Ca

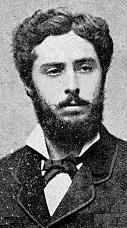

Cabet, Étienne (1788-1856)

French utopian, author of Voyage en Icarie.

Further Reading: Étienne Cabet Archive including excerpts from Voyage en Icarie

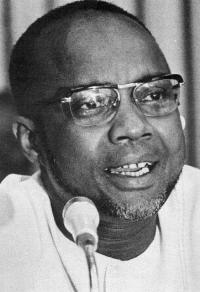

Cabral, Amilcar (1924-1973)

Architect and undisputed leader of the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC) -- the national liberation movement in Guinea-Bissau.

Architect and undisputed leader of the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC) -- the national liberation movement in Guinea-Bissau.

In the early 1950s, Cabral was employed as an Agronomist. Using this position, he went to every village in the entire country and from this direct observation, he came up with an analysis and strategy for the national liberation movement.

With others, he founded the PAIGC in 1956, and in 1963 their full-blown military campaign to overthrown Portuguese colonialism began. Within two years they had extensive liberated zones where effectively they were in power.

In 1971 Cabral argued for the creation of the National People’s Assembly, which was created in 1972 and based on popular vote in the liberated territories.

On 20 January 1973, just months before the victory of the national liberation struggle, Cabral was assassinated with the help of Portuguese agents operating within the PAIGC.

Further Reading: Amilcar Cabral Archive.

Cafiero, Carlo (1846-1892)

Italian Anarchist, published a condensed version of Capital in Italian.

Further Reading: Carlo Cafiero Archive.

Albizu Campos, Pedro (1891[93?] – 1965)

Born in Ponce, on the island’s southern coast, Don Pedro was the most uncompromising fighter for Puerto Rican independence of the 20th Century, spending two decades behind bars for his activities.

Though educated at the University of Vermont and Harvard, and having served in the US Army during World War I, Albizu Campos considered the US presence in his homeland not only a violation of his people’s right to self-determination, but a violation of the rights granted Puerto Rico by the Spanish prior to that country’s defeat by the US in 1898.

His nationalist activities began in earnest upon his return to Puerto Rico in 1921, and he was elected leader of the Partido Nacionalista de Puerto Rico. After the party abandoned electoral activity Albizu Campos was arrested on several occasions for advocating and organizing violent uprisings against the occupying power.

During his final incarceration, which lasted from 1954-1964, Don Pedro’s health deteriorated badly, which he claimed was a result of his being the guinea pig in unauthorized experiments on the use of radiation. These accusations have since been found to have basis in fact.

Further Reading: Pedro Campos Archive

Canne Meijer, Henk (1890-1962)

Dutch Council Communist and leading theoretician of the Group of International Communists of Holland (GIK) under whose auspices the Fundamental Principles of Communist Production and Distribution was first written and published. He is chiefly known for his theoretical work Das Werden der neuen Arbeiterbewegung, in which he advocated a struggle to replace the traditional reformist trades union movement, with its centralised structure of command and bureaucratic methods of organisation, by a system of autonomous industrial groups which would emerge into open activity only as and when issues of struggle arose within a particular establishment, and which then disappeared from public view - though not from clandestine activity - with the resolution, one way or the other, of the dispute which had given it birth. This important contribution on the debate on alternatives to reformist Social Democracy was published in Germany in 1936 by the General Workers' Union of Germany.

Further Reading: Henk Canne-Meijer Archive

Cannon, James P. (1890-1974)

Joined the Socialist Party in 1908, and three years later went over to the IWW, becoming a travelling organiser for the IWW, leading many strikes. After the Russian Revolution, he rejoined the SP, and aligned with John Reed’s faction to become a founding member of the CP in 1919, and was elected to the Central Committee in 1920. The CP had been a clandestine party, and Cannon was one of those advocating ‘coming up’ to be able to conduct mass work. This turn was carried out successfully, leading to Cannon being elected National Chairman of the ‘Workers Party’. This precipitated a split in the CP, and Cannon and his supporters were suspended by the majority who favoured continued illegality. Moscow intervened however, and supported Cannon’s policy. EC of CI in Moscow 1922-23, and headed International Labour Defence 1925-28, joined Left Opposition in 1928, and expelled. Founder, with Schachtman and Abern, of Communist League of America; led Trotskyist leadership of the Teamsters Union; founder of US Socialist Workers Party in January 1938. Participated in bitter factional struggle in 1940 against Burnham and Schachtman’s “petit-bourgeois opposition”, the subject of Trotsky’s In Defence of Marxism; Jailed 1944-45 for opposition to war; National Sec. of SWP till his death in August 1974.

Joined the Socialist Party in 1908, and three years later went over to the IWW, becoming a travelling organiser for the IWW, leading many strikes. After the Russian Revolution, he rejoined the SP, and aligned with John Reed’s faction to become a founding member of the CP in 1919, and was elected to the Central Committee in 1920. The CP had been a clandestine party, and Cannon was one of those advocating ‘coming up’ to be able to conduct mass work. This turn was carried out successfully, leading to Cannon being elected National Chairman of the ‘Workers Party’. This precipitated a split in the CP, and Cannon and his supporters were suspended by the majority who favoured continued illegality. Moscow intervened however, and supported Cannon’s policy. EC of CI in Moscow 1922-23, and headed International Labour Defence 1925-28, joined Left Opposition in 1928, and expelled. Founder, with Schachtman and Abern, of Communist League of America; led Trotskyist leadership of the Teamsters Union; founder of US Socialist Workers Party in January 1938. Participated in bitter factional struggle in 1940 against Burnham and Schachtman’s “petit-bourgeois opposition”, the subject of Trotsky’s In Defence of Marxism; Jailed 1944-45 for opposition to war; National Sec. of SWP till his death in August 1974.

Further Reading: James Cannon Archive

Campbell, John Ross (1894-1969)

Born in 1894, John Ross Campbell, always ‘J R’ in his published work, ‘Johnnie’ to his close comrades, was primarily a Communist journalist, with a bent to the Party’s industrial work. He was awarded the Military Medal in the First World War for his service in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. Along with Willie Gallagher, he was associated with the National Workers Committee, a syndicalist inspired workers organisation with close ties with the former Clyde Workers’ Committee. He was also a foundation member of the Party.

Born in 1894, John Ross Campbell, always ‘J R’ in his published work, ‘Johnnie’ to his close comrades, was primarily a Communist journalist, with a bent to the Party’s industrial work. He was awarded the Military Medal in the First World War for his service in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. Along with Willie Gallagher, he was associated with the National Workers Committee, a syndicalist inspired workers organisation with close ties with the former Clyde Workers’ Committee. He was also a foundation member of the Party.

He became notorious, following his arrest in 1924 for sedition. As acting editor of Workers Weekly, the Party paper, he had made an appeal in its columns to British troops. He was charged with inciting mutiny for his ‘Open letter to the fighting forces’—in which he called on soldiers and sailors to “turn your weapons on your oppressors”. The labour movement responded strongly to this attack on free speech, which merely sought the ‘neutrality’ in class struggle that the British state always claimed for itself.

The minority Labour Government, the first, then failed to proceed with the prosecution. To the fury of the press, the Labour attorney general had decided to prosecute the charge of sedition since there was a dearth of valid evidence. The campaign against Labour was sealed with the infamous Daily Mail forgery, the ‘Zinoviev’ letter. Both issues played some role in the excuse to overturn the government and force another general election after only nine months.

The Communist Party produced a pamphlet detailing Campbell’s defence in court entitled The Communist Party on Trial—J R Campbell’s Defence. Campbell was also arrested in the police raid on the Party’s headquarters in preparation for the General Strike.

He was an unsuccessful parliamentary candidate in 1929, 1945 (when he stood for the Party in Greenock), 1950 and 1951. He joined Harry Pollitt in concern about the Party line opposing the war against Germany from 1939 until the German invasion of Russia in 1941, and served on the executive committee of the CPGB. He became editor of the Daily Worker in 1949.

The National Archives contain extensive security service files on Campbell, only released in recent times. One security file includes speculation that when Campbell was appointed editor of the Daily Worker, John Gollan, was simultaneously made assistant editor to watch Campbell and make sure that he followed the party line. There are extensive reports of Campbell’s activities from as far back as 1920, including reports of speeches made, cuttings of his journalistic work and general surveillance material. A bundle of documents from the security forces show detailed observation from 1933 to 1953 for the activities of Campbell’s wife, Sarah. A reports on Campbell’s arrest for obstruction at a Communist Party meeting in February 1937 was also retained by the security forces.

He was editor of the Daily Worker in 1939, Assistant Editor from 1942-49 and Editor from 1949; he died in 1969.

From Graham Stevenson.

Further Reading: J. R. Campbell Archive.

Cantor, Georg (1845 - 1918)

German mathematician who founded modern Set Theory and introduced the concept of transfinite numbers, indefinitely large but distinct from one another. Cantor wrote little of a philosophical nature, but his startling achievements in fundamental investigations of mathematics stimulated the deeper enquiry into the epistemological foundations of mathematics which had a profound influence on Western thought during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

German mathematician who founded modern Set Theory and introduced the concept of transfinite numbers, indefinitely large but distinct from one another. Cantor wrote little of a philosophical nature, but his startling achievements in fundamental investigations of mathematics stimulated the deeper enquiry into the epistemological foundations of mathematics which had a profound influence on Western thought during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

Of prosperous and cultured Danish-born parents, Cantor’s talent for mathematics was observed when he was only 14 and by the age of 18 he was studying under the great mathematicians Karl Weierstrass and Leopold Kronecker, and by 1867 had published a doctoral thesis on one of Gauss’s famous unsolved problems. Cantor then joined the University of Halle, where he remained for the rest of his life.

In a series of papers published from 1869 to 1873, Cantor dealt with the theory of numbers, trigonometric series - in which he extended the concept of real numbers, Riemann’s complex numbers, and a new definition of irrational numbers in terms of convergent sequences of rational numbers. Following an exchange of letters with Dedekind, he then began the work for which he is famous: Set Theory and the concept of transfinite numbers.

In 1873, Cantor used the idea of one-to-one correspondence to show that the rational numbers (i.e. fractions), though infinite in number, are countable because they may be arranged in a one-to-one correspondence with the natural (whole) numbers, but, contrariwise, the set of real numbers (i.e. including numbers with infinitely many decimal digits) was uncountable. Even more paradoxically, he proved that the set of all algebraic numbers (such as the square root of 2 and so on) are as numerous as the natural numbers, but transcendental numbers (such as pi), which are a subset of the real numbers, are uncountable and therefore more numerous than the natural numbers!

The results were so startling that at first Kronecker refused to publish it.

Cantor’s theory quickly became controversial, leading to the study of a whole sequence of “transfinite numbers” each larger than the one before. Cantor held that these transfinite numbers had an actual existence, drawing on his early religious training to justify the assertion. Kronecker, on the other hand, famously remarked that only the integers ‘exist’ – “God made the integers, and all the rest is the work of man” – and blocked Cantor’s appointment to the University of Berlin.

Cantor continued work despite bouts of mental illness. Partly because of his experience with Kronecker, he often supported young, aspiring mathematicians. At the turn of the century, his work was fully recognised as fundamental to the development of function theory, analysis and topology. Moreover, his work stimulated further development of both the intuitionist (Brouwer) and the formalist (Hilbert) schools of thought in the logical foundations of mathematics.

Cardenas, Lazaro (1895-1970)

Mexican army officer and politician, president 1934-1940. His was the only government in the world that would give Trotsky asylum in the last years of his life. In 1938 he nationalised the operations of the foreign oil companies in Mexico.

Carey, Henry Charles (1793-1879)

American economist who theorized against Malthus and Ricardo. His work was praised by Marx.

Carlson, Grace (1906-92)

Joined the Workers Party of the United States, the predecessor of the Socialist Workers Party, in 1936. She was elected to the SWP national committee in 1941, was indicted in the Minneapolis sedition trial and jailed, and stood for vice-president in the SWP’s first presidential campaign in1948. Broken by the witch-hunt, in 1952 she left the party to return to the Catholic church.

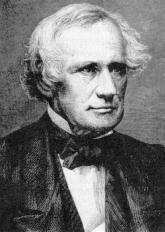

Carlyle, Thomas (1795-1881)

The leading British disciple of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and German Romanticism. He was also, in his youth, a supporter of Saint-Simonism and the Chartist movement. However,

in later life, the positions he took on political and economic affairs seemed

more in line with the Tories.

The leading British disciple of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and German Romanticism. He was also, in his youth, a supporter of Saint-Simonism and the Chartist movement. However,

in later life, the positions he took on political and economic affairs seemed

more in line with the Tories.

Carlyle is renowned for his passionate, preacher-like opposition to industrial society that was emerging in Britain, captured in his Chartism (1840) and, especially, Past and Present (1843), a book much admired by Engels. Carlyle was not an economist or even a scholar, but more like an Old Testament prophet. His utter disdain for economists and economics is well known – it was he who characterized it as “the dismal science.” In his view, it was the economists and their theories which served as the apologistic ideological and religious buttress of the industrial revolution that, in his view, was destroying Britain. At one point, he recommended that economists ought to be “popularly elected” as a way to make them accountable to the population that their theories were helping ruin. Nonetheless, he was, at least for a time, a friend of John Stuart Mill. He was also a close friend of John Ruskin.

Thomas Carlyle was a “feudalist” (if such a term can be allowed). But he does not pine for old-fashioned reactionary aristocracy or pastoral romance. Rather, Carlyle absorbed Goethe’s ideas on the “natural,” in particular the relationship between external order and personal freedom. He conceived that the end of human activity is activity itself – the Protestant ethic, secularly enhanced.

For Carlyle, the feudal system’s sole value is that it is much better at assigning a man an activity and thereafter granting him the freedom to pursue it in any manner he pleases. In contrast, a market system assigns him no activity, but simultaneously becomes the hardest taskmaster of all by forcing him to “serve it” by chasing wage labor, profit, etc. He sees a market society as “unnatural” as it forces people to pursue consumption and accumulation, whereas, in Carlyle’s view, people’s nature is to pursue activity.

Thus, for Carlyle, the feudal system may be harsh in limiting social mobility, but it offers freedom of activity at the individual level and the joy of craftsmanship. In contrast, the market system is socially much more progressive, but at the individual level, it forces everybody into the unnatural activities of gain and acquisition.

Carlyle’s darkest moment was the publication of his infamous defense of slavery (in his 1849 Fraser’s Magazine) and his shamelessly racist and venomous Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850).

Carlyle saw little difference between a black slave in a slave society and a joyous yeoman in a feudal society– except that one is loyally bound to his task by chains and whips, and the other by tradition and custom. In either case, the “joy of work” is (eventually) achieved.

It was his attacks on the Evangelical Christian abolitionism and charity which were the main sore point with Victorian society.

But neither a feudal society nor a slave society are being “recommended” by Carlyle. His early interest in Saint-Simonism, which embraced industrial society (but tried to rationalize it) proves that he was not a traditional feudalist. The main issue was the “man-must-work” principle of Saint-Simon and Goethe. How this can be achieved in an industrial society, he did not know nor did he have practical policy suggestions for. He was a man of letters. He wrote to shock.

Carnap, Rudolph (1891 - 1970)

German-born Logical Positivist philosopher. He contributed to logic, the analysis of language, the theory of probability and the philosophy of science; typical of the third stage of positivism, “Neo-Positivism”, Carnap’s method is a kind of systematic reductionism, in which language and concepts are seen as a hierarchy of “short-hands”, at the end of which are individual sensuous impressions – a fairly shallow attempt to justify the place of mathematical logic in a broader domain than it is usually found useful.

Carnap studied mathematics, physics, and philosophy at the University of Jena where he attended Gottlob Frege’s lectures, which exerted a deep influence on him.

After serving in World War I, Carnap did his PhD at Jena on the concept of space, which he held to conflate several quite distinct meanings: formal space, physical space, and intuitive space. Subsequently, his work centred on symbolic logic and the foundations of physics.

In 1926 Moritz Schlick, the founder of the Vienna Circle, invited Carnap to join the University of Vienna, where he soon became an influential member of the Circle. Out of their discussions developed the initial ideas of Logical Positivism, or Logical Empiricism. This school shared its basic Empiricist and sceptical orientation with David Hume and Ernst Mach. Carnap brought to this group the techniques of Frege’s symbolic logic which he held to be superior to the discursive methods of traditional logic. Carnap also formed an assocation with Hans Reichenbach in Berlin, and together they published the periodical, Erkenntnis.

For Carnap, the problem of knowledge reduced to a logical analysis of the evidential basis for statements about the world on the basis of immediately given sense-data. No thought was given to the active character of sensuousness or the problem of the origin of the categories through which the data of the senses may be comprehended, and Carnap regarded logic and mathematics to be subject to a priori verification, since they did not rely on empirical observation.

In his philosophical work, The Logical Structure of the World: Pseudoproblems in Philosophy published in 1928, Carnap developed a reductive schema through which all terms suited to describe empirical facts are definable in terms referring exclusively to elements of immediate experience.

Under pressure of critique by his Vienna Circle colleagues, Carnap modified his schema to utilise the concept of “Reduction Sentences” – much-refined versions of operational definitions, and “Observation Sentences” – whose truth can be checked by direct observation. He presented his new position in the essay Testability and Meaning in 1937. Carnap now argued that the terms of empirical science are not fully definable in purely experiential terms, but that statements that cannot be tested by observational findings were meaningless.

By the time Testability and Meaning appeared, Carnap had moved to the University of Chicago to escape the Nazi invasion. During 1940-41, Carnap was a visiting professor at Harvard University and an active participant in a discussion group that included Bertrand Russell, Alfred Tarski, and Willard Quine.

Carnap spent his last years at Princeton, where worked on probability theory, and continued to modify his system of inductive logic.

See Philosophical Foundations of Physics.

Carpenter, Edward (1844-1929)

British socialist, writer and poet. Carpenter’s early interest in religion led him to become an ordained deacon in 1870, and later curate at St. Edward’s Church, Cambridge.

British socialist, writer and poet. Carpenter’s early interest in religion led him to become an ordained deacon in 1870, and later curate at St. Edward’s Church, Cambridge.

In 1882 an inheritance from his father left him financially independent. He bought a small farm near Sheffield, became a self-sufficient grower and became involved with the local socialists and radicals. In 1898, Carpenter and George Merrill began a thirty year union.

Carpenter was influenced by, among others, William Morris and in 1885 joined him, Eleanor Marx, and Edward Aveling in the Socialist League.

In 1893 Carpenter joined with Keir Hardie, George Bernard Shaw, Philip Snowden, and Ramsay Macdonald and others to form the Independent Labour Party.

In 1986 Carpenter published his book, Love’s Coming of Age, a controversial book that dealt both with the subjects of sexual liberation for homosexuals and women in 1914, he was a founder of the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology.

Some of his works: England’s Ideal, 1885; From Adam’s Peak to Elephanta, 1892; A Visit to a Gnani; Homogenic Love, 1895; Love’s Coming of Age, 1896; The Art of Creation, 1904; The Intermediate Sex, 1908; and his autobiography, My Days and Dreams, 1916.

Further Reading: Edward Carpenter Archive.

Castro, Fidel (1927-2016)

Born in Cuba, lawyer; led armed attack on Moncada barracks 26 July 1953, freed after 2 years in prison, and went to Mexico where he prepared a guerrilla force to overthrow Batista. Landed in Cuba in December 1956 with 80 supporters under a barrage of helicopter gunfire; where only 12 members of the landing party survived; among them was the Argentinian Doctor, Che Guevara. Through enourmous struggle, Castro led a successful guerrilla campaign from the countryside, based on the strong support of the Cuban farm workers. In January 1959, the guerillas marched into Havana as victors in the war.

Born in Cuba, lawyer; led armed attack on Moncada barracks 26 July 1953, freed after 2 years in prison, and went to Mexico where he prepared a guerrilla force to overthrow Batista. Landed in Cuba in December 1956 with 80 supporters under a barrage of helicopter gunfire; where only 12 members of the landing party survived; among them was the Argentinian Doctor, Che Guevara. Through enourmous struggle, Castro led a successful guerrilla campaign from the countryside, based on the strong support of the Cuban farm workers. In January 1959, the guerillas marched into Havana as victors in the war.

Immediately after coming to power, the government attempted to secure trade ties with the US, its principle economic trading partner. These talks failed when Nixon (then the vice president), suspected that Castro was a Communist. On this suspicion, before Castro or the Cuban government declared itself Socialist, Eisenhower began planning the U.S. invasion at the Bay of Pigs, which was later carried out by John Kennedy. Meeting fierce opposition from the Cuban people, the US ‘Bay of Pigs’ invasion failed dismally. The U.S. government took another approach: kill Castro any way possible. The CIA stopped at nothing, and failed at everything, from posioning food, cigars, his clothing, to dropping bombs, hiring gunmen to shoot him dead, to working with the Mafia to blow up his car. They were such extreme failures when so many would be assassins defected, so many informants turned sides, that the CIA began trying entirely ridiculous plots to downplay their assassination attempts: from poisoning his wet suit to planting drugs that would make his beard fall out. (Further Reading off-site: CIA Operation Mongoose)

With U.S. assassination attempts on his life, constant U.S. terrorism (bombing factories, setting sugar cane on fire with napalm, etc), and economic embargo, Castro turned for support to the USSR, leading to the 1962 Cuban missile Crisis. Castro took over the Cuban Communist Party, changing the name of the party to the ‘Communist Party’ in 1965. With Che Guevara, Castro supported national liberation struggles in the third world, most notably in Angola, the Congo, Libya, and Bolivia. Castro publicly supported the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. Supported Gorbachev’s glasnost policy and ‘new thinking’ in international policy. In the 1990s, facing extreme economic disaster due to the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, Castro allowed Western capitalists to conduct limited business in Cuba so that Cuba could survive, still under economic, military, and political embargo from the most powerful nation in the world. Castro never renounced his internationalist socialist ideology.

Further Reading: Fidel Castro Archive

Cato, Marcus (95-46 B.C.)

Roman statesman, head of the aristrocratic Republican Party

Caudwell, Christopher (1907-37)

Christopher Caudwell was the pen-name of Christopher St. John Sprigg, born into a Catholic London family. He started working as a journalist at the age of fifteen. He was soon to become editor of British Malaya. Later on he started running an aeronautics publishing company together with his brother. In addition he wrote poetry, plays, short stories, detective novels, aeronautics textbooks and ghost stories. Also at the same time he read voluminously in philosophy, sociology, history, politics, linguistics, mathematics, economics, physics, biology, neurology, literature, literary criticism and so on.

Christopher Caudwell was the pen-name of Christopher St. John Sprigg, born into a Catholic London family. He started working as a journalist at the age of fifteen. He was soon to become editor of British Malaya. Later on he started running an aeronautics publishing company together with his brother. In addition he wrote poetry, plays, short stories, detective novels, aeronautics textbooks and ghost stories. Also at the same time he read voluminously in philosophy, sociology, history, politics, linguistics, mathematics, economics, physics, biology, neurology, literature, literary criticism and so on.

In 1934, he developed a special interest in Marxism, and in the summer of 1935 he wrote Illusion and Reality, a Marxist critique of poetry. After finishing the book he joined the Communist Party, and soon became a dedicated grassroots activist, still continuing his writing, even though none of his works were printed during his lifetime.

In December 1936, he left for Spain to join the International Brigades in the anti-fascist struggle against Franco. He soon became a machinegun instructor and editor of the Battalion Wall newspaper. Christopher Caudwell was killed by the fascists in the valley of Jarama February 12th 1937, during his first day of battle. He was last seen firing a machinegun, covering the retreat of his section from a hill about to be taken by the Moors.

Further Reading: Christopher Caudwell Archive

Cayan, Mahir (1945-1972)

The founder of the People Liberation Party-Front of Turkey (THKP-C).

The founder of the People Liberation Party-Front of Turkey (THKP-C).

He entered in 1964 to the Faculty of the Political Sciences of the Ankara University. He joined the Workers Party of Turkey (TIP) and the Federation of the Clubs of Ideas (FKF) (Later, Revolutionary Youth, Dev-Genç). He led a lot of demonstrations against NATO and US imperialism. Under the direct effect of the Cuban Revolution he advocated in the TIP the thesis of "National Democratic Revolution". He found the THKP in 1971 and periodical "Kurtulus" and organised some Urban Guerilla Actions. After the military putsch in March 1971 THKP kidnapped the Consulate General of Israel, Ephrahim Elrom. In 1972 to prevent the execution of Deniz Gezmis and friends, Çayan and the leader cadres of the Party kidnapped three British technicians who worked at a military centre. They were soon killed by Turkish soldiers at 30 March 1972 in Kizildere.

Further Reading: Mahir Çayan Archive