August 16, 1949

Dear J:

I think it is time I wrote down some of the ideas and problems that I have been thinking about during the last few weeks, even though there are still some areas in which I see the light very dimly.

The first point which throws light on the Logic, Lenin and contemporary politics is: We can assert categorically that Hegel had two main enemies - the two forms of idealism.* These are:

I. Subjective idealism - the 2nd attitude of thought to objectivity, and;II. Intuitional idealism - the third attitude of thought to objectivity

The first is the school of the right idealists or reformists. The second is the school of the left idealists, abstract revolutionists or "positivists". It should be noted here that in the decade after the turn of the century the factional fight between these two schools and Hegel raged. There are innumberable books, letters, etc. to document this. Hegel, as we know, represented what we can call the principle of permanent revolution, or self-movement by continually developing negativity. We can elaborate this further by calling it a conception of development which is always at its goal and which is nevertheless in constant self-movement by negativity. It is therefore in opposition to:

reformism - for whom the goal is always in the future, and;

abstract revolutionism - for whom, once the goal has been reached, there is no more negative development or mediation, and all that is required is an organization of what has been accomplished.

As we know the movement of the Logic in general is from the:

Universal - immediate unity of opposites, the indeterminateto the Particular - mediation of opposites, first negation, determinationto the Individual - Unity of opposites or negation of negation in which the subject is an immediate which has overcome mediation.

In order that this general movement should immediately have a less esoteric meaning, we can roughly characterise these three stages as:

Universal - immediate unity of opposite or given situation which is the result of previous revolutionParticular - critical period of opposition of forces, or mediation and negation in preparation for a revolutionIndividual - the revolution itself

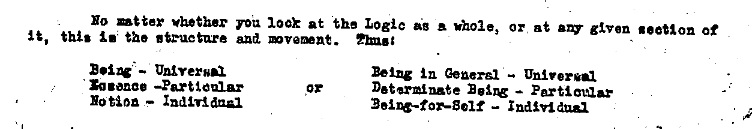

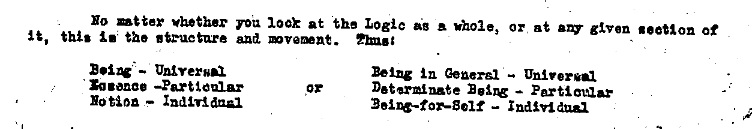

No matter whether you look at the Logic as a whole, or at any given section of it, this is the structure and movement. Thus:

Being - UniversalEssence - ParticularNotion - Individualor

Being in General - UniversalDeterminate Being - ParticularBeing-for-itself - Individual1

For the first section of the Logic, Wallace probably describes the process as clearly and simply as anybody can:

U "If Being... is truly apprehended as a process as a becoming, then this tendential nature, or function, or vocation implies a result, a certain definiteness which we missed before.

P "Somewhat has become: or the indeterminate being has been invested with definiteness and distinct character. The second term in the process of thought therefore is reached. Being has become Somewhat; and is real, because it implies negation... is necessary to be somewhat - to limit and define. This is the necessity of finitude: in order to be anything more and higher, there must come, first of all, a determinate being and reality. But reality, as we have seen, implies negation: it implies limiting, distinction and opposition. Everything finite, every 'somewhat' has somewhat else to counteract, narrow and thwart it. To be somewhat is an object of ambition, as Juvenal2 implies: but it is only an unsatisfactory goal after all. For somewhat always implies something else, to which it is in bondage. The two limit each other; or the one is the limit of the other... Such is the character of determinate being. It leads to an endless series from some to other, and so on ad infinitum; everything as a somewhat, as a determinate being, or as in reality, is for something else, and that again from some third being, and so the chain is extended... and so the same story is repeated in endless progression, till one gets wearied with the repetition of finitude, which is held out as infinite.

I "Thus in determinate being as in mere being we see the apparent point issuing in a double movement - alteration from some-being to somewhat else and vice versa. But a movement like this implies after all that there is a something which alters into somewhat and thus retains itself, is a being which has risen above alteration, which is independent of it; which is for itself and not for somewhat else... The new result is something in something else; the limit is taken up within; and this being which results is its own limit. It is Being-for-self the third step in the process of thought under the general category of Being. The range of Being which began in a vague nebula, and passed into a series of points, is now reduced to a single point, self complete and whole. This Being-for-self is a true infinite which results by absorption of the finite".3

From this general conception of the movement of the Logic from U to P to I, certain broad generalisations can be drawn:

1) The ultimate, the goal to which the whole logical development moves is the revolution, the individual, and these are Hegel's chief concerns. Individuality, revolution, self-determination, self-activity can all be regarded as more or less equivalent terms so long as we realize that there are stages of revolution, individuality, self-determination and self-activity. (For this reason the less controversial term personality might be substituted for individuality).

2) Individuality and revolution is the result of the overcoming of particularity. It is a self-relation arrived at by negation of negation. This process of U-P-I cannot be over-emphasized. The diametrically opposed conception of idealist philosophers - which lurks in ambush for everybody who doesn't have this process clear - is that the individual is a mode, a limitation, a negation, a determination (i.e. the first negation) of the universal and therefore finite. This is the philosophic root of all totalitarianism. See SL #193 and LL II, p. 167.4

3) Since precisely this achievement of self-relation is the revolution, all stages of the succeeding revolutions must and can be looked for precisely at those nodal points in the Logic where individuality overcomes particularity.

"All revolutions, in the sciences, no less than in general history, originate only in this, that the spirit of man, for the understanding and comprehension of himself, for the possessing of himself, has now altered his categories, uniting himself in a truer, deeper, more inner and intimate relation with himself" (Hegel).5

So much for the movement of the Logic in general. There is also, however, what we may call the polemical movement of the Logic, i.e. in terms of the conception that Hegel was fighting the Ring-wing Reformists and the Left-wing positivists. Like all historically oriented polemics, this conception of the Logic enables us to penetrate more deeply into it.

Prior to every leap into subjective freedom, Hegel deals with the Reformists in one form or another, i.e. with those who are caught in particularity or determinate Being and seek to get out of this particularity by counterposing to it the abstract universal. These people are caught in the "ought" or bad infinite. (See the long excerpt in the Nev. document, pp. 94-996 from which I quote only one passage here: "The infinite - in the ordinary sense of bad infinity - and the progress to infinity, are, like Ought, the expression of a contradiction, which pretends to be the solution and the ultimate. This infinite represents the first exaltation of sensuous imagination, above the finite into Thought, the content of which, however, is Nothing, or that which is expressly posited as not-being: it is a flight from barrier which, however, neither collects itself nor knows how to lead back the negative to the positive. This imperfect reflection has completely before it the two determinations of the true infinite - the opposition of finite and infinite and the unity of these; but it fails to reconcile these two thoughts: either inevitably evokes the other, but in this reflection they merely alternate" (LL, I, 164). (Note, LL, II, 67, where Hegel says "infinity... is contradiction as it appears in the sphere of Being").

After the leap into subjective freedom, Hegel mentions the reformists only in passing, e.g. p. 176 LL. After the leap, what he is concerned with are those idealists who take up an attitude of abstract understanding to the achieved individuality or negation of the negation. Thus, e.g. Larger Logic, I, p. 175, the polemic against Leibniz7).

By Leibniz's attitude of abstract understanding to the achieved individuality (prototype of all such attitudes to the revolution) or what Hegel calls Leibniz's conception of "the absoluteness of abstract individuality", the following is meant:

The category of Being-for-Self (which is the first emergence of individuality or self-determination) means that the Other has been reflected into the self, i.e., that the self is no longer limited by others but has other as its own content (LL. I, p. 171). The self is therefore independent. Such independent selves Leibniz called monads.

Immediately, however, Leibniz was confronted with explaining how these independent monads were related to one another. Instead of seeing these selves as negatively developing ones which would represent a new particularity and therefore the need of another synthesis and leap into freedom (the development of the Logic through Quantity to Measure and Essence), Leibniz stopped with these independent monads and sought to relate them through God as the Monad of Monads or the principle of organization (called by Leibniz the pre-established harmony). The result is the independence of the monads, or the revolutionary achievement becomes subordinated to their harmonious relation in the Monad of Monads, or the counter-revolutionary organization. As Hegel explains in the History of Philosophy,8 there are in Leibniz two views of the monads - one as spontaneously generating its representations, and the other, as a moment of necessity. And the latter wins out: "Before God the monads are not to be independent, but ideal and absorbed in him". Thus we have a perfect example of what Lenin in 1915 called philosophical idealism - "a one-sided exaggerated extreme development (inflations, distention) of one of the features, sides, facets of knowledge, into an absolute, divorced from matter, from nature, apotheosized".9

It should be emphasized here that Leibniz is not "responsible" for the transformation of Being-for-Self (the Individual) into Many Ones and therefore the dialectic of quantity (P). Quite the reverse. Leibniz's theoretical and therefore political crime is precisely the refusal to recognize the inevitable negative development, i.e. transformation into particularity and therefore negation of negation at a higher stage. Because he stops at Being-for-Self, or the independence of the individual as the final revolution, he will need an external third party to perfect the revolution. On the other hand, from the organic movement, the transformation of quality into quantity will emerge Measure, a new synthesis, and from that Essence, which is the leap from this synthesis. Note that Measure is Essence in the realm of Being. Thus from the above we have:

Quality - UQuantity - PMeasure - I (but still in the realm of Being)

Using this analysis of the Logic of the realm of Being as a springboard, I believe that we can show an analogous pattern of development in the other realm of the Logic.

As for the distinction between the different major sections of the Logic, I have been thinking that in addition to seeing the Realm of Being as the method of thought of the market (i..e commodities, transformation of use-values in exchange values, etc) and the realm of Essence as production, it is necessary to analysze the major stages more fundamnentally in terms of the development of human freedom. (See LL, I, 350, and SL #98 where Hegel indicates the variety of realms in which the method applies). Thus it seems to me that in the Realm of Being we can see the development from abstract individuality (Being-for-Self) through the particularity of political equality (Quantity or indifference to quality) to the synthesis of political democracy (Measure). And in the Realm of Essence we can see the development from labor as the principle (Ground, classical political economy, law of sufficient reason) to the mediation of economism (substance and necessity). I have in mind here the way in which: 1) Marx links Liberty, Equality and Bentham with the market,10 and; 2) the basic11 conception which he had of the ever-deepening (increasing concrete universality) development of human freedom - from Christianity to political democracy - to which we can at least add, since the emergence of the 2nd International - the concept of economic or industrial democracy - and perhaps other stages of freedom.

In this connection what Wallace says in the Prolegomena12 on "Being for self" representing "the sentiment of universal war - the bellum omnius contra onmes", the polemical attitude toward others as the very basis for Being-for-Self, is a key.

My best to Constance and Nob. Hope to see you soon.

As ever,

G-

* A footnote is necessary here on Hegel's attitude to Empiricism or the first attitude of thought to objectivity. Hegel doesn't conceive the empiricists as serious enemies. He recognises that empiricism once had a contribution to make (SL #38) in making man feel at home in the world, but throughout his work he only slashes in passing at any who would remain with the immediacy of sense-perception, mistaking it for truth. The fact of the matter is that after the French Revolution (i.e. in philosophy after Kant) non-critical attitudes to society play no important role in social development.

1 The editor has reformatted the text at this point. The original looks like this:

2 Juvenal (Latin: Decimus Junius Juvenalis), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century AD. He was the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the Satires.

3 The quoted passages are from William Wallace, Prolegomena to the study of Hegel's philosophy and especially of his logic on Hegel. There is a copy of the second (1894) edition of Wallace's text on the Internet Archive. Grace Lee (Boggs) appears to have been working from the earlier, 1874, edition, because some of the text she quotes is different to the text in the 1894 edition. In the 1984 edition the quotes passages are in pages 423-6.

4 'SL' is an abbreviation of 'Shorter Logic', a colloquial name for Hegel's Part One of The Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences), (1830). #193 is the subsection 'Transition to Object', in the section on The Notion. 'LL' is an abbreviation of 'Larger Logic', a colloquial name for Hegel's Science of Logic, (1812-16).

5 The quote is from Hegel's Philosophy of Nature (1817), which is Part Two of The Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences. The quoted section does not appear to be on the version of the Philosophy of Nature on the MIA.

6 'The Nevada Document', was written by CLR James in late 1948. It was published, years later, with a new introduction by James, as Notes on Dialectics: Hegel, Marx, Lenin (1980), by Allison and Busby in London and Lawrence Hill in the USA.

7 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) was a German polymath and philosopher.

8 Hegel's Lectures on the History of Philosophy, (1805-06). The quote is from near the end of the section on Leibniz.

9 This appears to be a quote from Lenin's Philosophical Notebooks on Hegel.

10 'Liberty, equality and Bentham' is a reference to the end of Chapter Six of Volume One of Marx's Capital.

11 This word is unclear on the manuscript - 'basic' is the editor's best guess at the word Grace Lee (Boggs) used.

12 William Wallace, Prolegomena to the study of Hegel's philosophy and especially of his logic on Hegel.