against imperialism (the local ruling class needs foreign finance and arms imports to survive), but rather against the people of the country concerned (who are always accused of being the creatures of foreign agitators if they rebel). This is at its most vivid in India where Mrs Gandhi’s sole political ally all through the Emergency was the Communist Party of India. Indeed, for the CPI ‘India’s national independence’ means subordination to the Soviet Union. Yet today, world revolution is the pre-condition of a viable national independence.

In comparable fashion, established trade union leaderships in the MDCs operate in the crisis, not simply to defend the local ruling class, but to take the leadership in defending national power. It is the AFL-CIO in the United States that is the strongest pressure group to ban imports and start a witchhunt against the eight to twelve million ‘illegal’ Mexican immigrants. Such politics are catastrophic not merely for the working class (the unemployment resulting from contracting the US market) and its American section (unemployment results there through reducing imports), but also for world capitalism. The only gainers are the local ruling class in their relative power, and even that is a temporary gain.

In the collisions of 1974, the potential of workers power was clear, but there was no political leadership capable of beginning the task of conquering world power. The lack of a workers’ international to unite both the diverse oppositions to the status quo (peasants, national minorities) and the different national sections of the working class left a political vacuum ultimately filled by the worst barbarities of the ruling class. Yet even without revolt, the system is set upon a course of increasing barbarization. It is that process which promises that 1974 is only a prelude to much more spectacular collisions in the future, and that the task of building the political alternative will become increasingly realized.

In conclusion then, the impact of the crisis has been to force the appearance of a class structure appropriate to the centralized world economic system. On the one hand, a world ruling class, riven by increasing fierce rivalries that can produce war, but no less bound by an increasing degree of collaboration, even for those ruling classes governing the oppressed nations of the world; on the other, a world working class.

In the nineteenth century, the size of firm and the capital intensity of production permitted a drop in the profit rate to be restored through bankruptcies (and mass unemployment). Already by the 1930s, that recipe did not work, despite mass unemployment; only the second World War restored the profit rate. Now, after an unprecedented quarter of a century’s growth, the system is returning to stagnation. The impossibility of permitting the bankruptcy of major sections of national capital (which would disastrously weaken the capacity of the national ruling class to compete with its foreign rivals in the future) as well as the political impossibility of driving unemployment high enough to achieve a decisive shift from consumption to profits, paralyses all tendencies for the profit rate to make a sustained recovery. The result is stagnation with relatively high rates of inflation which increase rapidly with any small increase in activity. But stagnation imposes steady attrition in place of sudden collapse (which does not rule out sudden collapse for particular national units). The attrition compels a continuous reordering of national institutions to unify the power of the ruling class, a reordering that conceals the lack of any political alternative for the ruling class other than cutting living standards and repression.

The changes undermine the possibility of a national reformist strategy, whether as presented by existing ruling classes (embodied in national development plans) or by the conventional opposition (Communist parties, whether pro-Russian or pro-Chinese). The assumption of automatic industrialization, of economic development, which underpinned the confidence of the ruling classes of the LDCs, and was part of the justification of the ruling classes in the MDCs, comes to an end. The idea that, for every national patch, there exists a pattern of domestic production that will guarantee national power, full employment and tolerable incomes, and is achievable within national boundaries without the destruction of imperialism also comes to an end. The national ruling class stands revealed as no more than a parasitic formation, obstructing the development of the world’s productive forces.

Thus, a set of conditions emerge which are mutually reinforcing in the task of world revolution. Ruling classes impose an intolerable degree of suffering upon the mass of the population in defence of their privileged position, when their own morale is low and they are divided. Increasingly, the logic of the system forces the synchronization of the fight back. Objectively, the conditions for breaking the system and creating the old Communist International target, an international workers’ republic, have not been so promising for forty years. But the international ‘vacuum on the Left’ is still a fearful obstacle. Overcoming it is now the most urgent task.

1. All money measures except where specified are in US dollars. ‘Billion’ means a thousand million.

2. On the Polish case, See Chris Harman, Poland, the Crisis of State Capitalism, I and II, International Socialism 93 and 94, 1976-77.

3. Detailed in the Far Eastern Economic Review, May 13 1977, pp.40-42.

4. Described in Michael Kidron’s Imperialism: the Highest Stage but One, and International Capitalism, reprinted in Capitalism and Theory, London, 1974, pp.124-158.

5. See my India, I and II, International Socialism 52 and 53, 1972.

6. ‘It becomes evident that the bourgeoisie is unfit any longer to be the ruling class in society and to impose its conditions of existence upon society as an overriding law. It is unfit to rule because it is incompetent to assure an existence to its slave within slavery, because it cannot help letting him sink into a state that it has to feed him, instead of being fed by him. Society can no longer live under this bourgeoisie; in other words, its existence is no longer compatible with society’ – Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, in Karl Marx, Selected Works, London, n.d., I, p.218.

7. The 1970-71 events in Pakistan were generated by the same interaction between worker and peasant movements in East and West Pakistan and the national struggle of the Bengalis of the East – cf. my Bangladesh, International Socialism 50, Jan-Mar 1972.

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 16.1.2008