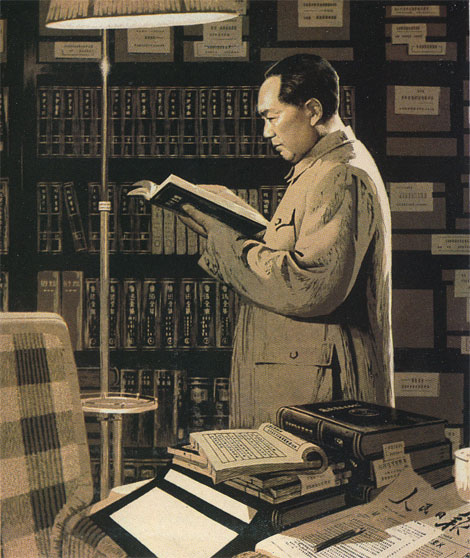

Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung

Reading Notes On The Soviet Text

Political Economy

1961-62

[SOURCE: Long Live Mao Zedong Thought, a Red Guard Publication.]

Part I.

Chapters 20-23

1. From Capitalism to Socialism

The text says on pages 327-28 that socialism will “inevitably” supersede capitalism and moreover will do so by “revolutionary means.” In the imperialist period clashes between the productive forces and the production relations have become sharper than ever. The proletarian socialist revolution is an “objective necessity.” Such statements are quite satisfactory and should be made this way. “Objective necessity” is quite all right and is agreeable to people. To call the revolution an objective necessity simply means that the direction it takes does not hinge on the intentions of individuals. Like it or not, come it will.

The text says on pages 327-28 that socialism will “inevitably” supersede capitalism and moreover will do so by “revolutionary means.” In the imperialist period clashes between the productive forces and the production relations have become sharper than ever. The proletarian socialist revolution is an “objective necessity.” Such statements are quite satisfactory and should be made this way. “Objective necessity” is quite all right and is agreeable to people. To call the revolution an objective necessity simply means that the direction it takes does not hinge on the intentions of individuals. Like it or not, come it will.

The proletariat will “organize all working people around itself for the purpose of eliminating capitalism.” (p. 327) Correct. But at this point one should go on to raise the question of the seizure of power. “The proletarian revolution cannot hope to come upon ready-made socialist economic forms.” “Components of a socialist economy cannot mature inside of a capitalist economy based on private ownership.” (p. 328) Indeed, not only can they not “mature”; they cannot be born. In capitalist societies a cooperative or state-run economy can not even be brought into being, to say nothing of maturing. This is our main difference with the revisionists, who claim that in capitalist societies such things as municipal public enterprises are actually socialist elements, and argue that capitalism may peacefully grow over to socialism. This is a serious distortion of Marxism.

2. The Transition Period

The book says, “The transition period begins with the establishment of proletarian political power and ends with the fulfilment of the responsibility of the socialist revolution — the founding of socialism, communism’s first stage.” (p. 328) One must study very carefully what stages, in the final analysis, are included in the transition period. Is only the transition from capitalism to socialism included, or the transition from socialism to communism as well?

Here Marx is cited: from capitalism to communism there is a “period of revolutionary transformation.” We are presently in such a period. Within a certain number of years our people’s communes will have to carry through the transformation from ownership by the basic team to ownership by the basic commune,[1] and then into ownership by the whole people.[2] The transformation to basic commune ownership already carried out by the people’s communes remains collective ownership [and is not yet ownership by the whole people: Note in brackets inserted by translator for clarity].

In the transition period “all social relations must be fundamentally transformed.” This proposition is correct in principle. All social relations includes in its meaning the production relations and the superstructure — economics, politics, ideology and culture, etc.

In the transition period we must “enable the productive forces to gain the development they need to guarantee the victory of socialism.” For China, broadly speaking, I would say we need 100-200 million tons of steel per year at the least. Up to this year our main accomplishment has been to clear the way for the development of the productive forces. The development of the productive forces of China’s socialism has barely begun. Having gone through the Great Leap Forward of 1958-1959, we can look to 1960 as a year promising great development of production.

3. Universal and Particular Characteristics of the Proletarian Revolution in Various Countries

The book says, the October Revolution “planted the standard,” and that every country “has its own particular forms and concrete methods for constructing socialism.” This proposition is sound. In 1848 there was a Communist Manifesto. One hundred and ten years later there was another Communist Manifesto, namely the Moscow Declaration made in 1957 by various communist parties. This declaration addressed itself to the integration of universal laws and concrete particulars.

To acknowledge the standard of the October Revolution is to acknowledge that the “basic content” of the proletarian revolution of any country is the same. Precisely here we stand opposed to the revisionists.

Why was it that the revolution succeeded first not in the nations of the West with a high level of capitalist productivity and a numerous proletariat, but rather in the nations of the East, Russia and China for example, where the level of capitalist productivity was comparatively low and the proletariat comparatively small? This question awaits study.

Why did the proletariat win its first victory in Russia? The text says because “all the contradictions of imperialism came together in Russia.” The history of revolution suggests that the focal point of the revolution has been shifting from West to East. At the end of the eighteenth century the focal point was in France, which became the center of the political life of the world. In the mid-nineteenth century the focal point shifted to Germany, where the proletariat stepped onto the political stage, giving birth to Marxism. In the early years of the twentieth century the focal point shifted to Russia, giving birth to Leninism. Without this development of Marxism there would have been no victory for the Russian Revolution. By the mid-twentieth century the focal point of world revolution had shifted to China. Needless to say, the focal point is bound to shift again in the future.

Another reason for the victory of the Russian Revolution was that broad masses of the peasantry served as an allied force of the revolution. The text says, “The Russian proletariat formed an alliance with the poor [Only in the 1969 text: Note by translator.] peasants.” (p. 328-29, 1967 edition) Among the peasants there are several strata, and the poor peasant is the one the proletariat relied on. When a revolution begins the middle peasants always waver; they want to look things over and see whether the revolution has any strength, whether it can maintain itself, whether it will have advantages to offer. But the middle peasant will not shift over to the side of the proletariat until he has a comparatively clear picture. That is how the October Revolution was. And that is how it was for our own land reform, cooperatives, and people’s communes.[3]

Ideologically, politically, and organizationally the Bolshevik-Menshevik split prepared the way for the victory of the October Revolution. And without the Bolsheviks’ struggle against the Mensheviks and the revisionism of the Second International, the October Revolution could never have triumphed. Leninism was born and developed in the struggle against all forms of revisionism and opportunism. And without Leninism there would have been no victory for the Russian Revolution.

The book says, “Proletarian revolution first succeeded in Russia, and prerevolutionary Russia had a level of capitalist development sufficient to enable the revolution to succeed.” The victory of the proletarian revolution may not have to come in a country with a high level of capitalist development. The book is quite correct to quote Lenin. Down to the present time, of the countries where socialist revolution has succeeded only East Germany and Czechoslovakia had a comparatively high level of capitalism; elsewhere the level was comparatively low. And revolution has not broken out in any of the Western nations with a comparatively high level of development. Lenin had said, “The revolution first breaks out in the weak link of the imperialist world.” At the time of the October Revolution Russia was such a weak link. The same was true for China after the October Revolution. Both Russia and China had a relatively numerous proletariat and a vast peasantry, oppressed and suffering. And both were large states. . . . [Ellipsis in original: Note by translator.] But in these respects India was much the same. The question is, why could not India consummate a revolution by breaking imperialism’s weak link as Lenin and Stalin had described? Because India was an English colony, a colony belonging to a single imperialist state. Herein lies the difference between India and China. China was a semicolony under several imperialist governments. The Indian Communist Party did not take an active part in its country’s bourgeois democratic revolution and did not make it possible for the Indian proletariat to assume the leadership of the democratic revolution. Nor, after independence, did the Indian Communist Party persevere in the cause of the independence of the Indian proletariat.

The historical experience of China and Russia proves that to win the revolution having a mature party is a most important condition. In Russia the Bolsheviks took an active part in the democratic revolution and proposed a program for the 1905 revolution distinct from that of the bourgeoisie. It was a program that aimed to solve not only the question of overthrowing the tsar, but also the question of how to wrest leadership from the Constitutional Democratic Party in the struggle to overthrow the tsar.

At the time of the 1911 revolution China still had no communist party. After it was founded in 1921, the Chinese Communist Party immediately and energetically joined the democratic revolution and stood at its forefront. The golden age of China’s bourgeoisie, when their revolution had great vitality, was during the years 1905-1917. After the 1911 revolution the Nationalist Party was already declining. And by 1924 they had no alternative but to turn to the Communist Party before they could make further headway. The proletariat had superseded the bourgeoisie. The proletarian political party superseded the bourgeois political party as the leader of the democratic revolution. We have often said that in 1927 the Chinese Communist Party had not yet reached its maturity. Primarily this means that our party, during its years of alliance with the bourgeoisie, failed to see the possibility of the bourgeoisie betraying the revolution and, indeed, was utterly unprepared for it.

Here (p. 331) the text goes on to express the view that the reason why countries dominated by precapitalist economic forms could carry through a socialist revolution was because of assistance from advanced socialist countries. This is an incomplete way of putting the matter. After the democratic revolution succeeded in China we were able to take the path of socialism mainly because we overthrew the rule of imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucratic capitalism. The internal factors were the main ones. While the assistance we received from successful socialist countries was an important condition, it was not one which could settle the question of whether or not we could take the road of socialism, but only one which could influence our rate of advance after we had taken the road. With aid we could advance more quickly, without it less so. What we mean by assistance includes, in addition to economic aid, our studious application of the positive and negative experiences of both the successes and the failures of the assisting country.

4. The Question of “Peaceful Transition”

The book says on page 330, “In certain capitalist countries and former colonial countries, for the working class to take political power through peaceful parliamentary means is a practical possibility.” Tell me, which are these “certain countries”? The main capitalist countries of Europe and North America are armed to the teeth. Do you expect them to allow you to take power peacefully? The communist party and the revolutionary forces of every country must ready both hands, one for winning victory peacefully, one for taking power with violence. Neither may be dispensed with. It is essential to realize that, considering the general trend of things, the bourgeoisie has no intention of relinquishing its political power. They will put up a fight for it, and if their very life should be at stake, why should they not resort to force? In the October Revolution as in our own, both hands were ready. Before July 1917 Lenin did consider using peaceful methods to win the victory, but the July incident demonstrated that it would no longer be possible to transfer power to the proletariat peacefully. And not until he had reversed himself and carried out three months’ military preparation did he win the victory of the October Revolution. After the proletariat had seized political power in the course of the October Revolution Lenin remained inclined toward peaceful methods, using “redemption” to eliminate capitalism and put the socialist transformation into effect. But the bourgeoisie in collusion with fourteen imperialist powers launched counter-revolutionary armed up-risings and interventions. And so before the victory of the October Revolution could be consolidated, three years of armed struggle had to be waged under the leadership of the Russian party.

5. From the Democratic Revolution to the Socialist Revolution — Several Problems

At the end of page 330 the text takes up the transformation of the democratic revolution into the socialist revolution but does not clearly explain how the transformation is effected. The October Revolution was a socialist revolution which concomitantly fulfilled tasks left over from the bourgeois democratic revolution. Immediately after the victory of the October Revolution the nationalization of land was proclaimed. But bringing the democratic revolution to a conclusion on the land question was yet to take a period of time.

During the War of Liberation China solved the tasks of the democratic revolution. The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 marked the basic conclusion of the democratic revolution and the beginning of the transition to socialism. It took another three years to conclude the land reform, but at the time the Republic was founded we immediately expropriated the bureaucratic capitalist enterprises — 80 percent of the fixed assets of our industry and transport — and converted them to ownership by the whole people.

During the War of Liberation we raised antibureaucratic capitalist slogans as well as anti-imperialist and antifeudal ones. The struggle against bureaucratic capitalism had a two sided character: it had a democratic revolutionary character insofar as it amounted to opposition to comprador capitalism,[4] but it had a socialist character insofar as it amounted to opposition to the big bourgeoisie.

After the war of resistance was won, the Nationalist Party [KMT] took over a very large portion of bureaucratic capital from Japan and Germany and Italy. The ratio of bureaucratic to national [i.e., Chinese] capital was 8 to 2. After liberation we expropriated all bureaucratic capital, thus eliminating the major components of Chinese capitalism.[5]

But it would be wrong to think that after the liberation of the whole country “the revolution in its earliest stages had only in the main the character of a bourgeois democratic revolution and not until later would it gradually develop into a socialist revolution.” [No page reference]

6. Violence and the Proletarian Dictatorship

On page 333 the text could be more precise in its use of the concept of violence. Marx and Engels always said that “the state is by definition an instrument of violence employed to suppress the opposing class.” And so it can never be said that “the proletarian dictatorship does not use violence purely and simply in dealing with the exploiter and may even not use it primarily.”

When its life is at stake the exploiting class always resorts to force. Indeed, no sooner do they see the revolution start up than they suppress it with force. The text says, “Historical experience proves that the exploiting class is utterly unwilling to cede political power to the people and uses armed force to oppose the people’s political power.” This is not a complete way of stating the matter. It is not only after the people have organized revolutionary political power that the exploiting class will oppose it with force, but even at the very moment when the people rise up to seize political power, the exploiters promptly use violence to suppress the revolutionary people.

The purpose of our revolution is to develop the society’s forces of production. Toward this end we must first overthrow the enemy. Second we must suppress its resistance. How could we do this without the revolutionary violence of the people?

Here the book turns to the “substance” of the proletarian dictatorship and the primary responsibilities of the working class and laboring people in general in the socialist revolution. But the discussion is incomplete as it leaves out the suppression of the enemy as well as the remoulding of classes. Landlords, bureaucrats, counter-revolutionaries, and undesirable elements have to be remoulded; the same holds true for the capitalist class, the upper stratum of the petit bourgeoisie, and the middle [Only in the 1969 text. Note by translator.] peasants. Our experience shows that remoulding is difficult. Those who do not undergo persistent repeated struggle can not be properly remoulded. To eliminate thoroughly any remaining strength of the bourgeoisie and any influence they may have will take one or two decades at the least and may even require half a century. In the rural areas, where basic commune ownership has been put into effect, private ownership has been transformed into state ownership. The entire country abounds with new cities and new major industry. Transportation and communications for the entire country have been modernized. Truly, the economic situation has been completely changed, and for the first time the peasants’ worldview is bound to be turned around completely step by step. (Here in speaking of “primary responsibilities” the book uses Lenin’s words differently from his original intention.)

To write or speak in an effort to suit the tastes of the enemy, the imperialists, is to defraud the masses and as a result to comfort the enemy while keeping one’s own class in ignorance.

7. The Form of the Proletarian State

On page 334 the book says, “the proletarian state can take various forms.” True enough, but there is not much difference essentially between the proletarian dictatorship in the people’s democracies and the one established in Russia after the October Revolution. Also, the soviets of the Soviet Union and our own people’s congresses were both representative assemblies, different in name only. In China the people’s congresses included those participating as representatives of the bourgeoisie, representatives who had split off from the Nationalist Party, and representatives who were prominent democratic figures. All of them accepted the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. One group among these tried to stir up trouble, but failed.[6] Such an inclusive form may appear different from the soviet, but it should be remembered that after the October Revolution the soviets included representatives of the Menshevik rightist Social Revolutionary Party, a Trotskyite faction, a Bukharin faction, a Zinoviev faction, and so forth. Nominally representatives of the workers and peasants, they were virtual representatives of the bourgeoisie. The period after the October Revolution was a time when the proletariat accepted a large number of personnel from the Kerensky government — all of whom were bourgeois elements. Our own central people’s government was set up on the foundation of the North China People’s Government. All members of the various departments were from the base areas, and the majority of the mainstay cadres were Communist Party members.

8. Transforming Capitalist Industry and Commerce

On page 335 there is an incorrect explanation of the process by which capitalist ownership changed into state ownership in China. The book only explains our policy toward national capital but not our policy toward bureaucratic capital (expropriation). In order to convert the property of the bureaucratic capitalist to public ownership we chose the method of expropriation.

In paragraph 2 of page 335 the experience of passing through the state capitalist form in order to transform capitalism is treated as a singular and special experience; its universal significance is denied. The countries of Western Europe and the United States have a very high level of capitalist development, and the controlling positions are held by a minority of monopoly capitalists. But there are a great number of small and middle capitalists as well. Thus it is said that American capital is concentrated but also widely distributed. After a successful revolution in these countries monopoly capital will undoubtedly have to be expropriated, but will the small and middle capitalists likewise be uniformly expropriated? It may well be the case that some form of state capitalism will have to be adopted to transform them.

Our northeast provinces may be thought of as a region with a high level of capitalist development. The same is true for Kiangsu (with centers in Shanghai and the southern part of the province). If state capitalism could work in these areas, tell me why the same policy could not work in other countries which resemble these provincial sectors?

The method the Japanese used when they held our northeast provinces was to eliminate the major local capitalists and turn their enterprises into Japanese state-managed, or in some cases monopoly capitalist enterprises. For the small and middle capitalists they established subsidiary companies as a means of imposing control.

Our transformation of national capital passed through three stages: private manufacture on state order, unified government purchase and sale of private output, joint state private operation (of individual units and of whole complexes). Each phase was carried out in a methodical way. This prevented any damage to production, which actually developed as the transformation progressed. We have gained much new experience with state capitalism; for one example, the providing of capitalists with fixed interest after the joint state-private operation phase.[7]

9. Middle Peasants

After land reform, land was not worth money and the peasants were afraid to “show themselves.” There were comrades who at one time considered this situation unsatisfactory, but what happened was that in the course of class struggles which disgraced landlords and rich peasants, the peasantry came to view poverty as dignified and wealth as shameful. This was a welcome sign, one which showed that the poor peasants had politically overturned the rich peasants and established their dominance in the villages.

On page 339 it says that the land taken from the rich peasants and given to the poor and middle peasants was land the government had expropriated and then parcelled out. This looks at the matter as a grant by royal favour, forgetting that class struggles and mass mobilizations had been set in motion, a right deviationist point of view. Our approach was to rely on the poor peasants, to unite with the majority of middle peasants (lower middle peasants) and seize the land from the landlord class. While the party did play a leading role, it was against doing everything itself and thus substituting for the masses. Indeed, its concrete practice was to “pay call on the poor to learn of their grievances,” to identify activist elements, to strike roots and pull things together, to consolidate nuclei, to promote the voicing of grievances, and to organize the class ranks — all for the purpose of unfolding the class struggle.

The text says “the middle peasants became the principal figures in the villages.” This is an unsatisfactory assertion. To proclaim the middle peasants as the principals, commending them to the gods, never daring to offend them, is bound to make former poor peasants feel as if they had been put in the shade. Inevitably this opens the way for middle peasants of means to assume rural leadership.

The book makes no analysis of the middle peasant. We distinguish between upper and lower middle peasants and further between old and new within those categories, regarding the new as slightly preferable. Experience in campaign after campaign has shown that the poor peasant, the new lower middle peasant, and the old lower middle peasant have a comparatively good political attitude. They are the ones who embrace the people’s communes. Among the upper middle peasants and the prosperous middle peasants there is a group that supports the communes as well as one that opposes them. According to materials from Hopei province the total number of production teams there comes to more than forty thousand, 50 percent of which embrace the communes without reservation, 35 percent of which basically accept them but with objections or doubts on particular questions, 15 percent of which oppose or have serious reservations about the communes. The opposition of this last group is due to the fact that the leadership of the teams fell to prosperous middle peasants or even undesirable elements. During this process of education in the struggle between the two roads, if the debate is to develop among these teams, their leadership will have to change. Clearly, then, the analysis of the middle peasant must be pursued. For the matter of whose hands hold rural leadership has tremendous bearing on the direction of developments there.

On page 340 the book says, “Essentially the middle peasant has a twofold character.” This question also requires concrete analysis. The poor, lower middle, upper middle, and prosperous middle peasants in one sense are all workers, but in another they are private owners. As private owners their points of view are respectively dissimilar. Poor and lower middle peasants may be described as semiprivate owners whose point of view is comparatively easily altered. By contrast, the private owner’s point of view held by the upper middle and the prosperous peasants has greater substance, and they have consistently resisted cooperativization.

10. The Worker-Peasant Alliance

The third and fourth paragraphs on page 340 are concerned with the importance of the worker-peasant alliance but fail to go into what must be done before the alliance can be developed and consolidated. The text, again, deals with the need of the peasants to press forward with the transformation of the small producers but fails to consider how to advance the process, what kinds of contradictions may be found at each stage of the transformation, and how they may be resolved. And, the text does not discuss the measures and tactics for the entire process.

Our worker-peasant alliance has already passed through two stages. The first was based on the land revolution, the second on the cooperative movement. If cooperativization had not been set in motion the peasantry inevitably would have been polarized, and the worker-peasant alliance could not have been consolidated. In consequence, the policy of “unified government purchase and sale of private output”[8] could not have been persevered in. The reason is that that policy could be maintained and made to work thoroughly only on the basis of cooperativization. At the present time our worker-peasant alliance has to take the next step and establish itself on the basis of mechanization. For to have simply the cooperative and commune movements without mechanization would once again mean that the alliance could not be consolidated. We still have to develop the cooperatives into people’s communes. We still have to develop basic ownership by the commune team into basic ownership by the commune and that further into state ownership. When state ownership and mechanization are integrated we will be able to begin truly to consolidate the worker-peasant alliance, and the differences between workers and peasants will surely be eliminated step by step.

11. The Transformation of Intellectuals

Page 341 is devoted exclusively to the problem of fostering the development of intellectuals who are the workers’ and peasants’ own, as well as the problem of involving bourgeois intellectuals in socialist construction. However, the text fails to deal with the transformation of intellectuals. Not only the bourgeois intellectuals but even those of worker or peasant origin need to engage in transformation because they have come under the manifold influence of the bourgeoisie. Liu Shao-t’ang, of artistic and literary circles, who, after becoming an author, became a major opponent of socialism, exemplifies this. Intellectuals usually express their general outlook through their way of looking at knowledge. Is it privately owned or publicly owned? Some regard it as their own property, for sale when the price is right and not otherwise. Such are mere “experts” and not “reds”[9] who say the party is an “outsider” and “cannot lead the insiders.” Those involved in the cinema claim that the party cannot lead the cinema. Those involved in musicals or ballet claim that the party cannot offer leadership there. Those in atomic science say the same. In sum, what they are all saying is that the party cannot lead anywhere. Remoulding of the intellectuals is an extremely important question for the entire period of socialist revolution and construction. Of course it would be wrong to minimize this question or to adopt a concessive attitude toward things bourgeois.

Again on page 341 it says that the fundamental contradiction in the transition economy is the one between capitalism and socialism. Correct. But this passage speaks only of setting struggles in motion to see who will emerge the victor in all realms of economic life. None of this is complete. We would put it as follows: a thoroughgoing socialist revolution must advance along the three fronts of politics, economics, and ideology.

The text says that we absorb bourgeois elements so that they may participate in the management of enterprises and the state. This is repeated on page 357. [Page 341, according to the 1967 text.: Note by translator.] But we insist on the responsibility for remoulding the bourgeois elements. We help them change their lifestyle, their general outlook, and also their viewpoint on particular issues. The text, however, makes no mention of remoulding.

12. The Relationship Between Industrialization and

Agricultural Collectivization

The book sees socialist industrialization as the precondition for agricultural collectivization. This view in no way corresponds to the situation in the Soviet Union itself, where collectivization was basically realized between 1930 and 1932. Though they had then more tractors than we do now, still and all the amount of arable land under mechanized cultivation was under 20.3 percent. Collectivization is not altogether determined by mechanization, and so industrialization is not the precondition for it.

Agricultural collectivization in the socialist countries of Eastern Europe was completed very slowly, mainly because after land reform, they did not strike while the iron was hot but delayed for a time. In some of our own old base areas too, a section of the peasantry was satisfied with the reform and unwilling to proceed further. This situation did not depend at all on whether or not there was industrialization.

13. War and Revolution

On pages 352-54 it is argued that the various people’s democracies of Eastern Europe “were able to build socialism even though there was neither civil war nor armed intervention from abroad.” It is also argued that “socialist transformation in these countries was realized without the ordeal of civil war.” It would have been better to say that what happened in these countries is that a civil war was waged in the form of international war, that civil and international war were waged together. The reactionaries of these countries were ploughed under by the Soviet Red Army. To say that there was no civil war in these countries would be mere formalism that disregards substance.

The text says that in the countries of Eastern Europe after the revolution “parliaments became the organs for broadly representing the people’s interests.” In fact, these parliaments were completely different from the bourgeois parliaments of old, bearing resemblance in name only. The Political Consultative Conference we had during the early phase of Liberation was no different in name from the Political Consultative Conference of the Nationalist period. During our negotiations with the Nationalists we were indifferent to the conference but Chiang Kai-shek was very interested in it. After Liberation we took over their signboard and called into session a nationwide Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, which served as a provisional people’s congress.[10]

The text says that China “in the process of revolutionary struggle organized a people’s democratic united front.” (p. 357) Why only “revolutionary struggle” and not “revolutionary war?” From 1927 down to the nationwide victory we waged twenty-two years of long-term uninterrupted war. And even before that, starting with the bourgeois revolution of 1911, there was another fifteen years’ warfare. The chaotic wars of the warlords under the direction of imperialists should also be counted. Thus, from 1911 down to the War to Resist America and Aid Korea, it may be said that continual wars were waged in China for forty years — revolutionary warfare and counter-revolutionary warfare. And, since its founding, our party has joined or led wars for thirty years.

A great revolution must go through a civil war. This is a rule. And to see the ills of war but not its benefits is a onesided view. It is of no use to the people’s revolution to speak onesidedly of the destructiveness of war.

14. Is Revolution Harder in Backward Countries?

In the various nations of the West there is a great obstacle to carrying through any revolution and construction movement i.e., the poisons of the bourgeoisie are so powerful that they have penetrated each and every corner. While our bourgeoisie has had, after all, only three generations, those of England and France have had a 250-300 year history of development and their ideology and modus operandi have influenced all aspects and strata of their societies. Thus the English working class follows the Labour Party, not the Communist Party.

Lenin says, “The transition from capitalism to socialism will be more difficult for a country the more backward it is.” This would seem incorrect today. Actually, the transition is less difficult the more backward an economy is, for the poorer they are the more the people want revolution. In the capitalist countries of the West the number of people employed is comparatively high, and so is the wage level. Workers there have been deeply influenced by the bourgeoisie, and it would not appear to be all that easy to carry through a socialist transformation. And since the degree of mechanization is high, the major problem after a successful revolution would not be advancing mechanization but transforming the people. Countries of the East, such as China and Russia, had been backward and poor, but now not only have their social systems moved well ahead of those of the West, but even the rate of development of their productive forces far outstrips that of the West. Again, as in the history of the development of the capitalist countries, the backward overtake the advanced as America overtook England, and as Germany later overtook England early in the twentieth century.

15. Is Large-Scale Industry the Foundation of Socialist Transformation?

On page 364 [Page 349, according to the 1967 text.: Note by translator.] the text says, “Countries that have taken the road of socialist construction face the task of eliminating as quickly as possible the after-effects of capitalist rule in order to accelerate the development of large industry (the basis for the socialist transformation of the economy).” It is not enough to assert that the development of large industry is the foundation for the socialist transformation of the economy. All revolutionary history shows that the full development of new productive forces is not the prerequisite for the transformation of backward production relations. Our revolution began with Marxist-Leninist propaganda, which served to create new public opinion in favor of the revolution. Moreover, it was possible to destroy the old production relations only after we had overthrown a backward superstructure in the course of revolution. After the old production relations had been destroyed new ones were created, and these cleared the way for the development of new social productive forces. With that behind us we were able to set in motion the technological revolution to develop social productive forces on a large scale. At the same time, we still had to continue transforming the production relations and ideology.

This textbook addresses itself only to material preconditions and seldom engages the question of the superstructure, i.e., the class nature of the state, philosophy, and science. In economics the main object of study is the production relations. All the same, political economy and the materialist historical outlook are close cousins. It is difficult to deal clearly with problems of the economic base and the production relations if the question of the superstructure is neglected.

16. Lenin’s Discussion of the Unique

Features of Taking the Socialist Road

On page 375 a passage from Lenin is cited. It is well expressed and quite helpful for defending our work methods. “The level of consciousness of the residents, together with the efforts they have made to realize this or that plan, are bound to be reflected in the unique features of the road they take toward socialism.” Our own “politics in command” is precisely for raising the consciousness in our neighbourhoods. Our own Great Leap Forward is precisely an “effort to realize this or that plan.”

17. The Rate of Industrialization Is a Critical Problem

The text says, “As far as the Soviet Union is concerned, the rate of industrialization is a critical problem.” At present this is a critical problem for China, too. As a matter of fact, the problem becomes more acute the more backward industry is. This is true not only from country to country but also from one area to another in the same country. For example, our northeastern provinces and Shanghai have a comparatively strong base, and so state investment increased somewhat less rapidly there. In other areas, where the original industrial base was slight, and development was urgently needed, state investment increased quite rapidly. In the ten years that Shanghai has been liberated 2.2 billion Chinese dollars[11] have been invested, over 500 million by capitalists. Shanghai used to have over half a million workers, now the city has over 1 million, if we do not count the hundreds of thousands transferred out. This is only double the earlier worker population. When we compare this with certain new cities where the work force has increased enormously we can see plainly that in areas with a deficient industrial base the problem of rate is all the more critical. Here the text only says that political circumstances demand the high rate and does not explain whether or not the socialist system itself can attain the high rate. This is onesided. If there is only the need and not the capability, tell me, how is the high rate to be achieved?[12]

18. Achieve a High Rate of Industrialization by Concurrent Promotion of Small, Medium, and Large Enterprise

On page 381 the text touches on our broad development of small- and medium-scale enterprise but fails to reflect accurately our philosophy of concurrent promotion of native and foreign, small, medium, and large enterprise. The text says we “determined upon extensive development of small and medium-scale enterprises because of the utter backwardness of our technological economy, the size of our populations and very serious employment problems.” But the problem by no means lies in technological age, population size, or the need to increase employment. Under the guidance of the larger enterprises we are developing the small and the medium; under the guidance of the foreign we are adopting native methods wherever we can — mainly for the sake of achieving the high rate of industrialization.

19. Is Long-Term Coexistence Between Two Types of Socialist Ownership Possible?

On page 386 it says, “A socialist state and socialist construction can not be established on two different bases for any length of time. That is to say, they can not be established on the base of socialist industry, the largest and most unified base, and on the base of the peasant petty commodity economy, which is scattered and backward.” This point is well taken, of course, and we therefore extend the logic to reach the following conclusion: The socialist state and socialist construction cannot be established for any great length of time on the basis of ownership by the whole people and ownership by the collective as two different bases of ownership.

In the Soviet Union the period of coexistence between the two types of ownership has lasted too long. The contradictions between ownership of the whole people and collective ownership are in reality contradictions between workers and peasants. The text fails to recognize such contradictions.

In the same way prolonged coexistence of ownership by the whole people with ownership by the collectives is bound to become less and less adaptable to the development of the productive forces and will fail to satisfy the ever increasing needs of peasant consumption and agricultural production or of industry for raw materials. To satisfy such needs we must resolve the contradiction between these two forms of ownership, transform ownership by the collectives into ownership by the whole people, and make a unified plan for production and distribution in industry and agriculture on the basis of ownership by the whole people for an indivisible nation.

The contradictions between the productive forces and the production relations unfold without interruption. Relations that once were adapted to the productive forces will no longer be so after a period of time. In China, after we finished organizing the advanced cooperatives, the question of having both large and small units came up in every special district and in every county.

In socialist society the formal categories of distribution according to labor, commodity production, the law of value, and so forth are presently adapted to the demands of the productive forces. But as this development proceeds, the day is sure to come when these formal categories will no longer be adapted. At that time these categories will be destroyed by the development of the productive forces; their life will be over. Are we to believe that in a socialist society there are economic categories that are eternal and unchanging? Are we to believe that such categories as distribution according to labor and collective ownership are eternal — unlike all other categories, which are historical [hence relative]?

20. The Socialist Transformation of Agriculture Cannot Depend Only on Mechanization

Page 392 states, “The machine and tractor stations are important tools for carrying through the socialist transformation in agriculture.” Again and again the text emphasizes how important machinery is for the transformation. But if the consciousness of the peasantry is not raised, if ideology is not transformed, and you are depending on nothing but machinery — what good will it be? The question of the struggle between the two roads, socialism and capitalism, the transformation and re-education of people — these are the major questions for China.

The text on page 395 says that in carrying through the tasks of the early stages of general collectivization the question of the struggle against hostile rich peasants comes up. This of course is correct. But in the account the text gives of rural conditions after the formation of cooperatives the question of a prosperous stratum is dropped, nor is there any mention of such contradictions as those between the state, the collectives, and individuals, between accumulation and consumption[13] and so forth.

Page 402 says, “Under conditions of high tide in the agricultural cooperative movement the broad masses of the middle peasantry will not waver again.” This is too general. There is a section of rich middle peasants that is now wavering and will do so in the future.

21. So-Called Full Consolidation

“. . . fully consolidated the collective farm system,” it says on page 407. “Full consolidation” — a phrase to make one uneasy. The consolidation of anything is relative. How can it be “full”? What if no one died since the beginning of mankind, and everyone got “fully consolidated”? What kind of a world would that be! In the universe, on our globe, all things come into being, develop, and pass away ceaselessly. None of them is ever “fully consolidated.” Take the life of a silkworm. Not only must it pass away in the end, it must pass through four stages of development during its lifetime: egg, silkworm, pupa, moth. It must move on from one stage to the next and can never fully consolidate itself in any one stage. In the end, the moth dies, and its old essence becomes a new essence (as it leaves behind many eggs). This is a qualitative leap. Of course, from egg to worm, from worm to pupa, from pupa to moth clearly are more than quantitative changes. There is qualitative transformation too, but it is partial qualitative transformation. A person, too, in the process of moving through life toward death, experiences different stages: childhood, adolescence, youth, adulthood and old age. From life to death is a quantitative process for people, but at the same time they are pushing forward the process of partial qualitative change. It would be absurd to think that from youth to old age is but a quantitative increase without qualitative change. Inside the human organism cells are ceaselessly dividing, old ones dying and vanishing, new ones emerging and growing. At death there is a complete qualitative change, one that has come about through the preceding quantitative changes as well as the partial qualitative changes that occur during the quantitative changes. Quantitative change and qualitative change are a unity of opposites. Within the quantitative changes there are partial qualitative changes. One cannot say that there are no qualitative changes within quantitative changes. And within qualitative changes there are quantitative changes. One cannot say that there are no quantitative changes within qualitative changes.

In any lengthy process of change, before entering the final qualitative change, the subject must pass through uninterrupted quantitative changes and a good many partial qualitative changes. But the final qualitative change cannot come about unless there are partial qualitative changes and considerable quantitative change. For example, a factory of a given plant and size changes qualitatively as the machinery and other installations are renovated a section at a time. The interior changes even though the exterior and the size do not. A company of soldiers is no different. After it has fought a battle and lost dozens of men, a hundred-soldier company will have to replace its casualties. Fighting and replenishing continuously — this is how the company goes through uninterrupted partial qualitative change. As a result the company continues to develop and harden itself.

The crushing of Chiang Kai-shek was a qualitative change which came about through quantitative change. For example, there had to be a three-and-a-half-year period during which his army and political power were destroyed a section at a time. And, within this quantitative change qualitative change is to be found. The War of Liberation went through several different stages, and each new stage differed qualitatively from the preceding stages. The transformation from individual to collective economy was a process of qualitative transformation. In our country this process consisted of mutual aid teams, early-stage cooperatives, advanced cooperatives, and people’s communes.[14] Such different stages of partial qualitative change brought a collective economy out of an individual economy.

The present socialist economy in our country is organized through two different forms of public ownership, ownership by the whole people and collective ownership. This socialist economy has had its own birth and development. Who would believe that this process of change has come to an end, and that we will say, “These two forms of ownership will continue to be fully consolidated for all time?” Who would believe that such formulas of a socialist society as “distribution according to labor,” “commodity production,” and “the law of value” are going to live forever? Who would believe that there is only birth and development but no dying away and transformation and that these formulas unlike all others are ahistorical?

Socialism must make the transition to communism. At that time there will be things of the socialist stage that will have to die out. And, too, in the period of communism there will still be uninterrupted development. It is quite possible that communism will have to pass through a number of different stages. How can we say that once communism has been reached nothing will change, that everything will continue “fully consolidated,” that there will be quantitative change only, and no partial qualitative change going on all the time.

The way things develop, one stage leads on to another, advancing without interruption. But each and every stage has a “boundary.” Every day we read from, say, four o’clock and end at seven or eight. That is the boundary. As far as socialist ideological remoulding goes, it is a long-term task. But each ideological campaign reaches its conclusion, that is to say has a boundary. On the ideological front, when we will have come through uninterrupted quantitative changes and partial qualitative changes, the day will arrive when we will be completely free of the influence of capitalist ideology. At that time the qualitative changes of ideological remoulding will have ended, but only to be followed by the quantitative changes of a new quality.

The construction of socialism also has its boundary. We have to keep tabs: for example, what is to be the ratio of industrial goods to total production, how much steel is to be produced, how high can the people’s living standard be raised, etc.? But to say that socialist construction has a boundary hardly means that we do not want to take the next step, to make the transition to communism. It is possible to divide the transition from capitalism to communism into two stages: one from capitalism to socialism, which could be called underdeveloped socialism; and one from socialism to communism, that is, from comparatively underdeveloped socialism to comparatively developed socialism, namely, communism. This latter stage may take even longer than the first. But once it has been passed through, material production and spiritual prosperity will be most ample. People’s communist consciousness will be greatly raised, and they will be ready to enter the highest stage of communism.

On page 409 it says that after the forms of socialist production have been firmly established, production will steadily and rapidly expand. The rate of productivity will climb steadily. The text uses the term steadily or without interruption a good many times, but only to speak of quantitative transformation. There is little mention of partial qualitative change.

22. War and Peace

On page 408 it says that in capitalist societies “a crisis of surplus production will inevitably be created, causing unemployment to increase.” This is the gestation of war. It is difficult to believe that the basic principles of Marxist economics are suddenly without effect, that in a world where capitalist institutions still exist war can be fully eliminated.

Can it be said that the possibility of eliminating war for good has now arisen? Can it be said that the possibility of plying all the world’s wealth and resources to the service of mankind has arisen? This view is not Marxism, it has no class analysis, and it has not distinguished clearly between conditions under bourgeois and proletarian rule. If you do not eliminate classes, how can you eliminate war?

We will not be the ones to determine whether a world war will be waged or not. Even if a non-belligerency agreement is signed, the possibility of war will still exist. When imperialism wants to fight no agreement is going to be taken into account. And, if it comes, whether atomic or hydrogen weapons will be used is yet another question. Even though chemical weapons exist, they have not been used in time of war; conventional weapons were used after all. Even if there is no war between the two camps, there is no guarantee war will not be waged within the capitalist world. Imperialism may make war on imperialism. The bourgeoisie of one imperialist country may make war on its proletariat. Imperialism is even now waging war against colony and semicolony. War is one form of class conflict. But classes will not be eliminated except through war. And war cannot be eliminated for good except through the elimination of classes. If revolutionary war is not carried on, classes cannot be eliminated. We do not believe that the weapons of war can be eliminated without destroying classes. It is not possible. In the history of class societies any class or state is concerned with its “position of strength.” Gaining such positions has been history’s inevitable tendency. Armed force is the concrete manifestation of the real strength of a class. And as long as there is class antagonism there will be armed forces. Naturally, we are not wishing for war. We wish for peace. We favor making the utmost effort to stop nuclear war and to strive for a mutual nonaggression pact between the two camps. To strive to gain even ten or twenty years’ peace was what we advocated long ago. If we can realize this wish, it would be most beneficial for the entire socialist camp and for China’s socialist construction as well.

On page 409 it says that at this time the Soviet Union is no longer encircled by capitalism. This manner of speaking runs the risk of lulling people to sleep. Of course the present situation has changed greatly from when there was only one socialist country. West of the Soviet Union there are now the various socialist countries of Eastern Europe. East of the Soviet Union are the socialist countries of China, Korea, Mongolia, and Vietnam. But the guided missiles have no eyes and can strike targets thousands or tens of thousands of kilometers away. All around the socialist camp American military bases are deployed, pointed toward the Soviet Union and the other socialist countries. Can it be said that the Soviet Union is no longer inside the ring of missiles?

23. Is Unanimity the Motive Force of Social Development?

On page 413 and 417 it says that socialism makes for the “solidarity of unanimity” and is “hard as a rock.” It says that unanimity is the “motive force of social development.”

This recognizes only the unanimity of solidarity but not the contradictions within a socialist society, nor that contradiction is the motive force of social development. Once it is put this way, the law of the universality of contradiction is denied, the laws of dialectics are suspended. Without contradictions there is no movement, and society always develops through movement. In the era of socialism, contradictions remain the motive force of social development. Precisely because there is no unanimity there is the responsibility for unity, the necessity to fight for it. If there were 100 percent unanimity always, then what explains the necessity for persevering in working for unity?

24. Rights of Labor Under Socialism

On page 414 we find a discussion of the rights labor enjoys but no discussion of labor’s right to run the state, the various enterprises, education, and culture. Actually, this is labor’s greatest right under socialism, the most fundamental right, without which there is no right to work, to an education, to vacation, etc.

The paramount issue for socialist democracy is: Does labor have the right to subdue the various antagonistic forces and their influences? For example, who controls things like the newspapers, journals, broadcast stations, the cinema? Who criticizes? These are a part of the question of rights. If these things are in the hands of right opportunists (who are a minority) then the vast nationwide majority that urgently needs a great leap forward will find itself deprived of these rights. If the cinema is in the hands of people like Chung Tien-p’ei,[15] how are the people supposed to realize their own rights in that sector? There is a variety of factions among the people. Who is in control of the organs and enterprises bears tremendously on the issue of guaranteeing the people’s rights. If Marxist-Leninists are in control, the rights of the vast majority will be guaranteed. If rightists or right opportunists are in control, these organs and enterprises may change qualitatively, and the people’s rights with respect to them cannot be guaranteed. In sum, the people must have the right to manage the superstructure. We must not take the rights of the people to mean that the state is to be managed by only a section of the people, that the people can enjoy labor rights, education rights, social insurance, etc., only under the management of certain people.

25. Is the Transition to Communism a Revolution?

On page 417 it says, “Under socialism there will be no class or social group whose interests conflict with communism and therefore the transition to communism will come about without social revolution.”

The transition to communism certainly is not a matter of one class overthrowing another. But that does not mean there will be no social revolution, because the superseding of one kind of production relations by another is a qualitative leap, i.e., a revolution. The two transformations — of individual economy to collective, and collective economy to public — in China are both revolutions in the production relations. So to go from socialism’s “distribution according to labor” to communism’s “distribution according to need” has to be called a revolution in the production relations. Of course, “distribution according to need” has to be brought about gradually. Perhaps when the principal material goods can be adequately supplied we can begin to carry out such distribution with those goods, extending the practice to other goods on the basis of further development of the productive forces.

Consider the development of our people’s communes. When we changed from basic ownership by the team to basic ownership by the commune, was a section of the people likely to raise objections or not? This is a question well worth our study. A determinative condition for realizing this changeover was that the commune-owned economy’s income was more than half of the whole commune’s total income. To realize the basic commune-ownership system is generally of benefit to the members of the commune. Thus we estimate that there should be no objection on the part of the vast majority. But at the time of changeover the original team cadres could no longer be relatively reduced under the circumstances. Would they object to the changeover?

Although classes may be eliminated in a socialist society, in the course of its development there are bound to be certain problems with “vested interest groups” which have grown content with existing institutions and unwilling to change them. For example, if the rule of distribution according to labor is in effect they benefit from higher pay for more work, and when it came time to change over to “distribution according to need” they could very well be uncomfortable with the new situation. Building any new system always necessitates some destruction of old ones. Creation never comes without destruction. If destruction is necessary it is bound to arouse some opposition. The human animal is queer indeed. No sooner do people gain some superiority than they assume airs . . . it would be dangerous to ignore this.

26. The Claim That “for China There Is No Necessity to Adopt Acute Forms of Class Struggle”

There is an error on page 419. After the October Revolution Russia’s bourgeoisie saw that the country’s economy had suffered severe damage, and so they decided that the proletariat could not change the situation and lacked the strength to maintain its political power. They judged that they only had to make the move and proletarian political power could be overthrown. At this point they carried out armed resistance, thus compelling the Russian proletariat to take drastic steps to expropriate their property. At that time neither class had much experience.

To say that China’s class struggle is not acute is unrealistic. It was fierce enough! We fought for twenty-two years straight. By waging war we overthrew the rule of the bourgeoisie’s Nationalist Party, and expropriated bureaucratic capital, which amounted to 80 percent of our entire capitalist economy. Only thus was it possible for us to use peaceful methods to remold the remaining 20 percent of national capital. In the remoulding process we still had to go through such fierce struggles as the “three-antis” and the “five-antis” campaigns.[16]

Page 420 incorrectly describes the remoulding of bourgeois industrial and commercial enterprises. After Liberation the national bourgeoisie was forced to take the road of socialist remoulding. We brought down Chiang Kai-shek, expropriated bureaucratic capital, concluded the land reform, carried out the “three-antis” and “five-antis” campaigns, and made the cooperatives a working reality. We controlled the markets from the beginning. This series of transformations forced the national bourgeoisie to accept remoulding step by step. From yet another point of view, the Common Program stipulated that various kinds of economic interests were to be given scope. This enabled the capitalists to try for what profits they could. In addition, the constitution gave them the right to a ballot and a living. These things helped the bourgeoisie to realize that by accepting remoulding they could hold onto a social position and also play a certain role in the culture and in the economy.

In joint state-private enterprises the capitalists have no real managerial rights over the enterprise. Production is certainly not jointly managed by the capitalists and representatives of the public. Nor can it be said that “Capital’s exploitation of labor has been limited.” It has been virtually curtailed. The text seems to have missed the idea that the jointly operated enterprises we are speaking of were 75 per cent socialist. Of course at present they are 90 percent socialist or more.

The remoulding of capitalist industry and commerce has been basically concluded. But if the capitalists had the chance they would attack us without restraint. In 1957 we pushed back the onslaught of the right.[17] In 1959, through their representatives in the party, they again set in motion an attack against us.[18] Our policy toward the national capitalists is to take them along with us and then to encompass them.

The text uses Lenin’s statement that state capitalism “continues the class struggle in another form.” This is correct. (p. 421)

27. The Time Period for Building Socialism

On page 423 it says that we “concluded” the socialist revolution on the political and ideological fronts in 1957.[19] We would rather say that we won a decisive victory.

On the same page it says that we want to turn China into a strong socialist country within ten to fifteen years. Now this is something we agree on! This means that after the second five-year plan we will have to go through another two five-year plans until 1972 (or 1969 if we strive to beat the schedule by two or three years). In addition to modernizing industry and agriculture, science and culture, we have to modernize national defence. In a country such as ours bringing the building of socialism to its conclusion is a tremendously difficult task. In socialist construction we must not speak of “early.”

28. Further Discussion of the Relationship Between Industrialization and Socialist Transformation

On page 423 it says that reform of the system of ownership long before the realization of industrialization was a circumstance created by special conditions in China This is an error. Eastern Europe, like China, “benefited from the existence of the mighty socialist camp and the help of an industrialized country as developed as the Soviet Union.” The question is, what was the reason Eastern European countries could not complete the socialist transformation in the ownership system (including agriculture) before industrialization became a reality? [Cf. Chapter 28, paragraph 1, of the 1967 edition: Page 423 says, “Given the special conditions in China, before socialist industrialization became a reality, it was thanks to the existence of the mighty socialist camp and the help of a powerful, highly developed industrial nation like the Soviet Union that the reform of the ownership system (including agriculture) achieved victory.” This is an error. The countries of Eastern Europe no less than China “had the existence of the powerful socialist camp and the help of as highly developed an industrial nation as the Soviet Union.” Why could they not complete socialist transformation in the ownership system (including agriculture) before industrialization became a reality? Note by translator.] Turning to the relationship between industrialization and socialist transformation, the truth is that in the Soviet Union itself the problem of ownership was settled before industrialization became a reality.

Similarly, from the standpoint of world history, the bourgeois revolutions and the establishment of the bourgeois nations came before, not after, the Industrial Revolution. The bourgeoisie first changed the superstructure and took possession of the machinery of state before carrying on propaganda to gather real strength. Only then did they push forward great changes in the production relations. When the production relations had been taken care of and they were on the right track they then opened the way for the development of the productive forces. To be sure, the revolution in the production relations is brought on by a certain degree of development of the productive forces, but the major development of the productive forces always comes after changes in the production relations. Consider the history of the development of capitalism. First came simple coordination, which subsequently developed into workshop handicrafts. At this time capitalist production relations were already taking shape, but the workshops produced without machines. This type of capitalist production relations gave rise to the need for technological advance, creating the conditions for the use of machinery. In England the Industrial Revolution (late eighteenth-early nineteenth centuries) was carried through only after the bourgeois revolution, that is, after the seventeenth century. All in their respective ways, Germany, France, America, and Japan underwent change in superstructure and production relations before the vast development of capitalist industry.

It is a general rule that you cannot solve the problem of ownership and go on to expand development of the productive forces until you have first prepared public opinion for the seizure of political power. Although between the bourgeois revolution and the proletarian revolution there are certain differences (before the proletarian revolution socialist production relations did not exist, while capitalist production relations were already beginning to grow in feudal society), basically they are alike.

Part II.

Chapters 24-29

29. Contradictions Between Socialist Production Relations and Productive Forces

Page 433 discusses only the “mutual function” of the production relations and the productive forces under socialism but not the contradictions between them. The production relations include ownership of the means of production, the relations among people in the course of production, and the distribution system. The revolution in the system of ownership is the base, so to speak. For example, after the entire national economy has become indivisibly owned by the whole people through the transition from collective to people’s ownership, although people’s ownership will certainly be in effect for a relatively long time, for all enterprises so owned important problems will remain. Should a central-local division of authority be in effect? Which enterprises should be managed by whom? In 1958 in some basic construction units a system of fixed responsibility for capital investment was put into effect. The result was a tremendous release of enthusiasm in these units. When the center cannot depend on its own initiative it must release the enthusiasm of the enterprise or the locality. If such enthusiasm is frustrated it hurts production.

We see then that contradictions to be resolved remain in the production relations under people’s ownership. As far as relations among people in the course of labor and the distribution relations go, it is all the more necessary to improve them unremittingly. For these areas it is rather difficult to say what the base is. Much remains to be written about human relations in the course of labor, e.g., concerning the leadership’s adopting egalitarian attitudes, the changing of certain regulations and established practices, “the two participations” [worker participation in management and management participation in productive labor], “the three combinations” [combining efforts of cadres, workers, and technicians], etc. Public ownership of primitive communes lasted a long time, but during that time people’s relations to each other underwent a good many changes, all the same, in the course of labor.

30. The Transition from Collective to People’s Ownership Is Inevitable

On page 435 the text says only that the existence of two forms of public ownership is objectively inevitable, but not that the transition from collective to people’s ownership is also objectively inevitable. This is an inescapable objective process, one presently in evidence in certain areas of our country. According to data from Cheng An county in Hopei province, communes growing industrial crops are thriving, accumulation levels have been raised to 45 percent,[20] and the peasants’ living standard is high. Should this situation continue to develop, if we do not let collective ownership become people’s ownership and resolve the contradiction, peasant living standards will surpass those of the workers to the detriment of both industrial and agricultural development.

On page 438 it says that “state-managed enterprises are not fundamentally different from cooperatives. . . . there exist two forms of public ownership. . . . sacred and inviolable.” There is no difference between collective and people’s ownership with reference to capitalism, but the difference becomes fundamental within the socialist economy. The text speaks of the two forms of ownership as “sacred and inviolable.” This is allowable when speaking of hostile forces, but when speaking of the process of development of public ownership it becomes wrong. Nothing can be regarded as unchanging. Ownership by the whole people itself also has a process of change.

After a good many years, after ownership by the people’s communes has changed into ownership by the whole people, the whole nation will become an indivisible system of ownership by the whole people. This will greatly spur the development of the productive forces. For a period of time this will remain a socialist system of ownership by the whole people, and only after another period will it be a communist system of ownership by the whole people. Thus, people’s ownership itself will have to progress from distribution according to labor to distribution according to need.

31. Individual Property

On page 439 it says, “Another part is consumer goods. . . . which make up the personal property of the workers.” This manner of expression tends to make people think that goods classified as “consumer” are to be distributed to the workers as their individual property. This is incorrect. One part of consumer goods is individual property, another is public property, e.g., cultural and educational facilities, hospitals, athletic facilities, parks, etc. Moreover, this part is increasing. Of course they are for each worker to enjoy, but they are not individual property.

On page 440 we find lumped together work income and savings, housing, household goods, goods for individual consumption, and other ordinary equipment. This is unsatisfactory because savings, housing, etc. are all derived from working people’s incomes.

In too many places this book speaks only of individual consumption and not of social consumption, such as public welfare, culture, health, etc. This is one-sided. Housing in our rural areas is far from what it should be. We must improve rural dwelling conditions in an orderly fashion. [Only in the 1969 text.: Note by translator.] Residential construction, particularly in cities, should in the main use collective social forces, not individual ones. If a socialist society does not undertake collective efforts what kind of socialism is there in the end? Some say that socialism is more concerned with material incentives than capitalism. Such talk is simply outrageous.

Here the text says that the wealth produced by collective farms includes individual property as well as subsidiary occupations. If we fail to propose transforming these subsidiary occupations into public ownership, the peasants will be peasants forever. A given social system must be consolidated in a given period of time. But consolidation must have a limit. If it goes on and on, the ideology reflecting the system is bound to become rigidified, causing the people to be unable to adjust their thinking to new developments.

On the same page there is mention of integrating individual and collective interests. It says, “Integration is realized by the following method: a member of society is compensated according to the quantity and quality of his labor so as to satisfy the principle of individual material interest.” Here, without discussion of the necessary reservations, the text places individual interest first. This is one-sided treatment of the principle of individual material interest.

According to page 441, “Public and individual interests are not at odds and can be gradually resolved.” This is spoken in vain and solves nothing. In a country like ours, if the contradictions among the people are not put to rights every few years, they will never get resolved.

32. Contradiction Is the Motive Force of Development in a Socialist Society

Page 443, paragraph 5, admits that in a socialist society contradictions between the productive forces and the production relations exist and speaks of overcoming such contradictions. But by no means does the text recognize that contradictions are the motive force.

The succeeding paragraph is acceptable; however, under socialism it is not only certain aspects of human relations and certain forms of leading the economy, but also problems of the ownership system itself (e.g., the two types of ownership) that may hinder the development of the productive forces.

Most dubious is the viewpoint in the next paragraph. It says, “The contradictions under socialism are not irreconcilable.” This does not agree with the laws of dialectics, which hold that all contradictions are irreconcilable. Where has there ever been a reconcilable contradiction? Some are antagonistic, some are non-antagonistic, but it must not be thought that there are irreconcilable and reconcilable contradictions.

Under socialism [The transcriber of the 1967 text comments that Comrade Mao may have meant “under communism”.] there may be no war but there is still struggle, struggle among sections of the people; there may be no revolution of one class overthrowing another, but there is still revolution. The transition from socialism to communism is revolutionary. The transition from one stage of communism to another is also. Then there is technological revolution and cultural revolution. Communism will surely have to pass through many stages and many revolutions.

Here the text speaks of relying on the “positive action” of the masses to overcome contradictions at the proper time. “Positive action” should include complicated struggles.

“Under socialism there is no class energetically plotting to preserve outmoded economic relations.” Correct, but in a socialist society there are still conservative strata and something like “vested interest groups.” There still remain differences between mental and manual labor, city and countryside, worker and peasant. Although these are not antagonistic contradictions they cannot be resolved without struggle.

The children of our cadres are a cause of discouragement. They lack experience of life and of society, yet their airs are considerable and they have a great sense of superiority. They have to be educated not to rely on their parents or martyrs of the past but entirely on themselves.