I had anticipated that my overseas itinerary would include a stopover in prison at some point, and in Paris that moment finally arrived.

I had anticipated that my overseas itinerary would include a stopover in prison at some point, and in Paris that moment finally arrived.

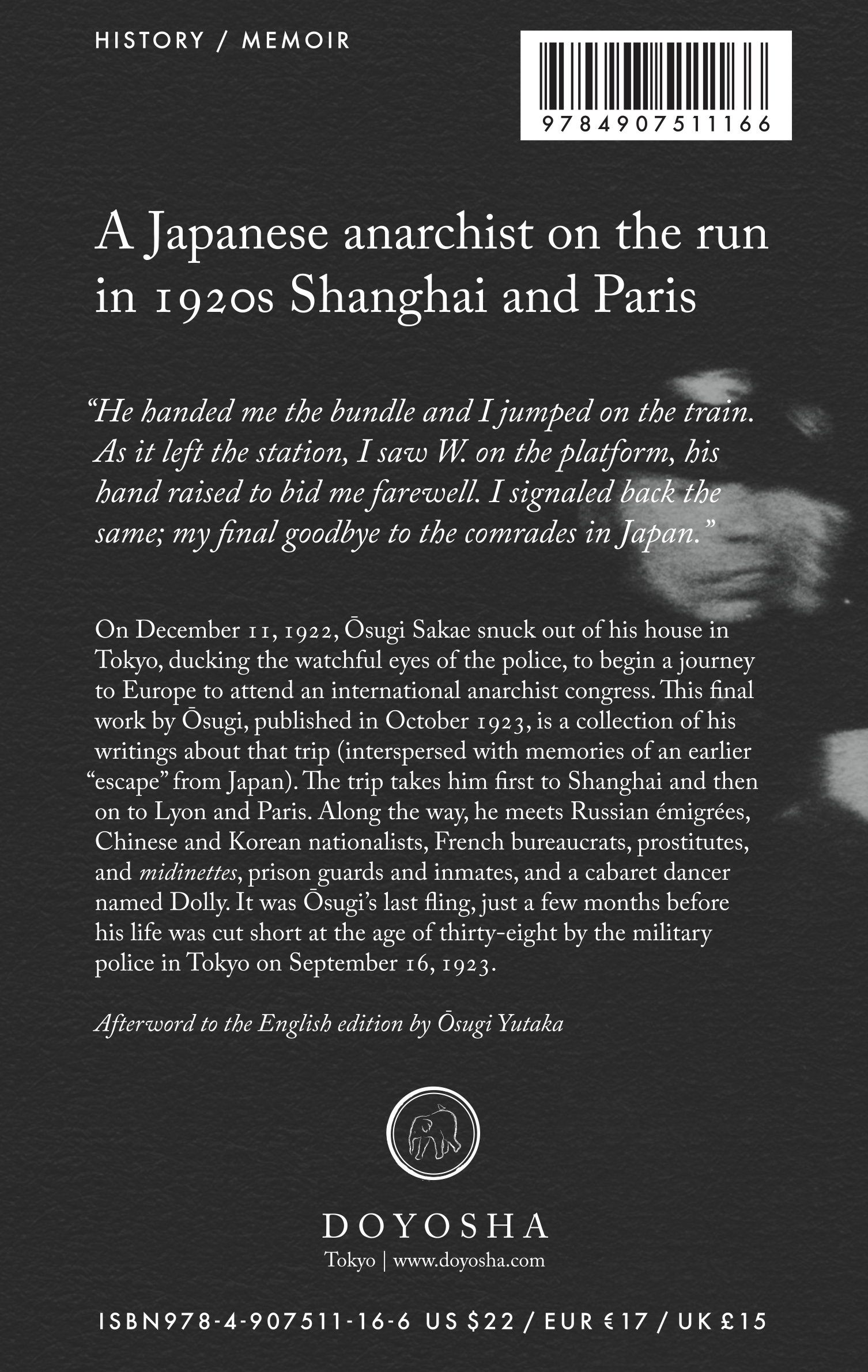

Written: April–September 1923

Published: October 1923, ARS, Tokyo

Translation: Michael Schauerte (from Japanese)

Source: My Escapes from Japan, Doyosha, Tokyo, 2014

HTML: Michael Schauerte

This translation is licensed by the copyright owner, Michael Schauerte, exclusively to MIA. Publication on other online sites is prohibited.

I had anticipated that my overseas itinerary would include a stopover in prison at some point, and in Paris that moment finally arrived.

I had anticipated that my overseas itinerary would include a stopover in prison at some point, and in Paris that moment finally arrived.

Getting locked up is nothing new for me. But I hadn’t expected it to happen in Paris.

In Japan before my departure I didn’t have the chance to meet anyone just back from Europe, but in China I did encounter several people who had returned from France. They all reassured me that once I crossed over into France everything would be fine.

I learned from them that even without a passport I wouldn’t be stopped en route or when I disembarked in Marseille.

I happened to have a rather good fake passport. The nationality and name listed were not mine, but the photograph was of me, wearing the same clothes I had brought for the trip. I felt confident that the authorities would not spot it as a fake. And in fact the French consulate and the English consulate each issued me a visa right away on its basis. After all the trouble I had gone through to get that passport, I did not plan to cross the border without showing it.

My worries en route concerned other matters; ones that could not be solved beforehand. And any mistake on that count would leave me no choice but to give up.

But everything went smoothly in the end, and I felt, as I had back in Japan, that once I crossed over into France my problems would be behind me.

This expectation seemed to have been confirmed when I went to get my visa at the French consulate. I handed over my passport to the clerk and, just when I thought he was taking it somewhere else, he came back and issued me a visa as soon as I paid the handling fee. The rather indifferent way he carried out the transaction surprised me.

On my way to France I heard a lot about how free the country was.

“Wait until you get to France, then you’ll know what freedom is all about.”

That’s a line I recall from a conversation I had with “Madame N.,” a former student at Moscow University who spent several years studying in Paris. She had been forced to leave Russia when her brother’s connection to the Social Revolutionary Party made her suspect in the eyes of the Czarist bureaucracy. Later she spent quite some time in Japan. We happened to be traveling to France on the same ship.

“When you first arrive at a hotel in France, be sure to present your business card, whether genuine or a fake,” she advised me. “As long as you show someone your card, you won’t get any other questions. That would never work in Japan or Russia, of course.”

But soon after we disembarked in Marseille, Madame N. had an experience at a hotel that punctured her belief in French freedom. The man at the front desk pulled out a type-written form that he asked us to fill in. A closer look revealed it was a detailed register, requiring far more information than those in Japan.

After exchanging glances, Madame N. and I each filled in the information until we came to the part that asked us to list our carte d’identité.

“What’s this all about?” I asked her.

“I was wondering the same thing,” she said, laying down her pen for a moment.

“If you don’t have your carte d’identité, a passport is fine,” the clerk told us. I wasn’t sure what he meant at first, but then realized I could just write down my passport number. Afterwards, the man then led us up to a room on the second floor.

This one little altercation clouded Madame N.’s expression, although neither of us yet knew what a carte d’identité was.[1*]

The next day Madame N. and I bid each other farewell. [2*]

I went to Lyon, where there were a number of comrades of the same nationality listed on my passport. I was carrying letters of introduction to them from the comrades in Shanghai. I wanted to make sure that I didn’t cause the Lyon comrades any trouble, since I was traveling in Europe under the same nationality.

Anxious to be on my way to Paris, I told the comrades that I wanted to depart Lyon in a night or two but could come back to spend more time with them later. They advised me, however, to stay.

“It’s more convenient here, with so many of us around,” one of them said. “Set up residence in Lyon and get your carte d’identité, then you can travel wherever you like.”[1]

I was on a visa that only allowed me to travel from China to France; a separate visa was required to visit any other European country. I was also required to have a carte d’identité, which any foreigner residing in France for more than two weeks had to obtain from the police. Without this identification listing one’s place of residence, a foreigner risked arrest at any time, as well as a prison sentence and deportation if there was no valid reason for not having it.

“It’s basically a dog collar,” one comrade (whom I’ll call “A.”) said, pulling out of a pocket his own identification papers with a photograph attached. The document required two French guarantors and two others from your home country, and even the birthdate of both parents.

The process of obtaining the carte d’identité generally takes a week. During my wait I had hoped to attend a meeting of some French comrades that I read about in the newspaper. But when I asked the Chinese comrades to accompany me, comrade A. and the others refused. They explained that I would be taken into immediate custody if I attended the meeting, not only ending my chance of getting a carte d’identité but making it impossible to obtain a passport to travel in Europe – and perhaps even placing myself in peril.

Those experiences gave me a clear sense of the political reaction that had settled upon France after the war. Far from being a safe haven, the country seemed fraught with dangers flickering in front of my eyes.

The carte d’identité was shaped like a pocket-size notebook. On the back page was a space for listing information on departures, arrivals, and repatriation. Whenever you departed your place of residence, you had to visit the police to have this page stamped.

Ignoring that rigmarole, I headed straight to Paris to visit l’Union anarchiste, whose office in Belleville was under heavy surveillance (as I described in “Escaping Japan”).

When I checked into a hotel near the office, the proprietor asked me not only to sign the hotel register but also to show my carte d’identité.

These bureaucratic hassles were making me feel more ill at ease. I decided to visit some other Chinese comrades on the outskirts of Paris and further out in the countryside, joined by the Chinese comrade[2] who had accompanied me from Lyon. After a few days, the two of us returned to the hotel in Belleville that an Italian comrade had introduced to me. This comrade had been staying at the hotel herself, but we returned to find her making hasty preparations to move on to another place. She told us that the intrusive police presence was driving her away.

The Chinese comrade chose to head back to Lyon right away. And I decided to find a safer place myself, relying on the Italian comrade for help. That evening the two of us went to the headquarters of the CGTU[3] to attend a popular musical concert hosted by le Libertaire, only to find almost a dozen uniformed policemen standing guard outside.

On the following day, when I visited the Libertaire, I encountered an emaciated man with a shaggy beard and long hair. He was on the verge of collapse and could barely speak. We learned that he was a Hungarian comrade who had been thrown in prison there for six months because of his anti-militarist activities. Just after his release the man fled secretly to France, but there he was arrested again for lacking a passport. The day we saw him he had been released after three months in prison and was about to be deported.

That same evening I visited a young Russian comrade whom I had been planning to meet for some time. There was no reply at his apartment, though, even after I knocked on the door several times. I thought he must be out, but when I gave the door once last knock a trembling voice inside told me to wait a moment. Finally, the door opened and the comrade plunged into my arms after recognizing my face. When I asked what was wrong, he said that he had been bracing himself for arrest, certain the police had arrived. He had no passport and had fled Russia to Germany, and from there to France.

The comrade told me he was heading straight back to Germany. It made me realize that in a country as vigilant as France I had little choice but to hide out. The situation seemed somewhat better in Germany, so I resolved to make my way there as soon as possible, especially since the international anarchist congress was supposed to convene in Berlin on the first of April. I was willing to risk arrest at the congress, where I would have to reveal my real identity, but did not want the authorities to get hold of me before then.

It was around this time that my Japanese friend S.[4] paid me a visit. My strict policy since leaving Japan for France had been to avoid contact with other Japanese, but I made an exception for S. and told him confidentially that I was in Paris and where I was staying.

Once S. had been apprised of my situation, he suggested that we find a new place to stay together, since he had decided to return to Paris from the countryside. He went out to look for a suitable hotel, and we ended up staying at the place he found.

“Since you can’t risk going to any political gatherings or visiting many people, we might as well set up camp in the city’s biggest playground,” he suggested.

That was our reason for choosing a hotel right in the heart of Montmartre. And we proceeded, as planned, to enjoy ourselves day and night. During this time, I was awaiting word from the Lyon comrades, who were to notify me as soon as a new visa was issued that would allow me to travel elsewhere in Europe. The plan called for me to then return to Lyon and prepare straight away for departure to Germany.

A week or so later, just as I was settling into my new life of pleasure and the fun was getting underway, a message did arrive from Lyon, but it coincided with some rather alarming news. I learned that the Japanese government had wired its embassy in Paris to order an immediate investigation into the conduct of S. And I took it for granted that the investigation would turn up my own whereabouts as well.[3*]

S. and I had used up our money by then, but we managed to borrow a bit more and beat a hasty retreat from Paris.

S. returned to his old place in the countryside, and I went back to Lyon. At police headquarters there, I requested permission to travel to Germany, making no mention of all the other places I had visited in France. Until I received that permission, it was pointless to request a visa at the German consulate.

S. returned to his old place in the countryside, and I went back to Lyon. At police headquarters there, I requested permission to travel to Germany, making no mention of all the other places I had visited in France. Until I received that permission, it was pointless to request a visa at the German consulate.

The office of the Police des Étrangers, which issues visas, was located in an old courthouse building, a bit removed from police headquarters. The officials there told me it would take four or five days to handle the paperwork, and that if I stopped by the same day the following week everything would certainly be ready. With the matter apparently settled, I fixed my departure date and got my preparations fully in order. While waiting, I read through a few recently published books on Germany and recited passages from a German primer. I even bought a book to learn Italian, since my plans included a stopover in Austria, Switzerland, and Italy on my return.

But on the awaited day, a week later, the officials informed me that my papers were still with the passport section, also located in the courthouse building. An official there told me that my papers had been passed along to Sûreté Générale, the investigative branch located in the same building. But when I went to their office, once again I was told to wait a couple more days until notified. It was all terribly annoying, but my only choice was to await that notification.

A couple days went by with no word. By the fourth day I had lost all patience and went to find out what was happening. I was told that the notification had been mailed the same day, and that I should return with it tomorrow.

On the following day, the Sûreté Générale officials investigated various points. First they asked me about obvious things that should have been clear from the passport and identification I presented for my application. Then they set about prying into every sort of detail regarding my activities since arriving France and the purpose of my trip to Germany. I answered the questions more or less coherently, but my biggest problem was that they also examined the details on my identification card. My parents’ names and dates of birth were all fabrications, as was the information on the two guarantors in the country. Keeping track of all these lies was not easy, but somehow I managed.

What I did not manage was to find out when I could receive the permit for which I had applied. First they told me to return in two days, but when I did the message became, “Come back on the day after tomorrow.” I did as I was told, thinking it would surely be ready this time around, but again was asked to wait another day. The next day it was “the day after tomorrow” and so on like this, as each time I was asked to wait another day or two.

The police checked up on the proprietor of the place where I was staying three or four times and also looked into various matters regarding S., who had spent a night there, too.

Feeling increasingly nervous, I considered giving up on the legal procedures and just crossing the border clandestinely, as my Russian comrade had done. Since arriving in France, I had debated the Lyon comrades over this issue of legality. My view from the start had been that it was better to dispense with the bothersome carte d’identité and just travel around as I liked. But I reluctantly went along with their above-board approach, not wanting to create trouble for these comrades who had taken care of me. And now, once again, I was playing by the rules.

That’s why I spent an unpleasant and worrisome month and a half of stopping by police headquarters almost every day.

I was fed up with waiting.

The congress had been postponed again. The basic plan now was to convene it in August, rather than the first of April, but it was not clear whether it would ever be held. The German comrades were saying that it was impossible to gather in Berlin. Some other place in Europe had to be found. But where? Some suggested Vienna, but that was also thought too risky.

As my time was being frittered away, my money also ran out. To make matters worse, I caught a cold and the medicine I took for it did my stomach in. Without even a centime, I spent a week in bed, barely eating anything.

Around the time I finally roused myself from bed some unexpected money arrived. It was also time for my regular bureaucratic appointments in Lyon. I was proving no match for the officials’ way of putting me off another day or two with some excuse and the customary French shrug, always claiming to have no precise knowledge of the matter. The slight shrug and smirk annoyed me to no end. I invariably returned from such visits in a foul temper.

Spring had arrived in the meantime. Each day new leaves appeared on the chestnut and sycamore trees that lined the streets of the hilly suburb where I was staying. The colors were light green, with none of the darker colors mixed in that you see in Japan. Interspersed among the trees were red and white patches from the pear and cherry blossoms, and in between the branches I could see the reddish-orange roofs and walls of the houses on the other side. Everything was so bright and buoyant, almost unnervingly delicate, but the scene failed to raise my spirits.

And the rain kept falling down.

May Day was approaching. I had more or less given up on traveling to Germany. I decided to quietly make my way to Paris to see for myself what May Day was like in the city and check up on the month-old midinette seamstress strike. I also was keen to attend the sorts of meetings that I had been avoiding until then and gather some needed research materials. Plus I wanted to see the tree-lined streets of Paris in their spring foliage and observe the faces of the Parisian women.

On the evening of April 28 I departed Lyon, only telling one comrade where I was headed. Upon arriving in Paris I stopped by the Libertaire office to see Colomer.[5] We promised to meet again at the May Day gathering in Saint Denis.

The authorities had banned outdoor meetings and demonstrations on May Day, and the workers had no plans to hold such activities in defiance of the ban. Communist politicos and CGTU leaders were careful not to rock the boat, fearing a clash with the police.

Even the plans for indoor meetings were limited. As far as I could tell, the only major gathering in the center of Paris was to be held at CGTU headquarters. All of the other events were planned for suburban working-class districts. A scheduled march to the American embassy to protest the death sentence handed down to Sacco and Vanzetti, our Italian comrades, was also moved outside the city at the insistence of the communists.

The May Day meeting in Saint Denis was expected to draw a crowd. This suburb north of Paris, a center of iron production, was known for its revolutionary minded workers. Colomer was to address the meeting in Saint Denis as the anarchists’ representative.

I headed out early on the first of May to get a feel for the atmosphere in the city. What I encountered was just an ordinary day, more or less, only a bit more forlorn than usual, with not a taxi in sight.[6] All of the shops were open. The trains and subway cars still ran, packed with workers who were slightly better dressed than usual and accompanied by their wives and children. To my eye they certainly did not seem to be on their way to a May Day gathering on the city outskirts.

“Hey there, it’s May Day, no?” I asked a worker next to me, using the working-class argot I had picked up. “Where are you off to?”

“Ah, thanks to the holiday we’re going out to the countryside,” the man answered breezily, one hand around the waist of his not very attractive wife, the other gripping a basket full of sandwiches and wine.

I had to clench my fists to resist the urge to box the man across the ears.

The May Day handbills of the CGTU plastered on the walls were all torn or peeling off. Next to some were CGT handbills bearing the warning that, “May Day participants are German spies!”

The doors to the workers’ hall in Saint Denis[7] opened at three in the afternoon, and soon it was nearly bursting with more than eight hundred workers.

The speeches began. The scheduled speakers took to the podium, one after another, delivering long, grandiloquent speeches that touched on the slogans of the day: End the Ruhr occupation; Down with war; Amnesty for wartime political prisoners; Worker solidarity. The applause began to wane; yawning faces could be seen. More than a few even exited the hall.

Occasional shouts could be heard from the crowd: “Enough talk! Everyone, outside!” The shouts were coming from the anarchists who had been hawking le Libertaire and la Revue anarchiste outside the hall. But no one else was echoing the call. And often someone from the stage would descend into the crowd to stifle the protest.

Colomer and I had planned to head off somewhere for a meeting after his speech, but it all seemed rather pointless by then. My only desire was to get behind the podium and urge the crowd to go outside.

Right before Colomer rose to give his speech I called him over to ask if I might briefly address the hall after he had finished. He conveyed my request to the chairman (probably a Communist Party official), who came over to find out what I wanted to say. I knew that whenever communists and anarchists participated in the same event, each speaker had to promise what would be said in the speech. I told the chairman that I wanted to say a word about May Day in Japan. He had no idea of my name or who I was exactly, since Colomer had simply introduced me as a “syndicalist.”

While Colomer was giving his speech, I jotted down notes for my own address, then took my place on the platform as he was wrapping up. Colomer said something about Germaine Berton, the female anarchist who had assassinated a royalist she thought responsible for the Ruhr occupation. And this brought out encouraging cries of C’est ça, C’est ça! from a teary-eyed woman near the stage who was around forty years old and looked like a worker.

My own speech, as I had promised the chairman, described May Day in Japan.

“The history of May Day in Japan doesn’t go back very far,” I began. “And not many workers participate yet. But Japanese workers all know about May Day. It’s not celebrated on the outskirts of Tokyo but right in the city center. And it’s not held inside, with speeches delivered in a hall, but outside, with demonstrations in the parks and public squares. May Day in Japan is not some sort of festival. ×××××. ××××××××××××××××××××××××××××.”[8]

“×××××××× fly out. ××××××× shine.”[9]

My somewhat exaggerated explanation of May Day in Japan lasted twenty or thirty minutes, interspersed by the sight and sound of the woman near the stage, urging me on with her cry of C’est ça, C’est ça!

I stepped down from the platform – amid shouts of Dehors! Dehors! – and was trying to make my way outside when I was confronted by a handful of plainclothes cops who ordered me to come with them.

Soon policemen had surrounded me. Without much trouble they seized my arms and legs and began to drag me away.

Not too long after, at the police station where I was taken, I could hear a crowd out front singing “The Internationale” and shouting.[10] A herd of policemen who had been lurking in the courtyard of the station sprang into action to confront the crowd as I was taken away, further into the building.[4*]

I didn’t reveal my name or nationality to the police, and insisted that I had no passport or identification. Their other questions also yielded scant response from me.

Colomer soon arrived in the hope of securing my release. He advised me to tell the police the name[11] printed on my passport. The chairman of the gathering arrived soon after with a couple others. All agreed that the matter was trivial, and that I would be released if I just told the police my name.

Waiting for the right opportunity, I took a small notebook out of my pocket and slipped it into the chairman’s hands. The notebook had been taken from me by the police, but in the commotion that followed the entrance of the chairman and his comrades I had managed to pocket it again. When my interrogation began a plainclothesman realized the notebook was gone and accused me of taking it. I stubbornly insisted that I didn’t know what he was talking about. Another chimed in that he had seen me hand something to Monsieur So-and-So (the chairman) and asked his partner if he should go retrieve it.

“He doesn’t have it, eh? Must have slipped it to someone,” the first cop said, somewhat resigned to never getting the object back. The other policeman, after raising some sort of objection, went off. A little while later he came back with the notebook in hand, much to the pleasure of his colleague, who started to flip through it.

If they examined every page thoroughly, somewhere they would uncover the false name I was using. Or at least they would come across things I had jotted down to remember some of the nonsense for my carte d’identité application, like the names and ages of my fictional parents. In any case, they were sure to come across all sorts of leads. My hope had been to tear up the notebook and flush it down the toilet – and with that aim in mind I had asked for a drink of water right after the police dragged me to the station. I was allowed to use the toilet a bit later, but a policeman came to check up on me when I was still trying to get rid of some calling cards and other papers inside the notebook, leaving me still holding it.

Having no other option, although still thinking it too soon, I decided to follow everyone’s advice and give the police my (false) name. I said I was XY from country YZ and that my passport and carte d’identité were at police headquarters in Lyon pending permission to travel to Germany, as was in fact the case. I told the police I was a journalist and described my politics as “syndicalist.” As for why I had introduced myself as a Japanese at the meeting, I said that that I was familiar with Japan, having lived there for many years, and thought it would be more effective to claim citizenship if I was going to talk about the country.

I thought they might let me go after I divulged these facts, but at this point the situation was out of my hands.

It was already evening by the time the initial investigation ended.

Once the plainclothes officer left the interrogation room, a handful of tough-looking uniformed cops appeared, slapped handcuffs on me and led me away.

I thought they were taking me to a jail cell, but instead they led me to the entrance, where a large delivery truck was waiting with around ten officers. Using excessive force, they threw me into the back of the truck, then the officers hopped in and the truck sped away.

It was pitch black inside the spacious cargo area in the back. I was sitting cross-legged in a corner, both hands bound, policemen clutching my arms and shoulders.

Occasionally I could see the faces of the cops from the glow of their cigarettes. They did not look very European to me – more like savages from a French colony in Africa or the offspring of French soldiers stationed there. They seemed tense, as if they had just come from a fight, and were shouting something I couldn’t make out.

After a while the cop holding my shoulder began to poke me, growling like a bear. Seeing that things might get rough, I removed my glasses and placed them in my pocket. But when the cop in front of me saw that, he hissed like a fox and struck me in the face.

Along with the blows that rained down on me was a torrent of snarls – like a monkey, bear, or fox might make – interspersed with some French that sounded to my ears like:

“I’ll kill this bastard!”

“Where does this Chink think he gets off.”

“German lackey!”

One even went so far as to remove a pistol from a bag and jab me on the head with it, and then do the same with an unsheathed sword.

Not long after, though, the truck stopped, for we seemed to have reached our destination. Half of the policeman dragged me from the front, while the other half struck and kicked me from behind, forcing me into a building. I was still in Saint Denis, just at a different police station. The policemen took me to a spacious room near the entrance, where they again pounced on me, tearing off my necktie, belt, and shoelaces before throwing me into a cell at the back of the room. There, with my clothes still on, I fell into a deep sleep.

Early the next morning two detectives arrived to take me to police headquarters, this time in a regular automobile.

They interrogated me there throughout the day, asking the same sort of questions as the day before. When I kept quiet about the hotels where I had stayed in Paris, a few policemen ushered me into a car that took me to each of the hotels, where the proprietors identified me. The police had known everything all along, I discovered.

I was brought back to headquarters, where I found a large room had been prepared for me, next to the Police des Étrangers office. A man who seemed to be the section chief greeted me.

“Monsieur Ōsugi, if I am not mistaken?”

He’d hit the nail right on the head. If they knew this much, it would be easier just to tell them whatever else they needed to know.

The inspector left the room for a moment on some errand, and one of the plainclothes detectives from the car entered.

“You might be pleased to know that there was quite a May Day in Japan,” he said, pointing to a short article in the Communist paper l’Humanité. Under the headline “Dozens Injured,” was a one-column article on the incident involving me at Saint Denis.

The article made no mention of my real name. I found out later that the police discovered my identity after someone from the Japanese embassy or somewhere else inquired if the man referred to in the article might be me. I also learned at some point, although I can’t remember when, that an official from Japan’s Interior Ministry and from Hyōgo Prefecture had been sent to Paris to find me.

The plainclothes cop, still quite young, was kind to me in many ways. When the tobacco I’d purchased on the way there ran out, he handed over a pack of his own rather harsh French cigarettes. And he advised me that if deported on the border with Spain I should make my way to Barcelona, rather than Madrid, because I would find more comrades of my political persuasion there. He even looked up maps and train schedules to show me which way to go and how long it would take.

But a couple other plainclothes cops took turns watching me too, and one was a right bastard. I recall him saying something like:

“They must have paid you quite a lot for you to come all the way from Lyon to make a speech.”

He drew very near me as he spoke and vulgarly fingered a large scar near his mouth, probably a war wound.

“You must have bought this in Germany, huh?” he said, handling a knife with a “Made in Sheffield” label that I had purchased in Singapore.

He kept on like this, picking over my belongings and implying that each had been bought in Germany. In his eyes, it was all proof of my guilt. He thought that the German government had paid me to stir up the workers in France.

“Look,” I said to him at one point. “I’m not going to bother talking to anyone who spouts such nonsense.”

This enraged him. “You Boche bastard!” he shouted, shaking an enormous fist in front of my face.

“If you’re going to hit me, get on with it,” I said out of irritation, and braced myself for the blow, but at that moment the friendlier detective entered and led my tormentor to another room.

Now that my real name was known, the investigation was easily concluded. Another detective took me to the fifth or sixth floor of a different building, where I was stripped to undergo a physical examination and be photographed.

In Japan the police were content to simply measure height and weight and take a person’s fingerprints. But the French, true to form, adopted a more scientific approach. Like anthropologists, they determined the size and length of my skull, and measured the length from my outstretched fingers to my forearm. A special chair was used for the mug shots, so that after the profile was taken it swiveled around easily for the frontal shot.

After all this had been done, I was escorted to another building for my preliminary hearing. Once this very cursory court proceeding was over, I was brought back to the same building as before and placed in a cell. All of my possessions were confiscated, but I was allowed cigarettes and matches.

I stretched out on the bed at once, admiring those two objects, and enjoyed a smoke before drifting off to sleep.

I must have been rather tired, but also it has long been my custom to lie down and sleep whenever I’m tossed into a jail or holding cell.

The next morning, the third of May, I was transported along with around fifteen comrades (?) to La Santé Prison in two large horse-drawn wagons.

La Santé is a detention center, famous for holding political prisoners. At some point on my voyage to France, I don’t recall exactly where, I heard over the wireless from France that Cachin and a dozen other Communist Party leaders had been detained at the prison. I figured they might still be there. Soon after I arrived in France, a dozen or so anarchists were also sent to La Santé to join the other anarchists already there.

The guards brought me some more cigarettes and matches. Unlike in Japan, where each inmate carries back to his cell one of the futons laid out in the area where the six wings of the star-shaped prison intersect, at La Santé we were handed a dingy nightshirt and a hand towel of sorts.

Entering the prison put me in an inquisitive mood. As a guard led me down a wide corridor, I looked all around at my new surroundings.

He placed me in cell number 20, on the ground floor of holding block 10. The square cell was just around eight tatami mats in size,[12] with a large window that let in plenty of light. The window was some five feet wide at its base and about the same height, the top two feet arching into a semi-circle.

None of the hotels where I had stayed up to then, apart from a few elegant exceptions, had such a magnificent window. And it was all the more impressive considering that the base of the window only began at eye level.

Later, when I went out to the yard for exercise, I saw that the large windows were only on the ground floor, whereas the windows on the three floors above were just half the size.

From the window I could see the tall prison wall nearby and above it the branches of three chestnut trees, the white flowers already in bloom.

To the left of this westward facing window was a small bed attached to the wall, covered with a woolen blanket. I sat down on the bed and found that its spring mattress made it quite comfortable, and the blanket was nicer than the one at my boarding house in Belleville.

To the right of the window was a table, also attached to the wall, with a proper wooden chair placed under it.

On the wall to the left of this table, near the entrance, were two hanging shelves on which a bowl, a wooden spoon and fork, and other utensils were placed.

And on that same wall, facing the entrance, there was a water spigot in the corner, near the foot of the bed, below which was the large opening of a white porcelain toilet. This was the only slightly irritating thing about the room, as it meant you had to wash dishes right above the toilet.

The floorboards were an imitation mosaic, the little pieces of wood placed in a rather stylish zigzag arrangement.

This must have been what Anatole France’s fictional character Jerôme Crainquebille, a vegetable peddler arrested by the police, meant when he said that the floor of his prison cell was clean enough to eat off of. In Paris, I watched a moving picture[13] based on the novel, with a scene that showed Crainquebille just after he entered prison. I was struck by how happy he seemed as he looked around his prison cell.

I felt terribly fond of my own prison cell from the moment I set foot inside. After having a look around and trying out the springs on that comfortable bed, I stretched out and lit myself a cigarette.

After a while, a prison guard brought two half sheets of printed paper from the canteen and affixed them to the wall above my table. Under the heading “Provisions and prices” in large print was a column listing “Consumable goods” and another listing “Food,” along with the price of each item.

All sorts of daily goods were available: ink, paper, pens, hairbrushes, toothbrushes, sponges, hair cream, towels, cigarettes and cigars, leaf tobacco, along with around twenty things to eat, including bread, steak, roast beef, sausage, omelets, ham, sardines, macaroni, salad, coffee, chocolate, butter, jam, sugar, salt, and rice, as well as various fruits and wine and beer.

Each week a menu was also handed out to inmates listing some of the rather tasty-looking selections available from the canteen for breakfast and dinner. And, if the servings were not sufficient, we were allowed to order extra dishes to supplement the evening meal.

Restrictions were placed on items available to convicted felons (although no one in my cell block had been convicted yet). For example, an inmate might only be allowed meat three times a week, or wine and beer consumption might be limited to sixty centiliters a day.

After looking at the lists posted on the wall, I knocked on the door to summon the guard and ordered some things. When I requested to have my meals brought every day, he asked:

“Do you want meals from our restaurant or from the outside?”

The guard looked like an ex-soldier, with a sturdy face and body, the smell of wine always on his breath; yet he seemed surprisingly fond of people. He spoke in a strange French accent that required my full attention to arrive at some understanding. I told him that I would prefer ordering from an outside restaurant, figuring it would taste better.

A bit later a young waiter from a restaurant outside the prison arrived to show me a small menu and take my lunch order. There were a dozen or so dishes on the menu. I chose four and made the extravagant request for the best white wine they had, and the waiter headed back to the restaurant with my order.

All of this had put me in a fine mood. It seemed that I would only need the equivalent of forty or fifty yen a month to enjoy quite a pleasant stay.

When the order arrived, I had a few sips of the wine and made short work of the food, even polishing off some chocolate for desert. Then I climbed back into bed and puffed away at a cigar. My thoughts turned back, not for the first time, to home.

Word of my arrest probably would have reached Japan by now through the newspaper wires. None of my acquaintances would be particularly surprised by the news, but the children – especially my eldest daughter, Mako – would no doubt be worried by the way the adults were acting, even if no mention of my arrest were made.

My wife told me in a letter that when Muraki,[14] who was staying at our house, was wrapping a book to send to someone, Mako asked him softly: “Aren’t you going to send Daddy anything?” When we sent her off to stay at a friend’s house so she wouldn’t notice my departure, she was sure I was going to be arrested. Whenever Mako asked where I was, the response was either silence or a change of subject. Sometimes at night, alone with her mother, she would speak casually about the rumors surrounding me. Knowing what Mako must be feeling, I thought I should send her a telegram. I sat down at the table and wrote a number of simple messages, but did not come up with anything that could be sent inexpensively as a telegram. After those attempts, I jotted down an odd little thing:

Mako, sweet Mako!

Papa’s now in La Santé

A world-famous

Prison in Paris.

But don’t worry, dear Mako

I feast on French meals

Savor chocolates

And puff-puff my cigars on the sofa

Cheer up Mako!

Thanks to this prison stay

Papa will soon be home

Just wait a little longer

You’ll see me soon with my

Load of presents and kisses

For my baby girl.

I took to reciting this jingle in a loud voice while lounging about my cell all day long. The strange thing was that, even though I wasn’t the least bit sad, tears began to stream down my face when I chanted those lines. My voice trembled as the tears flowed.

I should mention that I did not always feast so well in La Santé. At first it seemed I would have more than enough money to spend two or three luxurious months in prison, having just received a payment from Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun for a newspaper article[15] I wrote before my arrest. But near the end of the first week in jail, a guard informed me that I had little money left because most of it was seized by the court on the suspicion that it had been supplied by Germany.

This left me with no choice but to eat the standard prison fare for the time being.

At around eight in the morning a loaf of black bread about the size of a child’s head was slipped through the food slot of my cell. I could only manage a couple bites of this cold and crumbly, tasteless bread that was not just black but charred.

In all my time spent in the slums of Belleville, where I bought bread at a local bakery for the meals I cooked, I never once came across a loaf of black bread. And I doubted that anyone in Paris ate such stuff.

In the early afternoon the loud cry of “Soup!” could be heard in the prison. This soup, as it was called, was brought to us on a rattling cart. We were handed an aluminum bowl filled with slightly discolored hot water seasoned with salt. Beads of viscous oil glistened on the surface, while scraps of carrot and cabbage settled at the bottom of the bowl.

One look at this soup on my first day in prison was enough to know it wasn’t for me.

A couple hours after the soup, another bowl of food was brought to us. There were stewed beans one day, and boiled potatoes on another. I liked beans and potatoes, so from the beginning I didn’t turn them down. On a different day I was brought rice gruel with quite large pieces of meat mixed in. But the meat was so tough that I had to spit it out after a failed attempt to chew it. That gruel with rice was brought twice a week.

That was roughly the extent of the culinary delights in prison.

At first I could not get much of this food down, but my hunger drove me to manage eventually. By the end, I was able to wolf down a whole day’s worth of black bread right after it was handed over to me, and polish off every bite of the afternoon bowls of food as well. But even so, I felt hungry. And they didn’t bring me water, so I had to guzzle it from the tap in my cell.

The day after I entered prison a letter arrived for me from Henry Torrès,[16] a rather famous lawyer for the Communist Party who also defended revolutionaries from other political tendencies. This lawyer, whose name I’d heard spoken of before, was assisting me at the request of Colomer.

“You should inform the investigating judge that I have taken up your case,” the letter from Torrès stated. “If a preliminary hearing is called suddenly, make it known that you are unable to answer any questions unless in my presence.”

The letter had arrived in a sealed envelope that I was the first to open. That struck me as odd, but even more interesting was his reference to, “unless in my presence.”

I immediately wrote a letter to the judge and another to Torrès, only sealing the envelope for the former. When Torrès later met me to discuss the case, no prison official was on hand to supervise. We could speak freely and hand over to each other whatever we liked.

A prisoner was thus in a position, provided he had enough money, to create false evidence or destroy actual evidence. A thief could use his stolen money to hire a lawyer and free himself of a criminal charge, or even set about some money-making scheme in prison to cover his legal costs.

Every day I lounged about in bed since I was no longer able to buy food or tobacco and had no books to read. It was astonishing to discover just how much I could sleep.

I thought that dozing in the middle of the day might be frowned upon, but I decided to do it anyway until someone scolded me. Unlike the situation in Japanese prisons, the guards rarely stopped by my cell. One would stop by after I woke in the morning to open the cell door and remove the trash without issuing any signal or command to me. After taking a look around the cell, he would then escort me to the prison yard. Apart from that, no one came around except for the three times when meals were slipped through the slot. We were spared the sort of morning and evening inspections common in Japan. A guard did peek in the cell in the evening upon replacing the afternoon guard, but that was about it.

This left me without any feeling that I was under observation. I was truly living a quiet life on my own with no one to bother me. Apart from sleeping, I did occasionally get out of bed to stroll around the cell.

On those rounds I kept my thoughts carefree by reading the messages scribbled on the walls. Most messages followed a similar sort of pattern, like:

René de Montmartre

tombé pour vol

1916

The name might be Marcel or Maurice, instead of René, but most hailed from Montmartre, Montparnasse, or some other Parisian den of vice – similar to the Honjo or Asakusa districts in Tokyo. The scribblers also liked to write their nicknames underneath.

dit l’Italien

dit Bonjours aux amis

There were all sorts of nicknames, although I’ve forgotten most of them. I do recall that one prisoner in for murder went by the name “Iron Arms.” Other prisoners were pining for their date of release:

Encore 255 jours à taire Vive décembre 1923

Another short message that I recall was about hitting an unlucky number:

Ah! 7! Perdu!

Alongside it was a drawing of a pair of dice, with the numbers three and four showing.

And then there were passionate messages of the kind you’d never see in Japan.

Riri de Barbes

Fat comme poise

Aime sa femme

Dit Jeane.

Or:

Emile Adore sa femme pour la Vie.

And another message, signed “A Bolshevik”:

Ce qui mange doit produire

Vive le Soviet

For a bit of fun, I took out my pen and wrote on the wall in thick letters:

E.[17] Ōsugi

Anarchiste japonais

Arreté S. Denis

Le 1 Mai 1923

I was summoned for my preliminary hearing.

The questions started before my lawyer arrived, so I immediately adopted the customary stance of hunching my shoulders and not saying a word. The court quickly ordered a clerk to go find my lawyer.

The proceedings turned out to be quite simple, mainly involving a chat between my lawyer and the judge.

A long list of criminal charges against me had been issued by the Prefecture of Police: Defying a government official by violently resisting a police officer; Disturbing public order; Violating passport regulations; Vagrancy. But the preliminary hearing only investigated the passport violation charge, perhaps because it was the easiest crime to prove.

At one point the judge asked me quite politely – although I don’t know how he uncovered the information – whether my father was indeed a colonel in the Japanese army. My father was only a major, in fact, but I offered no correction since the judge had made such a point of mentioning it. He seemed to pay me a fair amount of respect, perhaps because the conservative dailyL’éclair had published an article by a former socialist familiar with the movement in the Orient who described me as a “renowned scholar.”

In the initial discussion with my lawyer, the court said that a month or two would be needed prior to the trial to investigate various matters in Lyon. But when my lawyer requested bail at the preliminary hearing it was decided, after considerable deliberation, that the court case would be convened immediately in return for forfeiting the bail request.

My court case was held on May 23, a week after the preliminary hearing. Some fifteen other accused men were waiting with me in the defendants’ box, along with a crowd of spectators crammed into the gallery. A bell was sounded and three tottering old judges entered the courtroom, followed by the prosecutor. On the wall behind the judges was a sculpture of the goddess of justice, in white relief.

The court cases began with the head judge saying something in a toothless mumble that even those of us seated nearby struggled to decipher.

“The defendant did this (or that), on this (or that) day. Isn’t that correct? All right then . . .” he would say, looking in the direction of the prosecutor. And then, after receiving a nod in return, he would ask if the other two judges had anything to say.

The head judge proceeded to rapidly issue his verdict of so many months in prison and a fine of so many francs, and then summon the next defendant.

I was around the sixth in line, and my case proceeded just like the others.

“You, the defendant, entered France on such-and-such a date, bearing a false passport. Is that correct?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have anything else to add?”

“No, I do not.”

“So, you acknowledge the truth of the accusations?”

“Yes.”

That was the end of the questioning. The prosecutor seemed to have nothing to say and just nodded to the judge.

My lawyer then held forth in his eloquent way for twenty minutes, after which the judge intoned:

“Very well, then. I sentence the defendant to three weeks in prison and a fine of XX francs. Next defendant . . . "

After the judge pronounced his verdict a constable standing behind us approached and led me away.

In France, all but three days spent in detention prior to a trial count toward the prison sentence. So I had already served my three-week sentence by the time of the trial and could be released the following day.

The news came as a crushing disappointment.

Four or five defendants were kept in the detention cell of the courthouse prior to the hearings. During the wait, they were grousing noisily about their own cases. Each recounted whatever crime he had committed and speculated on what might be said in court to get off with a lighter sentence. In response, another might disagree, pointing to how saying such a thing would only backfire in this or that way. And yet another might say, “There’s nothing to worry about: you’ll only get three or four months, tops.” The talk was the same sort of chatter often heard in a detention cell outside a Japanese courthouse, mostly about money: how someone managed to get hold of a few hundred or a few thousand francs through this or that scam; utterly boring banter.

I didn’t say a word, using the time instead to inspect the graffiti on the walls.

A bas l’avocat official!

That line showed up in a couple places. Then there were the sort of messages I’d seen in my own prison cell. I found several professions of love written by a man who worshiped a lady in Bretagne, along with some rather good drawings of her. I even came across a few odd erotic sketches.

As I was carefully reading each message, I felt a tap on my shoulder.

“Hey there. What are you in for? Robbery?”

It was our resident expert on criminal convictions who had been holding forth with predictions on how many months his associates would be in for.

“Ah, well, something like that,” I responded coolly.

“Is that so? What did you steal? Are you from Indo-China?”

“No, I’m Japanese,” I said, thinking it less trouble to tell him the truth if he was so keen to ask questions.

“A Japanese thief? Don’t run into many of those. When did you arrive in France?”

The expert kept at his questioning, which I tried to cut short by being even more honest:

“Just after I got here the cops got me for making a speech on May Day.”

“Oh, so you’re in for a political crime,” he said abruptly and then turned to recommence discussion with his esteemed colleagues.

It was at that moment that another man, who had been among the others but only listening to them, came over to where I was. The man, around forty and with one hand that seemed a bit odd, began by saying: “They nabbed me, too, at the May Day demonstration at Place du Combat. Where were you arrested?”

The man looked like a worker; dressed in shabby clothes but quite well spoken. Place du Combat was a public space near CGTU headquarters. Many anarchists associated with le Libertaire had probably gathered there. I seemed to have found someone of a like mind, so I tried to find out more from him.

“They picked me up in Saint Denis,” I said. “What was it like at Combat?”

“There was quite a crowd. The ones I was with didn’t care much for the speeches, so we led a group that dashed off and smashed up a few cars and held up traffic.”

It turned out that he was an anarchist; a former factory worker who had injured his hand in the war. He did odd jobs to scrape together a living. The man told me that the year before there had been a riot at Combat, but that he and everyone else had escaped arrest. But this year the police cracked down. Even though the disturbance was no different from before, around a hundred protesters were arrested.

“The police played rough this time around, and my lawyer says the courts will come down hard on us too. I suppose you’ll just be deported, but I’m looking at six months behind bars.”

While I was talking to him, the time had come for us to be taken to the courtroom. When I returned to the holding cell later, the same man was there.

“Well, we’re both getting out of here,” he said. “I was handed a six-month sentence, as expected, but thanks to ‘His Honor’ and my lawyer’s persistence that was changed to a two-year suspended sentence.”

He looked pleased but let out a sarcastic laugh as he shook my hand. After a while, we all were taken out of the detention cell and transported to the prison.

The next morning, May 24, the police took us to the detention cell at the courthouse. They said they were going to place us in the Grand Salon, which turned out to be next to the other detention cell where we had been held before, with the same heavy iron door. And it was indeed grand: spacious enough to accommodate a lecture for five or even six hundred people. The courthouse and adjacent police ministry had once been royal palaces, apparently, and this room was some great hall from that era. The floor was cement, but there were several large marble pillars supporting a magnificent ceiling. Entering the room, I saw several groups of half a dozen men discussing one thing or another. I wandered toward one group of younger, more respectable-looking men.

They were speaking in French but something about their accent gave me the impression they were foreigners; their faces did not look very French. A tall, Italian-looking man among them glanced at me and asked right away:

“They’re deporting you as well, eh?”

When I said yes, he added:

“Ah, it looks like it. All of us, in fact. Care for a smoke?” he asked, holding out a cigarette case. We talked about all sorts of things, but nothing gave me the impression that these men had done anything particularly bad. Since they had landed in this prison and were now to be deported, I figured they must have been caught on some passport or carte d’identité violation. And judging from their lady-killer looks and demeanors, some of them must have made money pimping as a maquereau.

None of the men had the least intention of returning home to Italy, Spain, Portugal, or wherever they were from; nor did any of them plan to head off to some other country. No, they were all bent on returning to France – and to Paris, in particular.

“But if you’re deported, won’t you have to leave France,” I asked, finding their nonchalance a bit odd. “Not many of those ordered to leave actually do. We’re going to be called up and issued a deportation order. And that’s the end of the matter as far as the authorities are concerned. Where we go is our own business.”

This man seemed to find my own incredulity rather incredible. For two of the men, it was their second time to be issued a deportation order.

In my mind, “deportation” was a situation where a time limit is set to leave and in the meantime the police keep a close eye on you, as had happened to my Russian friend Kozlov in Japan. But it was nothing like that in France. It was reassuring to know that we were simply given a sheet of paper with the deportation order and then told to get out; and that nothing would happen to anyone (even a repeat offender) who simply ignored the order.

Finally they started to call out our names. One prisoner after another was summoned to be told which jail he would be sent to, until I was the only one left.

When my turn finally came, instead of being taken upstairs as the others had, I was led to the same small room near the entrance where my possessions had been examined at the time I first entered prison. My foreign friends of a moment ago already had their possessions and were on the way out.

“So, did they sort you out upstairs?” the handsome Italian prisoner asked me.

“No, not yet.”

“That must mean that you’re not being deported and are free to go right away,” the man said as he was leaving.

That did not seem to be the case, though, and I was feeling more and more anxious to be the only one left.

I was handed my things but not released. Soon after, another guard came to take me to police headquarters. There, my time was taken up, among other things, with the same physical examination I had undergone before, until finally, around midday. I was taken to the office of the deputy secretary, who handed me the order for immediate deportation issued by the interior minister. And it was indeed immediate. I was ordered to leave right away, accompanied by with my police shadow.

“You must leave France at once, but we can’t allow you to exit the city to the east. You’ll have to go west, via Spain. How does that suit you?”

It wasn’t really a matter of what suited me. I would just have to go wherever I must. But Spain was fine with me; it was a country I had always wanted to visit.

“I don’t mind,” I said, “but of course I’ll need permission from the Japanese authorities to travel there. What should I do?”

“Just wait over there; we’ll negotiate with the Japanese embassy for you,” was the response. And later I was led to the Police des Étrangers office, with which I was already quite familiar.

At the office, I saw around a hundred plainclothes detectives at their desks, sifting through similar looking documents that they were pulling out of or putting back into files. On each file a name was written, no doubt all considered dangerous individuals whom the police must keep a close eye on, and inside seemed to be a dozen or more sheets of paper.

The detectives, seated in the middle of the room, occasionally cast me a quick glance as they flipped through the pages of their files. Like their counterparts in Japan, not a single one had a look of humanity in his eyes. Their expressions reminded me of the thieves and swindlers I had seen in La Santé Prison – or even worse.

It was around noon. All of them were about to head off for their midday meal. I asked the man next to me about my own lunch, and he went to check with someone nearby who seemed to be in charge. I was told that they’d get me anything I wanted, so I listed up some extravagant items and also asked for a bottle of good white wine.

There were always four or five of the detectives on hand, and around two o’clock those who had gone out to lunch began to trickle back to the office.

The person sent to the Japanese embassy on my behalf had yet to return. I asked several times for permission to go to the deputy secretary’s office but it was not granted.

Tired of waiting and bored – and annoyed by all the looks I was getting from the detectives – I kept taking sips from my bottle of wine, even though I’m not much of a drinker.

Finally, around four in the afternoon, someone arrived from the deputy secretary’s office to escort me there. I met the deputy secretary and talked to him for a while until a tall Japanese man arrived who had a long and rather hazy visage. He was accompanied by the policeman who had been sent to fetch him from the embassy. I had heard the Japanese man’s name mentioned before: it was Sugimura Tarō, the first secretary at the Japanese embassy in Paris.

After exchanging greetings with the deputy secretary, Sugimura asked for permission to discuss something with me in private. The deputy secretary opened a door to a separate room for us to use.

“I just learned of your deportation order from the policeman sent to the embassy” Sugimura began. “I came here to do whatever I can to negotiate on your behalf.”

He then went into some detail of how he could mediate. The Japanese government had forbidden the embassy from issuing any passport to me. This meant I could not receive permission to travel to Spain. The embassy would ask for the deportation to be delayed several months and pledge to take responsibility for me in the meantime.

After our talk, Sugimura made this request to the deputy secretary using extremely polite language, but was told that a deportation order, once issued, cannot be rescinded. Hearing this, Sugimura said that he would have to return to the embassy to consult further with the other officials there.

I asked the deputy secretary whether the Spanish officials would allow me to cross the border from France if the embassy didn’t issue me a passport.”

“I don’t know. That’s up to them.”

“And what would I do if Spain won’t let me in?”

“All I can say is that if you are found in France, you’ll be put right back in prison.” His response reminded me of an interesting story my French teacher once had told me back in the days when I was enrolled at a language school. It was a tale of a thief who was about to be arrested near a border and tried to escape by crossing over into the neighboring country. Once he stepped over the border he stuck out his tongue like a child at the policeman giving chase, who stamped his fists on the ground in frustration.

With that story in mind, I jokingly said:

“So, in that case, I’ll either be thrown in a Spanish prison or one in France; or perhaps each side will grab one leg and leave me suspended for days in the middle?”

“I suppose that is the situation,” he replied quite earnestly.

I was sent back to the first room and waited a couple of hours there before being summoned again to the deputy secretary’s office, where I was told – perhaps because of Sugimura’s intervention – that I was to depart immediately for Marseille.

“You aren’t allowed to meet anyone. An officer will escort you to the station and you will have to board the first available train.”

We arrived at Gare du Lyon by automobile, not long before the departure of the eight o’clock express train.

I saw a police officer who was waiting until my train pulled out of the station and then seemed to turn around to leave. I had been told that my departure and arrival time had been wired to the Marseille police, so I thought it would cause the comrades in Lyon too much trouble if I stopped off there along the way. But I arrived in Marseille the next morning to find no police – uniformed or otherwise – waiting for me at the station.

I went to the Japanese consulate after I found a place to stay. There I met a newly appointed consul named Suga, who just a week before had been working under Sugimura at the embassy.

Suga went to the police station in Marseille, where he succeeded in insisting that the “first boat,” which I had been ordered to take, would be a Japanese vessel. He then went to the ticket office for the ship and negotiated so that I could purchase a berth without a passport. It was arranged for me to travel on the Hakone Maru, a Japanese vessel scheduled to depart in exactly one week.

While awaiting the departure, I telegraphed home and also sent telegraphs and letters to friends in Paris and Lyon. What set my mind at ease as I made my preparations was that none of my friends or comrades had experienced too much trouble on my account.[18]

Since Paris had issued me an “immediate deportation” notice, I expected to be closely watched in Marseille. Hoping to limit that intrusion as much as possible, I stayed at the nicest hotel in the city.

For the first few days I was on the lookout for police surveillance, but I could not detect anything; nor did the hotel treat me differently from other guests. I could stroll around freely outside without anyone tailing me. And when I returned to the hotel, no questions were asked about where I had gone.

The consulate apparently asked the police casually about me, but they did not send anyone to meet me at the train station when I arrived in Marseille. On my train there had been a robbery, which seemed to cause the police some problems, but I don’t think that can account for why no one was sent to the station to meet my train. I imagined that it would be necessary to present myself at police headquarters immediately upon arrival, but the consulate informed me that it wasn’t necessary since they had gone there to sort things out for me.

The situation called to mind the talk among the lady killers back at the Grand Salon; my deportation order, supposedly so strict, had turned out to be as lax as those for my fellow prisoners. It reminded me of a Hungarian comrade I’d seen at the Libertaire office. He was later deported, but just a few days after that I saw him strolling around the neighborhood. My lawyer, too, following my trial, gave me a casual, “See you later” as he departed.

If this was standard procedure, there was no reason to take the term “immediate” too literally and leave right away; or even if you did leave, you could always return again. In my inexperience I had thought that once the order had been issued, you must leave; and it was with that expectation fully in mind that I had taken the stage to give my speech on May Day.

I considered fleeing Marseille to travel around illegally, provided I could round up some money from Paris or somewhere else. I thought about bouncing around here and there, maybe heading back to Paris or traveling to Germany or Italy, or wherever else I wanted to go.

I spent a night engrossed in these plans, not that it would have been that difficult to arrange. I had pondered the idea before and come up with various schemes. All I needed was the money and I could be off.

Nearly resolved to attempt an escape, I made little excursions of a half or an entire day to see whether anyone was keeping an eye on me, and thereby confirmed that I was not under surveillance. I discussed the plan at the home of a comrade in Marseille, who told me that the necessary means were at hand.

Regretfully, I had to abandon my plan of escape when a letter mailed from Japan prior to my arrest arrived; it listed all the problems back home and asked why I hadn’t returned yet. It was enough to convince me that I had better behave myself and go home.

Two days before my departure the consulate sent me a second-class ticket to Yokohama along with a bill:

Bill due: 5,000 francs

Date

Ōsugi Sakae

Consul, Mr. Suga

On the following day some money from Japan also arrived. It was enough to purchase a third-class ticket, but I used it to hastily buy some gifts before my departure.

When it came time to board the ship, I first offered my farewells to the police, as recommended by the consulate. I went to the police station in the evening, carrying my hand luggage; a friend was to bring the rest of my baggage before the ship departed the next morning. After visiting the police station I intended to board the ship for a moment to confirm where I would be sleeping and then go back on land to attend a farewell party with friends.

The head of police had a long telegraph in front of him from Paris headquarters. After looking through various things, he assigned a detective to escort me to the ship.

On board, I took care of a few things and was ready to leave to meet my friends for dinner. But just as I was about to step off the ship, the detective ran up the gangplank with three others to block my way.

“Once you’ve boarded you can’t leave. You’ve already crossed the border. If you step off the ship you are reentering France and will be locked up for six months.”

It was absurd. I protested that he should have told me that before I boarded the ship, but to no avail. I had a crew member telephone my friends to let them know what had happened and then went into my cabin to sleep.

The ship lifted anchor early on the morning of June 3.

Tokyo - August 10, 1923

[1*] I wrote in “Escaping Japan” [first chapter of My Escapes from Japan] that my first encounter with the carte d’identité was in Paris, but that was only because I didn’t want readers to know at the time where I entered France and what were my reasons for going there.

[2*] Now it is safe for me to say that I arrived in Marseille on February 13, after having departing Shanghai on January 5 on the “André Lebon.”

[3*] I overheard this rumor a couple days before May Day but later learned that the Japanese government had, by that time, already ordered its embassy in Germany to search for me and sent the same directive to other embassies and consulates in Europe.

[4*] I later learned that around a dozen men and women at the hall in Saint Denis had tried to wrest back from the police the person they only knew as the “Japanese comrade.” Workers also clashed with the police in front of the station where I was held, and were showered with kicks and blows by the police. By the end of the fight, a hundred or so workers were said to have been arrested.Even from inside the station I could hear the sound of the struggle and of angry shouting.

[1] Ōsugi stayed at 37 chemin de l'Étoile d'Alaï, in the west of Lyon, according to French police records.

[2] Shō Keishū (Japanese reading of his name); on of the Chinese delegates chosen to attend the planned anarchist congress in Berlin.

[3] The CGTU (Confédération général du travail unitaire) was a Communist-led labor union formed in 1922 ou of a split with CGT (Confédération général du trvail).

[4] Hayashi Shizue (1895-1945); a painter and friend of Osugi's from anarcho-syndicalist circles in Tokyo. Resided in France and Germany from 1921 to 1926.

[5] André Colomer (1886-1931); editor in the early 1920s of the anarchist newspaper le Libertaire and the journal la Revue anarchiste. Joined the French Communist Party in 1927 and died in Moscow.

[6] Paris taxi drivers were on strike that day.

[7] The meeting apparently was held at a domed, two-story building on rue Légion d'honneur, facing the Basilica Cathedral.

[8] As in the original text, "x" marks the spot of the censored words or passages, each indicating a deleted Japanese character.

[9] Interspersed in the redacted text are the words tobu (fly out) and hikaru (shine), but the intended meaning is unclear.

[10] According to a May 2 article in le Figaro, a crowd of five to six hundred, led by two city councilmen, marched on the police station in Saint Denis to free Ōsugi, and in the clash that followed five policement were seriously injured.

[11] Osugi's assumed name is listed as "Tung Chen Tang" in French police records.

[12] Roughly twelve by twelve feet.

[13] The 1922 silent film Crainquebille, directed by Jaqued Feyder.

[14]Muraki Genjirō (1890-1925); an anarchist arrested in 1924 for his failed attempt to avenge Osugi's murder by assasinating Fukuda Masatarō, the general in charge of martial law after the Great Kanto Earthquake. Died of illness during the preliminary investigation of his case.

[15]Published as a chapter in the book Nippon dasshutsu ki (My Escapes From Japan), titled "Toilets of Paris" (Pari no benjo).

[16]Henry Torrès (1891-1966); a lawyer, writer, and politician. Was a member of the French Communist Party in the early 1920s, but defended a number of anarchists in court, including Germaine Berton and Ernesto Bonomini (1903-1986).

[17]"E" is short for "Ei," the Chinese reading of the kanji character for "Sakae."

[18]Osugi never learned that his Chinese comrade, Shō Keishū, was deprted from France for his connection to him.