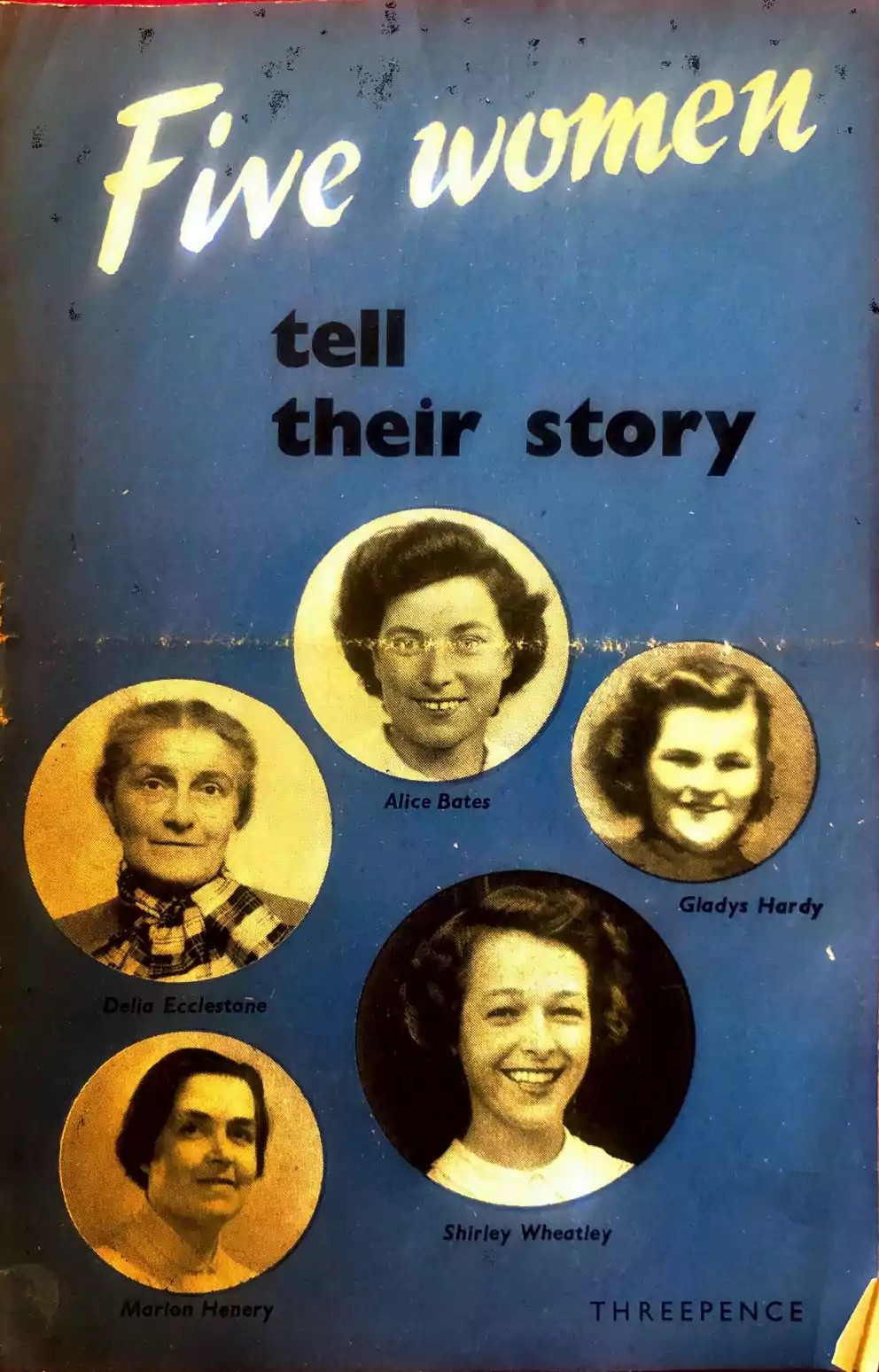

This is the story of five women, and they have written it themselves. They are ordinary women, mothers and workers like you, reading this pamphlet. Like you their deepest desire is to make sure their children have a chance to grow up to a peaceful, happy life.

None of us want the days of poverty and unemployment that our parents lived through to return. None of us want our children to go through another war. We passionately want a different life. We wanted it in 1945, when the Second World War ended, and to many it seemed then, when the Labour Government was returned to power, much nearer than had ever seemed possible.

But the post-war hopes have not come true. We know from the way we live, month by month, that it's harder now to manage than it was. There's poverty in many homes today; there's unemployment in some. The future for the children hasn't opened out as we had a right to expect. The shadow of war is still there.

So we are faced with a burning question. Is it to be the same all over again for our children? Must our dreams always remain dreams?

This is the question that in one way or another these five women faced. Let them explain for themselves.

To build a new world

Here is Alice Bates of Manchester. She is thirty-two years old, and has three fine children, a boy of nine, and two girls of seven and two years old. Her husband is an engineering worker in one of the biggest factories in the district.

“I was the youngest of five children, and as far back as I can remember there was always trouble in our house because there wasn't enough money. My father was a coal carter, but I can scarcely remember his working. We always seemed to be having visitors from ‘the sick’, ‘the unemployed,’ ‘the board of Guardians’. There was a continual charity atmosphere about the money we received.

I was fortunate enough to go to school till I was fifteen, and was one of a very small group in a very large school who received free uniform and free dinners, and wasn't it obvious to the rest of the class!

When I start to write so much comes back. The rows when my sister, who was a clothing presser, brought home her many ‘short weeks.’ The rows when my brother found his suit was still in pawn at the week-end. The time when I had to stay off school because my gym slip was pawned, and the unwritten rule that you had fish and chips if you were a wage-earner, and only chips if you weren't.

I longed to be a teacher, but my mother simply couldn't wait any longer than fifteen for my wages, and I went out to office work.

At first I was so ashamed of my family's poverty that I never told my work-mates anything about my family, and never asked them home. But after a while I felt a great sense of injustice that while thousands of families like ours were just existing from week to week, hundreds of others (according to society gossip) were able to spend more on one meal or one coat than we had for a whole week.

At this time my love of dancing and social life brought me into contact with people of my own age who were members of the Labour League of Youth and the Young Communist League. For the first time I was able to talk freely to them of my family and my feeling of injustice. From then on I began to study the answers offered by the various political parties to the plight of families like outs.

In 1942 I joined the Communist Party, because I felt that here was a party that not only understood how families like mine had to live, but saw what must be done to alter things — not just in the dim and distant future, but practical things that could be done almost from week to week.

And that was only the beginning. Since joining the Party I have learnt that things don't ‘just happen’, leaving us standing by helpless. I have realised that ordinary people working together are a force which can build a completely different world.

Now that I have three children of my own I want to use the knowledge and confidence I have found to be a builder of that new world for my children, where they will not know poverty, insecurity and wars.”

A way of life to choose

Here is a different story from Delia Ecclestone of Sheffield. She is fifty years old, the mother of three boys, the eldest just starting his national service. Her husband is the vicar of Holy Trinity, Darnall, a big working-class parish.

“Looking back to my childhood, the youngest of ten in a very Tory family, it may seem a strange place to start the makings of a Communist. But it was just in this setting, and because of it, that I began to question and puzzle over so many things my family took for granted, and to come down on the other side.

Going out to work, and living in lodgings in Camberwell and later West Cumberland during the years of unemployment, getting to know ordinary people, their lives and problems under the means test, made me take sides, and I knew the only side I could take was with the workers, the dispossessed, whether in England or abroad; and I knew that this contradicted nothing in Christianity – Mary’s great song that God had pulled down the mighty, filled the hungry with good things, sent the rich empty away. And anyhow Christ was a good working man, a carpenter, and he knew in an occupied country what extreme poverty meant.

So the years came of Manchuria, Abyssinia, Spain and Munich and at each turn we – for I was now married to a man of the working class with far greater knowledge of this whole struggle in the past – we knew we must come down on the side of the people. Finally it was the attitude of Attlee and the others over Czechoslovakia in February, 1948, that opened our eyes, and we saw that the leaders of the Labour Party had come down on the wrong side when tested, and we must go with the people, however much we did not see everything clearly at the time.

So we joined the Communist Party and became part of the local branch working with the other comrades, learning from them, thinking and reading and talking things out and doing things together. Now, five years later, there are several members of our church in the Party, some of the keenest workers for peace and Socialism in this end of Sheffield. Do you think that sounds impossible? But of course I'm not meaning people who just ‘go to church’. We believe the Christian religion has to do with every scrap of a person's life, so of course politics, nursery schools, the health of children, ceasefire in Korea and the topping of napalm being used for misery against the people — all this is part of doing God's will on earth.

There is nothing odd or irreligious to us about coming out of church with a hundred or so other Christians, and then taking a ten-minute tram ride to sell Daily Workers with other comrades. I do this because I want more and more people to know the truth.

Was there anything contradictory between Christianity and Communism when three of our church members, two belonging to the Party and one not, went straight from the service in church to the local Labour hall to speak with our Member of Parliament on the question of rising prices and peace in Korea? They did this as part of their Christianity.

On a table in the church there are Chinese magazines about their new life. Christ said that he came so that men everywhere should have more abundant life. So there are magazines about Poland, about children in the British colonies, a survey of the lives of old age pensioners in Sheffield. As Christians we must be concerned with the world and the people in it. It is the people that matter. They must not be made to work for the profit of others. As Communists we want to stop this too.

We all have to make a decision. On the one hand there are rearmament, rising prices, conquest in the colonies. On the other, the Communist Party struggling for a fuller, better life for all, for peace and health and culture, without distinction of colour, creed or race — a way of life as against a way of death. You must choose life.”

For her children's birthright

Then there is Gladys Hardy of Oldham. She is thirty years old, and has two boys and a little girl. Her husband is a vehicle builder, and they live on a council housing estate.

“Let me tell you a little of my childhood. I was the eldest of a family of seven, living in Oldham, a town noted for its cotton industry.

As far back as I can remember, my father, a labourer, never had full employment. I can remember him, day after day, walking the streets of the town looking for work, but always coming home tired and weary. Never any work. This was in the 1930s and of course meant that he was on the means test, which meant us children having to have free milk, free dinners and free clogs. All this made me very self-conscious, because I hated clogs, the more so as I was the only girl in the class at school who wore them.

I can remember the time when I was dropped from the netball team because I had no pumps, and only allowed to go back because someone took pity on me and gave me a pair. Anyone who has had to wear clothes handed on to them will know what it feels like. It was always at the back of my mind that everyone knew these weren't my clothes, but that such and such a person had given them to me.

The only time we had new clothes was at Whitsuntide when my mother went heavily into debt for them. The boys suits went into the pawn shop every Monday morning, and came out again on Friday ready for us to go to Sunday school in.

I passed exams to go to high school, but wasn't allowed to go because it would mean going to school till I was fifteen. I left school at fourteen, and went to work in a cotton mill, because the wages there were higher. I remember my father crying the day I fetched home my first week's wages, 17/6. He couldn't get work but his daughter could. The answer of course was that I was cheap labour, although I didn't know it then.

All these things stick in my mind, and I used to say even then ‘If ever I have any children something will have to be different’.

Up to the time of getting married I knew nothing of politics, only that after all my parents had gone through and suffered they voted Tory and still do. They say ‘My father and mother were Tory so we'll keep it up’.

As for Communists! In the early part of my life I detested this word for I had been led to believe by the people round, the Press, the radio, that they were awful people, always making trouble, that they were an ignorant and illiterate class of people. Now I know that it was I who was ignorant of life.

Then my husband joined the Communist Party. I was disgusted with him, thought it an awful thing he had done. He didn't do much at first. That meant that someone called at the house with membership stamps for him, and of course when they sat down they used to be ‘nattering on’. I called it, for an hour or more. I know now that when Communists want anything they'll stick at it until they get it, and they wanted my husband to go to meetings and classes.

I used to be knitting and listening to their conversation against my will at first. Then I began to realise that they were fighting for the very things I wanted for my children. They had children the same as me, and they wanted them to live in peace as I did.

One evening one of the men's wives called to take me to a women's group meeting. I must confess I would never have gone by myself. After going a few times I knew that here were people who would help me to get what I wanted, not only for my children but for all children, and I joined the Party.

I have two fine sons and a lovely little daughter. They are part of my life, and I shall go on working in the Party for them until they have all the things I missed, a good education, security, enough food and clothes to keep them healthy, somewhere decent to live and play, and above all, peace. I don’t want my son to go in the prime of his life to kill some other mother’s son, or maybe get killed himself. I don’t think I’m selfish wanting these things for my children. It’s only their birthright.”

A woman set free

Here is Shirley Wheatley of Leeds. She is a clothing worker, twenty seven years old, and has one little girl. Her husband is an engineering worker, a shop steward, and they live in a working-class part of the city in a narrow street of back-to-back houses.

“Nine years ago I decided to marry a man who was interested in politics. I was an ordinary working-class girl of average intelligence, with no knowledge of politics at all. I was religious, and believed everything that was said on the radio and in the papers.

The man I married was just the opposite. He had Communist ideas, but was not a member of any party. My main worry and aim in life was to get a home of our own and have a family. Well, we got our home and a child and these constituted our life.

But when we had got our home and child we found that we could not afford to live the life we wanted. We could not afford to have any more children, and in order to feed and clothe ourselves properly I had to go out to work. This made my husband become more interested in politics, and eventually he joined the Communist Party.

l shall never forget the day he came home and told me he had joined. I was filled with the most terrible fear, and so that he could not see how upset I was I got him to tell me how he had joined, and as he was talking my fears subsided.

But from that day our way of life altered. My husband started to go to party meetings, and then he went out selling Daily Workers, and then going to trade union meetings, until it seemed as if he was always going out and I was left at home.

Naturally I began to resent this, and tried to put a stop to it. I tried to make him choose between me and the Party, and told him that if he continued working for the Party we would eventually part. This made him see that in order to remain in the Party he must get me interested in it as well, and gradually, so that I did not even realise what was happening, he started to draw me in.

He first started taking me to meetings and to socials, and got me mixing with other Communist Party members, encouraged me to go out more, until I finally joined too. But I found that once I had joined, just believing in the principles of the Communist Party was not enough, and that to answer other people's arguments I needed knowledge.

Well, this became my stumbling block, because I thought it was impossible for me to study and learn more. I tried to read a book on political economy, and threw it down in despair, and told my husband I would never be able to read Communist books.

So he started buying me political novels to read, and I enjoyed reading those, and gained a little more knowledge. But this was not enough — as I had to rely on him to answer all the questions put to me, and my life seemed to be made up of continuous discussions with everyone I met, I began to wonder if it was really worth it.

Then my husband got me to a Communist Party school. I did not want to go, but seemed to be pushed into it. This school altered my whole outlook. Not only did I find I could take in knowledge, but that I wanted to, and that I could read and understand things like political economy.

Now I could look back and see what a narrow family life I had led, and the full meaning of what the oppressed working class meant. I had been oppressed and imprisoned, and suddenly I was set free.

Can you imagine how a bird in a cage feels, after it has been battering about inside a cage and wearing itself out, when it is suddenly set free? It is so wonderful that you want to tell everyone else in order that they can become free. That is when you realise why the Communist Party is different from any other political party, that is not just a party wanting to gain power, but that it means what it says, it will help to free the oppressed peoples of the world.”

“What's for us” depends on us

Last comes Marion Henery. She is forty-three years old, and has two boys, seventeen and sixteen years old, and a little girl of seven. Her husband is a miner, and they live in the village of Auchinloch, near Lenzie in Scotland.

“My father was one of the early Socialists, a member of the Clarion Club. One of my earliest recollections was of my brother refusing to fight in the 1914-18 war, of my mother's anxieties and the heartbreak every time a younger brother returned from army leave.

I was taught the ideas of Socialism in the Socialist Sunday School. I remember arguing with my colleagues there about the 1929 Labour Government. I agreed with the criticism of the Communists about that Government.

But more important, I was impressed by the fact that to the Communists Socialism wasn't something for the dim and distant future, but a possibility in our lifetime in this country. When I began to work with the Communists I was won over by their sincerity, their capabilities, and the equality and comradeship in their relations with me and each other.

My personal story is linked with the story of those who were lucky enough to join the Party and learn the why and wherefore of the troubles that were to crowd in on us in the Hungry Thirties. There was growing hardship, but there was growing struggle and organisation.

I marched with lasses of sixteen to sixty from all the main cities of England and Scotland, from Burnley to London. The Communist Party did more than organise the unemployed. It raised the banner of hope.

Very early in our married life, our two sons just babies, we left derelict Lanarkshire. Joe had 3s. 4d. in his pocket. We found tree-lined streets in Welwyn Garden City, and low wages and high rents.

With the Second World War Joe was conscripted for the pits and we went back to Scotland. Finally we got a house. Then the war was over and hopes high. We threw ourselves wholeheartedly into the fight to return the Labour Government. Our daughter Morag was born.

Now in such a short space of time the Tories in power have undone most of what was done by that Labour Government.

Are we to repeat the painful experience of the thirties—growing unemployment, growing war preparations? When I think of the fate of our boys in the Malayan jungles, of what they went through in Korea, of the massacre of the valiant Korean people, I think of my two sons Joseph and Robert, at present studying for their higher certificate. The thought of them conscripted to go to fight fills me with horror.

I've often heard women saying ‘What's for you won't go past you’. What's for me and my boys, what's for you and yours, is what we work for. What's for us will depend on how we build the only real fighting leadership of the working class, the Communist Party.

After twenty-three years in the Party my faith and ardour for it are stronger than ever. You'll find some of the very best people in this party. You'll find a world of new ideas opened up to you. You'll find that the Party brings out the best in you. This big family that we join unites us in a great common bond, in work for a new life under Socialism, a guarantee of an end to wars, and plenty for all.”

These five women have found in the Communist Party an answer to the question, “is it to be the same all over again for us and our children?”

They want the things that you want — peace with the shadow of war banished for ever. They want a better chance in life for their kiddies than they have had, and an end to the worry of trying to make ends meet. They want our country to belong to us. They want a different life: a life of hope and happiness and laughter. They've joined the Communist Party to help work for these things.

For we can change Britain. The Communist Party has a programme, The British Road to Socialism, which shows how we can start to make our country a splendid place for ordinary people.

Working together we can make a new life where prices come down and wages go up. where instead of making guns and bombs and tanks we shall build all the things we need, houses, schools and hospitals. For the women who want to work outside the home there will be all sorts of interesting jobs to train for, and with equal pay. Every child will have the same chance in life. No more scholarship exams at eleven. No more long holidays in the back streets and bombed sites, for the mansions and palaces that are scattered all over Britain we shall turn into holiday centres for the workers and their children.

It's to work for this new world that these women have joined the Communist Party. There ten thousand more like them. Very often women who agree with what the Communist Party says feel that they themselves could not join it. It seems to them that it would be too difficult, that it would take too much time, that they would have to do things they have never done in their lives before.

These stories show how women who have come into the Communist Party found that they gained help and understanding of a new kind.

Their family life is enriched. They have made new friends, new interests, and binding them all together is a wonderful vision of the future. They know now where they are going. They know that by working in the Communist Party and with the Communist Party among millions of other women, the new world will be won in the only way possible, not by wishing for it, but by working for it. The more of us who work together in the Communist Party, the more certain we are that this new life will be built, not in our grandchildren's time, but very soon in our time.

This pamphlet will not answer all your questions. But we hope you will discuss it in your family, among your neighbours and friends, and decide to take your place with us, in the Communist Party as builders of the new Britain.