William Z. Foster

The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons

THE RELIEF ORGANIZATION—RATIONS—SYSTEM OF DISTRIBUTION —COST OF COMMISSARIAT—STEEL STRIKE RELIEF FUND —COST OF THE STRIKE TO THE WORKERS, THE EMPLOYERS, THE PUBLIC, THE LABOR MOVEMENT

In all strikes the problem of keeping the wolf from the door is a pressing one. Usually it is met by the unions involved paying regular benefits of from $5.00 to $15.00 per week to each striker. But in the steel strike this was out of the question.(1) The tremendous number of men on strike and the scanty funds available utterly forbade it. To have paid such benefits would have required the impossible sum of at least $2,000,000 per week. Therefore, the best that could be done was to assist those families on the brink of destitution by furnishing them free that most basic of human necessities, food. Ordinarily in strikes the main body of men are able to take care of themselves over an extended period. The danger point is in the poverty-stricken minority. From them come the hunger-driven scabs who so demoralize and discourage the men still out. Hence, to take care of this weaker element was scientifically to strengthen the steel strike, and to make the best use of the resources available.

The great mass of strikers and their incomplete organization making it manifestly impossible for each union to segregate and take care of its own members, the internationals affiliated with the National Committee (with the two exceptions noted) pooled their strike funds and formed a joint commissariat.(2) They then proceeded to extend relief to all needy strikers, regardless of their trades or callings, or even membership or non-membership in the unions. To get relief all that was necessary was to be a steel striker and in want. This splendid solidarity and rapid modification of trade-union tactics and institutions to meet an emergency is probably without a parallel in American labor annals.

The commissariat was entirely under the supervision and direction of the National Committee. Its national headquarters was in Pittsburgh, with a sub-district in Chicago. Goods were shipped from these two points. In Pittsburgh they were bought and handled through the Tri-State Co-operative Association, with National Committee employees making up the shipments. In Chicago the same was done through the National Co-operative Association. As Bethlehem, Birmingham, Pueblo and a few other strike-bound towns lay beyond convenient shipping distance from the two distributing points, the men in charge there were sent checks and they bought their supplies locally.

The General Director of the commissariat was Robert McKechan, business manager of the Central States Wholesale Co-operative Association. He was paid by the Illinois Miners, District No. 2. He was ably assisted by A. V. Craig (Ass’t. Director), Enoch Martin (Auditor—also paid by Illinois miners), Wm. Orr (Warehouse Manager), and E. G. Craig. Secretary De Young was in charge of the Chicago sub-district. The local distributing centres were operated altogether by National Committee local secretaries and volunteer strike committees, with an occasional paid assistant.

All told, 45 local commissaries were set up throughout the strike zone. This elaborate organization was created and put in motion almost over night. Within a week after Mr. McKechan arrived in Pittsburgh, he and officials of the National Committee had devised the commissary system—with hardly a precedent to go by,—organized its nation-wide machinery, and started the first shipment en route to the many strike centres. To break in this machinery, a small pro rata of provisions, based upon the number of men on strike, was sent to each place. The following week this was doubled, and each succeeding week it was increased to keep pace with the growing need. It finally developed into a huge affair. Few strikers had to be turned away for lack of food, and these only for a short while until the necessary additional stuff could be secured from the shipping points. Throughout the fourteen weeks it was in operation the commissariat, despite the tremendous difficulties it had to contend with, worked with remarkable smoothness. It was one of the greatest achievements of the entire steel campaign.

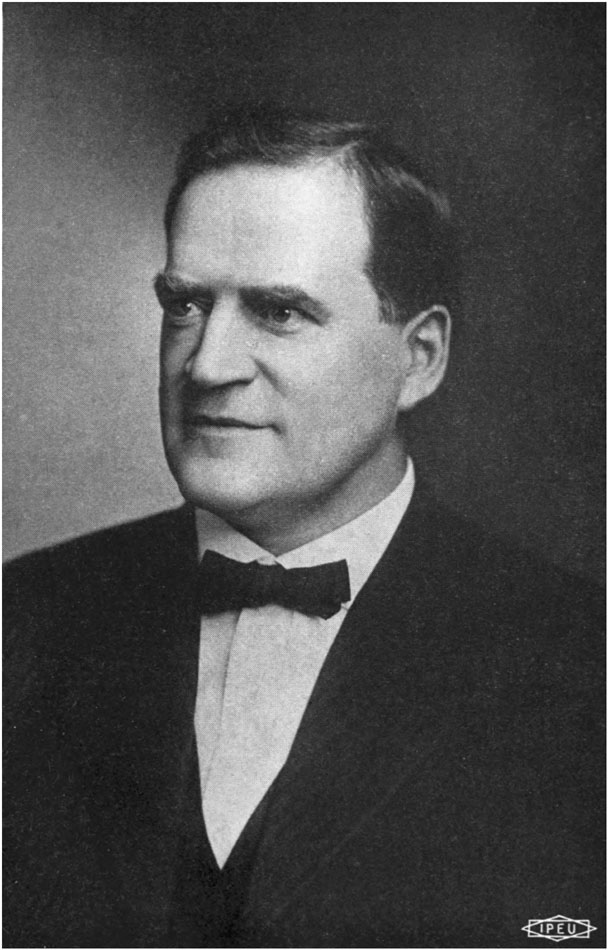

JOHN FITZPATRICK

Chairman, National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers.

The wide extent of the relief work made it necessary to develop the most rigid simplicity and standardization in the apportionment of food to the strikers. Hence, only two sizes of rations could be used; one for families of five or less, and the other for families of six or more. These were varied from time to time, always bearing in mind the cooking facilities of the strikers and the many food likes and dislikes of the various nationalities. To facilitate the carrying away of the food and to make it last the better, two commissary days were held each week, in each locality. The rations were listed on large posters (white for families of five or less, and green for families of six or more) which were prominently displayed in the local commissaries in order that the strikers could see exactly how much provisions they were entitled to. The following are typical rations:

| FAMILIES OF FIVE OR LESS | |||

| First Half Week | Second Half Week | ||

| Potatoes | 15 lbs. | Bread | 4 loaves |

| Bread | 4 loaves | Tomatoes | 1 can |

| Tomatoes | 1 can | Corn | 1 " |

| Peas | 1 " | Peas | 1 " |

| Navy beans | 4 lbs. | Red beans | 4 lbs. |

| Oatmeal | 1 box | Kraut | 2 cans |

| Bacon | 1 lb. | Dry salt meat | 1 lb. |

| Coffee | 1 " | Syrup | 1 can |

| Milk | 1 can | ||

| FAMILIES OF SIX OR MORE | |||

| First Half Week | Second Half Week | ||

| Potatoes | 10 lbs. | Potatoes | 10 lbs. |

| Bread | 5 loaves | Bread | 5 loaves |

| Tomatoes | 1 can | Tomatoes | 1 can |

| Corn | 1 " | Corn | 1 " |

| Peas | 1 " | Peas | 1 " |

| Navy beans | 5 lbs. | Kraut | 2 cans |

| Oatmeal | 2 boxes | Red beans | 5 lbs. |

| Bacon | 1 lb. | Dry salt meat | 1 lb. |

| Coffee | 1 " | Milk | 1 can |

| Milk | 1 can | Syrup | 1 " |

It was not contended that these rations were enough to sustain completely the recipients’ families; but they helped mightily. Few, if any, went hungry. Single men in need received a half week’s rations to last the week. The greatest care was taken to have the supplies of the best quality and in good condition. Whatever the unions gave they wanted the strikers to understand was in the best spirit of brotherly solidarity.(3)

The provisions were distributed strictly according to the following card system:

1. Identification card: An applicant requesting relief would be referred to a credentialed volunteer relief committee. If this committee deemed the case a needy one, it would issue the striker an identification card. This he was required to show when dealing at the commissary.

2. Record card: In addition, the relief committee would write out the data of the case upon a record card and turn it over to the local secretary in charge of the commissary, who would keep it on file.

3. Commissary card: When the applicant presented his identification card at the commissary, the local secretary, referring to the record card on file, would make him out a commissary card, white or green, accordingly as his family was of five or less, or six or more members. This commissary card entitled him to draw supplies.

The commissary card had a stub attached. When a striker got his first half week’s supplies, this stub would be detached and retained by the commissary clerk. Upon his next visit the body of the card would be taken up. Two important purposes were served by this collection of the commissary cards—rather than having permanent cards and merely punching them. First, the canceled cards being sent to the commissariat national headquarters, it proved conclusively that the strikers had actually received the provisions shipped to the district; and second, by compelling the strikers to get new commissary cards each week, it enabled the local secretaries to keep in close touch with those on the relief roll.

To lighten the load upon the many inexperienced men working in the various commissaries, a special effort was made to do as much of the technical work as possible in the main offices of the National Committee. Otherwise the commissariat could not possibly have succeeded. This consideration was a prime factor in restricting the buying of provisions to Pittsburgh, Chicago and the fewest practical number of outlying points. It also caused the adoption of the package system, all bulk goods, except potatoes, being prepared for delivery before leaving the warehouses. Likewise, the local bookkeeping was simplified to the last degree. In fact, for the most part the secretaries in charge of the commissaries hardly needed books at all. The whole system checked itself from the central points.

As an example of its working, let us suppose that the allotment of a certain town was 1000 rations. Accordingly, there would be shipped to that place exactly enough of each article to precisely cover the allotted number of rations. Then, if the secretary simply saw to it that he got what he was charged with and issued his supplies carefully in the right proportions, the whole transaction would balance to a pound, with hardly a scratch of a pen from him. The bookkeeping was all done at the general offices. The latter’s assurances that each striker had received his proper ration and that the right number of rations had been issued were, in the first place, the ration posters hanging on the walls of the commissary; and in the second, the returned canceled commissary cards. Barring an occasional slight disruption from delayed shipments, spoiled goods, shortages, and a little carelessness here and there, the system worked very well.

The commissariat was in operation from October 26 until January 31, three weeks after the strike had ended. It was continued through this extra period in order to help to their feet the destitute strikers who had fought so nobly. Probably nothing done by the unions in the entire campaign won them so much good will with the steel workers as this one act.

The total cost of operating the commissariat was $348,509.42. The significance of this figure stands out when it is reduced to a per man basis. At the strike’s start there were 365,600 men out, and at its finish about 100,000. Considering that few serious breaks occurred until the eighth to tenth weeks, a fair average for the whole period would be about 250,000. Accordingly, this would give (disregarding the three weeks after January 8) a total relief cost of a fraction less than $1.40 per man for the entire fifteen weeks of the strike, or about one day’s strike benefits of an ordinary union. Reduced to a weekly basis, it amounts to but 9-1/3 cents for each striker. Just how unusually small this sum is may be judged from the fact that the International Molders’ Union paid the few men it had on strike regular benefits of $9.00 per week after the first week. The fact is that, except for a small, impoverished minority, the steel workers made their long, hard fight virtually upon their own resources.(4)

To help finance the commissariat the American Federation of Labor was requested to issue a general appeal for funds, which it did. Then, to add force to this call, the National Committee recruited and put in the field a corps of solicitors, including among others, Anton Johannson, J. D. Cannon, J. W. Brown, J. G. Sause, Jennie Matyas and G. A. Gerber. At a meeting in Madison Square Garden on November 8 a collection of $150,000 was taken up. Many local unions, notably those of Altoona, Pa., gave half their local treasuries and assessed their members one day’s pay each. The Marine Engineers, local 33 of New York, contributed $10,000; the International Fur Workers’ Union $20,000; the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union, $60,000; and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, $100,000. All these donations were highly praiseworthy, but especially the last one mentioned, because the organization making it is not affiliated to, nor even in good grace with, the A. F. of L.

The total amount collected and turned over to the National Committee was $418,141.14. This more than covered the entire cost of the commissariat, leaving $69,631.42 to be applied to other expenses. Thus, taking them as a whole, the co-operating international unions in the National Committee were not required to pay a penny to the feeding of the strikers and their families. The commissariat was a monument to the solidarity of Labor generally with the embattled steel workers.

Naturally, the employers bitterly hated the commissaries. They sneered at the quantity and quality of the food given out by them, and in many places printed handbills in several languages advising the strikers to go at once to union headquarters and demand strike benefits in cash. And by the same token, the strikers held the commissaries in high esteem. The foreign-born among them especially, would stand around watching with never-ceasing wonder and enthusiasm the stream of men and women coming forth laden with supplies. To them there was something sacred about the food. Many of them in desperate circumstances had to be practically compelled to accept it; not because they felt themselves objects of charity, but because they thought others needed help worse than they. They conceived the whole thing as a living demonstration of the solidarity of labor. The giving of the food produced an effect upon their morale far better than could have come from the distribution of ten times its value in money. The commissariat enormously strengthened the strikers. Without it the strike would have collapsed many weeks before it did. Unions in future great walkouts will do well to study the steel strike commissary plan.

Strikes, even the smallest, affect so many people in so many ways that it is difficult under the best of circumstances to compile accurate data upon their cost. In the case of the steel strike it is next to impossible to do so. The great number of steel companies and the armies of men involved; the wide scope of the strike; the condition of outlawry in many steel districts; the fact that the strike was lost; the workers’ numerous nationalities and imperfection of organization—all these and various other factors make it exceedingly difficult, at least at this early date, to give more than a hint of the strike’s cost.

In the steel strike, as in all others, the burden of suffering fell to the workers’ lot. To win their cause they gave freely of their lives, liberty, blood and treasure. A poll of the National Committee local secretaries yields the following list of strike dead:

| Total | 20 |

| Buffalo | 2 |

| Chicago | 1 |

| Cleveland | 1 |

| Farrell | 4 |

| Hammond | 4 |

| Newcastle | 2 |

| Pittsburgh | 1 |

| West Natrona | 2 |

| Wheeling | 1 |

| Youngstown | 2 |

The killed were all on the strikers’ side, except two. The above list properly includes Mrs. Fannie Sellins. But it does not include the scores of scabs who, because of their own or other incompetent workers’ ineptness, were roasted, crushed to death, or torn to pieces in the dangerous steel-making processes during the strike. Although the steel companies were exceedingly alert in suppressing the names of these ignoble victims to their greed, it is a well-known fact that there were many of them. There was hardly a big mill anywhere that did not have several to its account.

How many hundreds of strikers were seriously injured by being clubbed and shot will never be known, because most of them, especially in Pennsylvania, healed themselves as best they might. With good grounds they feared that disclosing their injuries to doctors would lead to their arrest upon charges of rioting. The number of arrested strikers ran into the thousands. But so orderly were the strikers that few serious charges could be brought against them. They were jailed in droves and fined heavily mostly for minor “offenses.” Except in Butler, Pa., where a score of strikers were arrested for stopping a car of scabs on the way to work (framed-up by the State Police) and sent to the penitentiary, no strikers anywhere in the whole strike zone received heavy jail sentences. Considering the terrific provocations offered the men and the extreme eagerness with which the courts punished them, this remarkable record is an eloquent testimonial to their orderliness.(5) Of course, the companies did not neglect to avail themselves of the heartless blacklist. Just now hundreds of their former employees, denied work and forced to break up their homes and leave town, are criss-crossing the country looking for opportunities to make new starts in life.

As for the cost to the strikers in wages, the Philadelphia Public Ledger of January 10, two days after the strike was called off, carried a special telegram from Pittsburgh, stating (authority not quoted) that the wage loss in that district was $48,005,060.35, specified as follows:

| Clarksburg, W. Va. | $310,000.00 |

| Wheeling District | 6,100,000.00 |

| Donora | 1,200,000.00 |

| Steubenville district | 2,260,000.00 |

| Youngstown | 15,500,000.00 |

| Monessen | 2,660,000.00 |

| Brackenridge | 450,000.00 |

| New Kensington | 375,000.00 |

| McKeesport | 597,869.00 |

| Port Vue | 900,000.00 |

| Sharon-Farrell | 1,250,000.00 |

| New Castle | 705,000.00 |

| Homestead | 737,840.00 |

| Duquesne | 55,030.00 |

| Johnstown | 5,712,321.35 |

| Ellwood City | 35,000.00 |

| Butler | 1,450,000.00 |

| Aliquippa | 10,000.00 |

| Pittsburgh | 5,715,000.00 |

| Sharpsburg, Ætna | 435,000.00 |

| Vandergrift | 357,000.00 |

| Clairton | 165,000.00 |

| Rankin | 375,000.00 |

| Braddock | 650,000.00 |

To the above, the New York Herald of January 12 editorially adds an estimate of $39,000,000 for steel districts other than Pittsburgh, making a grand total of $87,000,000 as the strikers’ wage loss. But these figures, bearing the earmarks of Steel Trust origin, are too low. On the basis of the minimum figures of an average of 250,000 strikers for 90 working days (actual strike length 108 days) at $5.00 per day per man, we arrive at a total of $112,500,000.00, or $450.00 per average striker. Doubtless these figures are also too low, but they will serve to indicate the tremendous sums of money the already poverty-stricken steel workers were willing to sacrifice in order to change the conditions which Mr. Gary so glowingly paints as ideal.

The loss to the steel companies must have been enormous. Without doubt it runs into several hundred millions of dollars. The items going to make up this huge bill are many and at this time impossible of accurate estimate. There must have been not only a complete cessation of profits during the strike period, but also a vast outlay of money to finance the strike-breaking measures, such as maintaining scores of thousands of gunmen to guard the plants; paying rich graft to employment offices and detective agencies for recruiting armies of scabs, who, receiving high strike wages, idled for weeks around the plants, shooting craps, playing cards, pitching quoits, and absolutely refusing to work; keeping on the payroll great staffs of office workers with nothing to do, and high paid skilled workers doing the work of common laborers; corrupting police and court officials to give the strikers the worst of it, etc., etc. Besides, there should be added the cost of repairing the great injuries done the furnaces by their sudden shutting down, this item alone amounting to many millions of dollars. But a more important factor than all, perhaps, in counting the cost of the strike to the companies was the serious injury done to their wonderful producing organization by the permanent loss of thousands of competent men who have quitted the industry; the dislocation of many thousands more from jobs for which they were well fitted and the substitution in their places of green men; the lowering of the men’s morale generally, due to disappointment and bitterness at the loss of the strike, etc. We may depend upon it that the companies, following out their policy of minimizing the strike’s effects, will so juggle their financial and tonnage statements as to make it impossible for years to figure out what it really cost them, if it can ever be done.

The cost to the people at large is indicated by the New York Sun, quoted by the Literary Digest, January 31, 1920, as follows:

There was the loss to the railroads not only in freights from the steel plants, but in freights from general mills and factories which, failing to get their steel supplies, could not maintain their production and fulfill their own deliveries. There was the loss in wages in such mills and factories due to that failure to get their material on which their wage-earners could work. There was the loss in such communities to trade folk whose customers thus had their spending power reduced by the steel strike.—Hence this loss of steel tonnage begins at once to widen until the loss eventually could be figured in the billions.

For the privilege of having an autocracy in the steel industry the American people pay not only huge costs in unearned dividends each year, but also, occasionally, such monster special charges as the above. Garyism is an expensive luxury.

The foregoing figures and statements merely serve to point out the immensity of the steel strike by indicating its approximate cost to the strikers, the steel companies, and the public. Admittedly they are but loose estimates, based upon scanty data. Absolute accuracy is not claimed for them. The expenditures of the labor movement in the campaign can be more closely calculated, although they, too, are far from definite. They fall into three general classes: (1) those by the general office of the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers; (2) those by the A. F. of L. and co-operating international steel trades unions not through the office of the National Committee; (3) those by local steel workers’ councils and unions from their own treasuries. Of these the latter may be eliminated as impossible of estimation, there being so many local organizations involved and the after-strike conditions so unfavorable to statistics gathering. They were a minor element of expense compared to the other two, which we will try to approximate as closely as may be.

1. From the beginning of the steel campaign, August 1, 1918, until January 31, 1920, the total net disbursements of the National Committee for all purposes, after making deductions for refunds, transfers, etc., amounted to $525,702.72. This stretch of time may be divided into two parts: (a), Organizing period, from August 1, 1918, until September 22, 1919—during which time virtually all the 250,000 men enrolled in the campaign (see end of Chapter VII) had joined the unions; (b), Strike period, from September 22, 1919, until January 31, 1920—during which time the heavy special strike expenses were incurred. This period is extended three weeks past the date of the strike’s close, because the commissariat was still in operation and other important strike expenses were going on.

The total net disbursements made by the National Committee during the organizing period were $73,139.66, which amounts to a small fraction over 29 cents for each of the 250,000 men organized. The total net disbursements of the National Committee during the strike period were $452,563.06, or $1.81 for each of the 250,000 average strikers. Adding these two figures together gives $2.10 as the cost to the National Committee of organizing each steel worker and taking care of him during the whole strike.

2. The disbursements of the National Committee covered general organizing and strike expenses, such as commissary, legal, rent, printing, salaries, etc. The A. F. of L. and the co-operating international unions also incurred heavy expenses upon their own account, whose chief items were for keeping organizers in the field, paying strike benefits, and making lump donations to strike-bound local unions. At this date these expenditures may be only approximated.

For the above bodies almost the sole expense during the organizing period was for maintaining organizers. Forty would be a fair average of the number of these men actually kept at the steel industry work. In the earlier part of the campaign the number was far less; in the later part, considerably more. The cost of maintaining them per month may be set at not more than $400.00 each, for salaries and general expenses. Thus, for the 13-3/4 months of the organizing period the expense to the A. F. of L. and co-operating unions for this item would be about $220,000, or 88 cents per man organized. This is a top figure.

During the strike period, on an average, 75 organizers were kept in the field by these bodies. Due to increases in wages, etc., their upkeep should be calculated at about $500.00 per month each. For 4-1/4 months, September 22 to January 31, our strike period, this would amount to $159,375. To this should be added $100,000, which according to reports received approximates what the organizations paid in strike benefits and donations direct to their strikers and not through the office of the National Committee. This would make their total expenditures for the strike period $259,375, or slightly less than $1.04 per striker. Adding together the amounts for the organizing period and the strike period, we arrive at a grand total of $479,375, or $1.92 per man, spent during the entire campaign by the A. F. of L. and co-operating internationals.

The figures for the A. F. of L. and co-operating internationals are estimates,—the constant shifting of organizers during the campaign, their widely varying rates of pay, etc., making accuracy impossible. But from my knowledge of what went on I will venture that the figures cited are close enough to the reality to give a fair conception of this class of expenditures.

Combining the National Committee expenditures with those of the A. F. of L. and co-operating unions, we arrive at the following totals:

| Organizing Period: | |||||

| Expenditures | Per Man | ||||

| By Nat. Com. | $73,139.66 | $.29 | |||

| By A. F. L. & Unions | 220,000.00 | .88 | |||

| Total cost of orgnizing work | $293,139.66 | $1.17 | |||

| Strike Period: | |||||

| By Nat. Com. | $452,563.06 | $1.81 | |||

| By A. F. L. & Unions | 259,375.00 | 1.04 | |||

| Total cost of strike | $711,938.06 | $2.85 | |||

| Whole Campaign: | |||||

| Total cost to Nat. Com., A. F. L. & Unions | $1,005,007.72 | $4.02 | |||

In order to approximate more closely the actual cost of the campaign to the A. F. of L. and the twenty-four co-operating internationals forming the National Committee, the total of $479,375, figured in a previous paragraph as their independent expenditures, must be increased by $101,047.52, the amount they contributed directly to the National Committee for organizing and for strike expenses during the course of the campaign;(6) making a grand total outlay for them of $580,422.52. This in turn should be reduced by $118,451.23, the amount in the National Committee treasury on January 31, 1920. Against the remaining $461,971.29 must be checked off what the steel workers paid into these organizations in initiation fees and dues.

Inasmuch as the co-operating internationals received directly $1.00 to $2.00 (mostly the latter) from the initiation fees of the approximately 250,000 steel workers signed up during the campaign, not to speak of thousands of dollars in per capita tax from armies of dues payers over a period of many months, it is safe to say that their net outlay of $461,971.29 would be nearly if not altogether offset by their income. It is true that some of the organizations, like the Miners and the A. F. of L. itself made large expenditures, with little return; and that others, like the Structural Iron Workers, broke about even; while the Amalgamated Association put a huge sum in its treasury. All things considered, taking the twenty-four organizations as a whole, one is not much wrong in saying that so far as their national treasuries were concerned, the great movement of the steel workers, including the organizing campaign and the strike, was, financially speaking, just about self-sustaining.

Was the steel strike, then, worth the great suffering and expenditure of effort that it cost the steel workers? I say yes; even though it failed to accomplish the immediate objects it had in view. No strike is ever wholly lost. Even the least effective of them serve the most useful purpose of checking the employers’ exploitation. They are a protection to the workers’ standards of life. Better by far a losing fight than none at all. An unresisting working class would soon find itself on a rice diet. But the steel strike has done more than serve merely as a warning that the limit of exploitation has been reached; it has given the steel workers a confidence in their ability to organize and to fight effectively, which will eventually inspire them on to victory. This precious result alone is well worth all the hardships the strike cost them.

1. Exceptions to this were the cases of the Molders’ and Coopers’ Unions. These organizations were compelled by constitutional requirements to pay regular strike benefits. But they included only a very small percentage of the total number of strikers.

2. The commissariat was suggested by John Fitzpatrick, as a result of his experiences in the Chicago Garment Workers’ strike of a decade ago.

3. In addition to the regular commissaries, the local organizations, grace to their own funds or occasional donations from their international unions, had relief enterprises of various sorts, such as soup kitchens, milk, clothes, rent and sickness funds. In Monessen and Donora the strikers actually served a big turkey dinner on Thanksgiving Day. Strikers paid five cents a plate for all they wished to eat. Sympathizers donated liberally according to their means. But the commissary system was the main source of strike relief.

4. It is true, as noted above, that several other unions besides the Molders and Coopers made occasional contributions to their strike-bound locals, but when measured against the vast armies of strikers, these funds dwindled almost into insignificance.

5. This was largely because the men were sober. In fact, prohibition helped the steel campaign in several important respects; (1) because having no saloons to drown their troubles in, the workers, clear-headed, attended the union meetings and organized more readily; (2) when the strike came they did not waste their few pennies on liquor and then run back to work in the old way; they bought food with them and stayed on strike; (3) being sober, they were the better able to avoid useless violence and to conduct their strike effectively.

6. This sum represents the actual cash given by these affiliated organizations directly to the National Committee throughout the entire movement. It divides itself as follows:

| Total | $101,047.52 |

| Blacksmiths | $6,273.28 |

| Boilermakers | 10,448.92 |

| Bricklayers | 4,199.05 |

| P. & S. Iron Workers | 7,335.78 |

| Coopers | 907.76 |

| Electrical Workers | 6,138.80 |

| Engineers | 100.00 |

| Firemen | 2,395.53 |

| Foundry Employees | 1,030.51 |

| Hod Carriers | 1,350.00 |

| Iron, Steel and Tin Workers | 11,881.81 |

| Machinists | 16,622.33 |

| Mine, Mill, Smelter Workers | 3,583.53 |

| Mine Workers | 2,600.00 |

| Molders | 4,199.05 |

| Pattern Makers | 615.52 |

| Plumbers | 2,581.04 |

| Quarry Workers | 412.50 |

| Railway Carmen | 10,448.30 |

| Seamen | 3,081.04 |

| Switchmen | 4,115.52 |

| Sheet Metal Workers | 100.00 |

| Steam Shovelmen | 627.25 |